[Updated on 5/9/17]

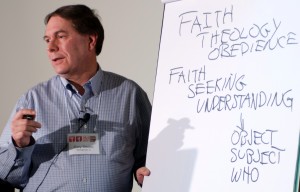

For over 20 years, GCI has embraced and strongly emphasized a biblical, Christ-centered and historically orthodox understanding of the covenant, the law and God’s faithfulness. In this essay, Dr. Gary Deddo both summarizes and clarifies that understanding.

Introduction

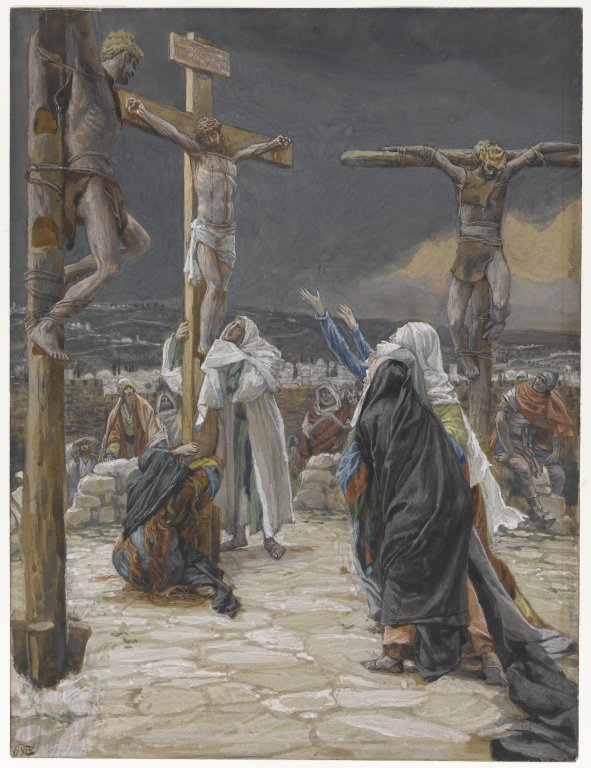

Central to GCI’s reformation is the teaching that the covenant was fulfilled in Jesus Christ on our behalf. By looking back from the vantage point of Jesus’ declaration on the cross, “It is finished,” we are able to understand not only what God was doing with Israel via the covenant (to which was added the Mosaic law), but also God’s related plan for all humanity that reaches back “before the creation of the world” (Ephesians 1:4). This essay elaborates on these important, related topics, expanding on what Joseph Tkach addresses in his articles in the March 22 Weekly Update and in this issue.

(public domain via Wikimedia Commons)

Seeking understanding

Down through church history, there have been different understandings concerning God’s covenant with humanity, particularly the relationship between what is commonly referred to as the old covenant and the new covenant. These understandings have shifted through the centuries, ranging from making little distinction between the old and new covenants (though typically giving prominence to one or the other), to making radical distinction—one so great that it implies God had two very different, even incompatible, purposes; or even that there is a different god behind each covenant (a heresy, called Marcionism, which arose in the early church).

How does GCI understand the points of similarity (continuity) and difference (discontinuity) between the covenants, and how do we sort out the various issues related to God’s covenant with his people? In this essay, we’ll seek to answer these questions, providing a theological synthesis that, hopefully, will point us faithfully to the truth and reality of who God is and who we are in covenant relationship to him—a reality revealed fully and finally in Jesus Christ. As we arrive at that synthesis, we will seek to take into account the whole testimony of Scripture related to these points, and we’ll borrow from the best of what others before us have contributed to the task.

The “old” and “new” covenants

English translations of the New Testament speak several times of a “new covenant” and an “old covenant.” But in the original Greek, there is only one reference to an “old” (παλαιας, palaias) covenant—that verse is 2 Cor. 3:14. In this context, a contrast is being made between the dispensation of the Spirit (who writes on “tablets of human hearts”) and the dispensation of the law (written on “tablets of stone”)—see 2 Cor. 3:3. The addition in English translations of the word “old” in other verses leads to the false impression that there is an almost total disconnection between the old and new covenants. While there are important points of distinction, there is not total disconnection, as we’ll see.

The places where “old” is added to the Greek text in some of the English translations are 2 Cor. 3:6; Heb. 8:6, 13; 10:9, 11. This addition is an attempt to enhance the contrast that is being made. However, the contrast being made in the Greek text of these verses is other than old/new. The contrasts there are what gives life not kills and what is “better” between first and second. Multiplying the instances of the word “old” is thus misleading, detracting from the actual contrasts that are being made—namely contrasts between what came first and what came second.

When Scripture makes use of this old/new contrast, should we think of it as absolute?—as in “absolutely old in every conceivable way” and “absolutely new in every conceivable way”? Or should the contrast be understood as indicating a relative difference? The only way to answer that question is to consider all that is revealed about God’s relating to his people down through time and, if we are told, about God’s intentions before time began (before creation). Without questioning the radical disconnection (discontinuity) between the covenants, is there still some connection (continuity) that the biblical revelation points to and to which we can refer with appropriate words?

Old and new not dichotomous

When we look into the meanings of the words translated “old” and “new” in the New Testament, it becomes apparent that these are not dichotomously opposed terms, which are to be understood in an absolute way. The covenant made or fulfilled in Christ and by the Spirit is called “new” seven times—six using the Greek word kainēs (καινης) and once by another Greek word close in meaning (νεας, neas)—see Luke 22:20; 1 Cor. 11:25; 2 Cor. 3:6; Heb. 8:8, 13; 9:15; 12:24.

“New” does not usually, if ever, mean absolutely new, having nothing preceding it, or absolutely no connection with what has gone previously. Kainē means new in quality (not kind), a fresh development, recently made, fresh, unused, superior to what it succeeds. We can see this in Jesus saying he was giving a “new” command (John 13:34). The command to love was not absolutely new (see Lev. 19:18). What is new is not something that begins from absolutely nothing. Though there is room in the meaning of “new” for some continuity with what came before, there is obviously significant change as well.

When speaking of the covenant, the idea of old means old in age, ancient, antique or no longer new, worn by use, the worse for wear, worn out, of no more use. Old then does not mean of a completely different kind of thing (compared to what is new), or opposed in kind or unrelated to what is new, or that it had no value.

Some English translations of Hebrews 8:13 (KJV) use the word old to describe the covenant—covenant being implied from previous verses Heb. 8:9, 10. But the particular word, pepalaioken (πεπαλαιωκεν,) is not exactly the same word used in 2 Cor. 3:14. This word is better translated “has become obsolete.” It means “outdated” because it is worn out or no longer of use. Another word used to translate it, “abrogated,” is borrowed from western legal language meaning one law is being superseded by another. In contrast to the covenant that is “new” and “first,” what is obsolete is also described in this compact verse as “growing old,” (παλαιουμενον, palaioumenon), “aging” (γηρασκον, geraskon) and “near vanishing.” (εγγυς αφανισμοσ, engys aphanismou). Closely related words are used in Hebrews 7:18 (ESV) to describe the commands regarding the Levitical priesthood being “weak” and “useless” or becoming “unprofitable.”

What is old, then, is not an enemy of what is new—it is not a threat or in opposition to what is coming. It does not have an opposite nature compared to what is new. But what is old has come to a point of no longer being useful and so is to be “set aside” (2 Cor. 3:11 NRSV) so that the new can take over from that point forward. The old is to be left behind and so “vanish away.” The new takes up where the old leaves off. There is not complete discontinuity indicated in this contrast. The difference between old and new is relative, not absolute.

First and second, first and new, better, eternal

A significantly more prominent way that what is “old” is distinguished from God’s “new” covenant purposes accomplished in Christ, is by indicating their order—naming one “first” and the other “second.” The author of Hebrews addresses the covenant idea more than any other New Testament book. In doing so, he does not use the idea of old itself but gives prominence to other contrasts such as between first and second, first and new, or to what is “better.” Two passages make the first/second contrast (Heb. 8:7 ESV and Heb. 10:9 ESV), and another speaks of the first covenant and thereby implies a second (Heb. 8:13). This contrast indicates a distinction of two things ordered in a sequence.

The first/second distinction does not of itself indicate a disjunction, opposition or complete independence of one from the other. It also does not indicate that what is “first” is absolutely first, just that it is first in order (sequence) as compared to what is identified as “second.” That one is said to be first and another second also suggests a certain continuity between the two. However, there is also a suggestion of discontinuity, with the second taking over where the first left off. The difference between what is first in time (old) and what is second in time (new) is not absolute—the difference is relative, but still involves significant discontinuity even if that discontinuity is not absolute. This contrast seems to indicate a very significant development—perhaps a kind of quantum leap (to speak in our contemporary vernacular).

The author of Hebrews also speaks of a first/new contrast in Heb. 9:15 and also in Heb. 8:13 (ESV), in addition to the first/second contrast in that same verse. Also prominent in this author’s mind is that what comes second or is new is “better,” meaning more useful, more serviceable, most excellent. “Better” appears 12 times in Hebrews—twice in relationship to the ministry of Jesus (Heb. 7:22; 8:6 ESV). Note also that Hebrews declares that Christ’s blood poured out for us has established an “eternal covenant” (Heb. 13:20 ESV).

Taking into account all these various contrasts regarding the covenant, it is apparent that a simple old/new pattern does not tell us everything we need to know about God’s relationship between his people before and after Christ. It should now be apparent that the relationship is not one of being entirely discontinuous or in opposition, although the relationship does involve significant distinction or development.

Both are covenants

The second thing to note is that the word, “covenant,” which is used in each case, is then qualified by the two descriptors: old and new. If what is meant are two entirely separate things, then why even use the same word (covenant)? Why not call one a covenant and identify the other relationship by another term altogether? The fact that the same word is used in both cases, though qualified by two contrasting words, old and new, or first and second, is perhaps itself an indication that there is a connection between them—some kind of continuity. They are both covenants, though much more must be considered before we can draw definite conclusions.

(public domain via Wikimedia Commons)

Covenant distinguished from law

Why are both the old and new called covenants? What is a covenant? At this point it may be helpful to clear some ground. Often the ideas of the old covenant (διαθηκη) and the law (νομος) are thought to be synonymous, referring to the exact same thing. They came to be closely related and were inseparable in the life of Israel after Moses received the tablets of the law (the Torah). Although inseparable after that point in Israel’s history, they were and should still be distinguished, especially as we look back from our now being in Christ. The idea of covenant established with Abraham can include the law once given to Moses, but it can also refer to itself independently. The Mosaic law can be called a covenant. That’s because covenant and law are closely associated in Israel once given. But the Abrahamic covenant cannot be reduced to the law and the law, while included in the covenant after the law was given to Israel through Moses, is not identical to the covenant. This distinction is very important, even decisive.

The apostle Paul indicates this clear distinction by noting that the covenant came first, with Abraham. The law was “added” 430 years later! He puts it this way: “My point is this: the law, which came four hundred thirty years later, does not annul a covenant previously ratified by God, so as to nullify the promise (Gal. 3:17 NRSV). The law was thus added to the covenant (Gal. 3:19; Rom. 5:20). The covenant was not added to the law. The covenant has priority and so is not annulled by what is added. And that fact is key for Paul in helping his audience understand what God was doing in Israel and what he had done in Jesus. Covenant and the law can be and should be distinguished. What is true of the covenant may not hold for the law, at least in the same way. When we conflate the two words it becomes much harder to see the proper connection between the old (first) covenant and the new (second) covenant. Theologies that regard law and covenant as identical have tended to make more absolute the distinctions between the old and new covenants. However, Paul does not do that—instead he sets forth the priority of the Abrahamic covenant over the Mosaic Law, and so should we.

So what is a covenant, as distinguished from the law given to Israel through Moses? The answer is that a covenant is fundamentally a promise, a vow. In the case of God with human beings, it is a promise or oath that is unilateral—it is freely-given and established by God. The connection between covenant and promise can be seen in those many instances, in both the Old and New Testaments, when used in tandem or synonymously as in Psalm 105:9 (ESV): “The covenant that he made with Abraham, his sworn promise to Isaac.” A covenant can also be considered a “vow” or an “oath.”

It’s important to note that a covenant (berith in Hebrew) in Israel’s history with God, is not a bilateral contract (unlike modern definitions of the word covenant). Unfortunately, some modern English translations of the Bible imply that a covenant is a contract—binding on two parties who agree on mutual terms of obligation. This includes the idea that if one party fails to fulfill their part of the covenant-as-contract, then the entire arrangement and relationship is cancelled. But in Old Testament Hebrew, a covenant can be unilateral, an agreement made by one of the parties to it, namely by God. And it can be unconditional, that is, not require conditions to be met by the other party for the covenant to be established and remain in force. God’s words to Abraham reflect this meaning: “I will establish my covenant between me and you, and your offspring after you throughout their generations, for an everlasting covenant, to be God to you and to your offspring after you” (Gen. 17:7).

At the time of the New Testament, there were two Greek words that could be translated “covenant.” But one, diatheke, means a unilateral covenant, and the other syntheke means a bilateral covenant. The New Testament consistently uses diatheke to speak of God’s covenant with Israel and with his church. This is a covenant that is unilateral and unconditional. Notice that the Abrahamic covenant has no “if-then” clauses—it stands as a unilateral promise given by God.

Understanding this is somewhat complicated by the fact that the Mosaic covenant or law was added to the Abrahamic covenant. As given to Israel at Sinai, it included “if-then” clauses. This is known as case law. Such law specifies the conditions upon which a particular punishment is to be administered. So if Israel persistently disobeyed God they would be sent into exile. However, such conditions did not affect the existence of the covenant—they were merely ways in which the law was administered within the Abrahamic covenant. The existence of the covenant or persistence of God’s covenant purposes were not conditioned by what Israel did or did not do. However, the operation of the Mosaic law within the Abrahamic covenant did contemplate certain consequences based on Israel’s conformity or non-conformity to the stipulations of the laws with their blessings and curses. On this point, a comparison has been made to the difference between constitutional law, which applies to all citizens whether they break civil or case laws or not. The constitution remains valid and they remain citizens who have constitutional rights. The Abrahamic covenant is more like constitutional law than case law.

We are told that the Mosaic law was “added” to help Israel, in particular, know how more particularly to respond and live within God’s covenant purposes. Disobedience to the Mosaic law once given means resisting God’s covenant purposes for Israel as spelled out in the Abrahamic covenant, and so the consequences for their disobedience are spelled out. For example Moses was prevented from crossing over into the Promised Land due to his disobedience. But even Israel’s “breaking” of the law and so of the covenant did not condition God to annul his covenant promise to them. Though Israel was unfaithful, God remained faithful. The entire book of Hosea is a living parable of this radical truth. It is Mosaic law within the enduring Abrahamic covenant that stipulates conditions and consequences, not the more foundational and enduring unilateral and unconditional covenant or promise.

Given these factors, it is best that we use the word “contract” rather than “covenant” in referring to bilateral agreements between two parties with mutually obligating conditions. This becomes even more important because over time in much biblical and theological discourse, the distinction between a unilateral covenant and a bilateral contract (covenant) was blurred so that the unilateral and unconditional aspects of God’s covenant were lost. Because covenant and contract were used interchangeably (with the idea of contract becoming dominant and controlling) the idea of a unilateral and unconditional covenant was often lost. Making this distinction between covenant and contract is also complicated by the fact that Hebrew (unlike Greek) had only one word for both types of arrangements. For example, ancient empires often had a berith with each vassal nation that specified duties like a contract (see appendix 1 of the GCI article at https://www.gci.org/law/covenants). Another complication arose because Latin, the language of medieval and post-Reformation theology, also only had one word (foedus) for covenant and contract.

It also is important in making these distinctions to bring the idea of promise into close connection with covenant since we have a much easier time thinking of a promise being unilateral and unconditional compared to thinking of a covenant that way (since we assume most of the time that a covenant is the same thing as a contract, even when thinking of God’s unilateral covenant). And that connection is actually the most prominent and consistent way to think about the covenants especially as found in the New Testament where God’s covenant is essentially regarded as a promise.

God’s covenant promise to his people

The covenant as promise is most comprehensively summed up in the Old Testament and confirmed in the New Testament in these ways: “I will be your God and you will be my people,” or “you will be holy.” This exact refrain occurs seven times in the Old Testament, which then six more times simply states : “[I will] be your God.” These declarations occur at key points in God’s relationship with Israel (Ex. 6:7; Lev. 11:45; Lev. 22:33; Lev. 25:38; Lev. 26:12; Num. 15:41; Deut. 26:17; Deut. 29:13; Jer. 7:23; Jer. 11:4; Jer. 30:22; Ezek. 36:28). This is the most succinct form of God’s covenant, promise, vow or oath. Similar phrasing is found in Gen. 17:7 (NRSV): “I will establish my covenant between me and you, and your offspring after you throughout their generations, for an everlasting covenant, to be God to you and to your offspring after you.” This is a statement of relationship, with a similar formula being used to speak of marriages and adoptions, although these are bi-lateral covenants, in Greek a syntheke, not a diatheke. God’s covenant of promise is eternal or everlasting (Gen. 9:16; 17:7, 13, 19) and continues from generation to generation to the offspring of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob (Gen. 9:12; 15:18; 17:7, 17; Ex. 2:24; Lev 26:42; Deut. 29:13; 2 Kings 13:23).

Following Paul’s insight, we will eventually need to say something about the “law” being added, but for now we can definitively say God first formed his people around this unilateral covenant or promise with Abraham. With that covenant God established the essential shape or foundation of his relationship with his people. Such a freely-given and undeserved relationship of blessing is an act of grace. Such a promise was not earned. These people did not do anything to obligate God to offer such a covenant/promise. They did not condition God to set up such a relationship. God’s making of a covenant relationship is an act of his freely given grace. In that sense it is unconditional (the related party doesn’t fulfill conditions that make God obligated to them—that is, it is not what we regard as a contract). So whatever the law is that comes 430 years later, and for whatever reasons it is given, it occurs within and on the basis of God’s covenant relationship of promise with Israel already established! As already noted, it is not annulled by the law that is added. The covenant as promise is more fundamental, foundational and, as it turns out, enduring.

Promise calls for response

Although ordinances and statutes are not always specified, note that this covenant of grace (this promise made by God to his chosen people) calls for a response. The giver of the promise (God in this case) wants the recipient to believe that the promised blessings will be given. They are told to “keep the covenant” (Gen. 17:9, 10). Thus God’s unilateral promise (and not commands or law) calls for a response.

That God is their God calls forth from God’s people the response of being holy as God is holy (Lev. 11:45; 1 Pet. 1:15-16). James Torrance referred to this as the “unconditional obligations of grace.” Such obligations are not conditions of grace, but they are the way we receive and live in God’s free grace and so fully benefit from it. God’s covenant unilaterally and unconditionally creates a relationship with others—a relationship of grace. Given that it is a real relationship that is dynamic and personal, the unilateral covenant involves interaction, communication and communion. It is not mechanical, causal, impersonal or automatic.

Promise based on God’s covenant love (hesed)

If we ask why God establishes such a covenantal relationship with his people, the only answer we can give is God’s love—his special, unique kind of love, freely given and established through his covenant. That love is primarily designated in the Old Testament as hesed (or chesed). This word for love in some translations is rendered God’s “covenant love.” Often it is translated “everlasting” or “steadfast love.” This word, used to describe God’s unique relationship with Israel, is repeated many times throughout the Old Testament, reaching a crescendo in Psalm 136, which makes it a refrain 13 verses in a row: “His steadfast love endures forever”! (ESV translation). God’s covenant establishes a relationship of love as a promise.

Promise calls for the response of faith

What kind of response is Israel then obligated to make to God’s promise that, because he loves them, he will be their God and they will be his people? The most fundamental response called for is faith and faithfulness. Israel is to trust in God alone as their God, and so be faithful to him. When they fail to do so, they are called to turn to God for forgiveness, which he supplies. That is, they are to confess their sin and repent and receive God’s forgiveness. What can be seen throughout the Old Testament is that faith or belief is the response God calls for to his covenant love for and his relationship of grace with his people. Their primary disobedience is one of unbelief or distrust in God and so in his word of promise. Unbelief in the promise of God is disobedience; it is a failure to walk in the relationship that has been graciously given. Every other aspect of Israel’s relationship with God is to be lived out on the basis of God’s covenant love for them, which calls for their answer of faith and faithfulness, and repentance. That is the essence of their being God’s people.

Faith in God’s faithfulness

Now, hopefully, the link between the old covenant and the new covenant is becoming clearer. That link is God! God is the same God! God is the covenant God in relationship to Israel and in relationship to those in Jesus Christ, his church. And that relationship is one of freely-given grace, which is to be received, lived in, and lived out as his people. God is interested in setting up one kind of relationship with his people: a relationship of worshipping trust that is established in his grace, in his love. God himself is the continuity. God is a faithful covenant-making God. Period! God’s character is one and the same in both the old and new covenants and so is his will and purpose.

That is why this God always intended to have a “people for his name”—a people who would respond to and so live by and in his covenant love and grace—a people who would count on or believe or trust in his faithfulness! God’s intention is the same under both the old and new covenants. He establishes a people who know him and who receive his grace and love and who live out of trust in his faithfulness. God is interested in having only one kind of relationship with his creatures, not multiple kinds with different characteristics.

Continuity of a people

Another point of continuity is that God’s covenant forms a people, calls out a people to be in relationship with him. The church in the New Testament is designated “the called out ones” or “the ones called together in assembly” (ekklesia in Greek). So there is a continuity of God’s people under the two covenants. That is why Paul can say that the church is “the Israel of God” (Gal. 6:16) and that the Gentiles are being grafted into the root of Israel (Rom 11:17-18). That is also why Abraham can be designated the father of faith and why the followers of Jesus alone are designated the true children of Abraham. It also makes sense of Paul saying that the gospel was preached to Abraham: “And the scripture, foreseeing that God would justify the Gentiles by faith, declared the gospel beforehand to Abraham, saying, ‘All the Gentiles shall be blessed in you.’ For this reason, those who believe are blessed with Abraham who believed” (Gal. 3:8 ESV).

A promise looks towards future fulfillment

Since the old Abrahamic covenant is fundamentally a vow or oath and a promise, we should ask, what exactly is involved in the promise? A promise holds out something for the future, a hope. It means that more is coming. A promise is given in the present and even held in the present, but it looks to the future at the same time. So the idea of God’s being their God and his having a people involves both a present and an anticipated future. As a promise, the old covenant is admittedly incomplete. God is not yet fully their God, at least in that those to whom he has made the promise are not yet fully or completely worshipping him, or being the perfectly holy people he wants them to be as the goal of the covenant relationship. Other things must take place before the promise can be fully realized, or, as we more usually state it, before the promise is fulfilled, or “comes to pass.” The old or first covenant looked forward to a future fulfillment, worked out by God, the one who promised it would be.

The covenant promise to be fulfilled intensively and extensively

What did those who lived under the old Abrahamic covenant learn about the anticipated fulfillment of that covenant or promise? The covenant promise to be their God and for them to be his people was, by the prophets, spelled out more fully to involve two further expansions. God would write his laws/ways upon their hearts and even give them new hearts. This was pronounced by Jeremiah: “For this is the covenant that I will make with the house of Israel after those days, says the LORD: I will put my law within them, and I will write it on their hearts; and I will be their God, and they shall be my people” (Jer. 31:33 ESV). In the New Testament, this promise is proclaimed as fulfilled—especially in the book of Hebrews where these words are quoted twice (Heb. 8:6; 10:16). This fulfillment involves an intensification, a deepening of God’s work within individuals. It reaches their very hearts. The covenant would be intensified and reach far more deeply into their lives in the future.

But there is yet another aspect of fulfillment also anticipated in Israel, namely, that the blessing of Israel’s relationship with God would one day be extended. As the prophet Joel proclaimed, “And is shall come to pass afterward, that I will pour out my Spirit on all flesh; your sons and your daughters shall prophesy, your old men shall dream dreams, and your young men shall see visions. Even on the male and female slaves, in those days, I will pour out my spirit” (Joel 2:28-29 ESV). The personal and direct ministry of the Spirit would be extended to include all persons of every sort: every social-economic class, every age, both genders. This extension had already been proclaimed to Abraham at the very first. Connected with the establishment of God’s covenant with those who would become Israel was a look to their future:

Now the LORD said to Abram, “Go from your country and your kindred and your father’s house to the land that I will show you. I will make of you a great nation, and I will bless you, and make your name great, so that you will be a blessing. I will bless those who bless you, and the one who curses you I will curse; and in [or through] you all the families of the earth shall be blessed.” (Gen. 12:1-3 ESV)

The covenant promise made particularly to Israel would be extended to all peoples of the earth. This promise was regarded as being fulfilled at Pentecost as proclaimed by Peter and recorded in Acts 2:17. It is also celebrated in the book of Revelation with all the nations, people, languages of humankind represented there before the throne of God and the Lamb (Rev. 7:9).

Israel learned through their prophets that the covenant they lived by would be fulfilled sometime in the future both intensively and extensively by God himself. Such expansions, moving from promise to fulfillment, are a kind of continuity with discontinuity (relative difference). The fulfillment would far exceed what seemed to be originally promised. The fulfillment would bring about more than what was first anticipated, but not less. God would be more faithful to his Word than anticipated, not less.

Fulfillment, enduring purpose and the faithfulness of God

Throughout the New Testament we find that God was understood to be faithful to his Word, that the one who promises would be true to his Word and fulfill or keep the promise he had made. That faithfulness was ultimately demonstrated in the coming of Jesus. It came about through his incarnation and his whole life and ministry, including his death, resurrection and ascension. The word “fulfillment” is most often used to point out when the word of God as foretold in the Old Testament had come about. God’s word, Scripture, was being fulfilled in many of the details of Jesus’ life including his virgin birth, escape to Egypt, ministry in the Spirit, entry into Jerusalem on a colt, being rejected, the betrayal of Judas, his arrest, being abandoned by his disciples and his crucifixion.

The idea of fulfillment is also used several times in terms of God’s particular promises or in regard to the entirety of God’s purposes worked out in history in Jesus. Consider James 1:18 (NRSV): “In fulfillment of his own purpose he gave us birth by the word of truth, so that we would become a kind of first fruits of his creatures,” and Mark 1:15 (NRSV): “The time is fulfilled, and the kingdom of God has come near; repent, and believe in the good news.” Hebrews 6:17 (ESV) speaks of the “unchangeable character of his purpose” and in Ephesians 3:11 (ESV) we read of God’s plan for the church to proclaim the “eternal purpose which he has realized [or accomplished] in Jesus Christ.”

The idea of a promise being “fulfilled” is also found throughout the book of Acts:

And we bring you the good news that what God promised to our ancestors he has fulfilled for us, their children, by raising Jesus; as also it is written in the second psalm, “You are my Son; today I have begotten you.” As to his raising him from the dead, no more to return to corruption, he has spoken in this way, “I will give you the holy promises made to David.” (Acts 13:32-34 NRSV)

Note also Acts 7:17 (NRSV): “But as the time drew near for the fulfillment of the promise that God had made to Abraham, our people in Egypt increased and multiplied…”

Jesus himself spoke of fulfillment: “Do not think that I have come to abolish the law or the prophets; I have come not to abolish but to fulfill” (Matt. 5:17 NRSV). “The time is fulfilled, and the kingdom of God has come near; repent, and believe in the good news” (Mark 1:15 NRSV). “These are my words that I spoke to you while I was still with you — that everything written about me in the law of Moses, the prophets, and the psalms must be fulfilled” (Luke 24:44 NRSV). Jesus also could use the idea of such fulfillment involving the establishment of a “new” covenant: “He did the same with the cup after supper, saying, ‘This cup that is poured out for you is the new covenant in my blood'” (Luke 22:20 NRSV).

This fulfillment of all that was promised to Israel is explicitly proclaimed in over 55 passages in the New Testament, with the most comprehensive declaration being from Paul’s second letter to the Corinthians, “For in him every one of God’s promises is a ‘Yes.’ For this reason it is through him that we say the ‘Amen,’ to the glory of God” (2 Cor. 1:20 NRSV). Jesus Christ himself is the fulfillment of the covenant promise and enduring purpose of God!

We also are informed that the God revealed in Jesus Christ has eternal purposes (Eph. 3:11; Heb. 6:17) that are expressed in “the covenants of promise” (Eph. 2:12)—the promises being “irrevocable” (Rom. 11:29) and “unchanging” (Heb. 6:17). The God of Israel has purposes that are accomplished over time, and thus are not realized all at once. But God is declared to be faithful and does not give up on those purposes. His intentions to bring about an eternal purpose worked out in time, in our history, is reflected in God’s making and keeping his promises (Rom. 4:20). The book of Hebrews closes with a benediction that celebrates the Lord Jesus, the great Shepherd of the sheep, being brought back from the dead through the “blood of the eternal covenant” (Heb. 13:20).

While the term “fulfillment” is only used a few times in the New Testament, the idea of a promise coming to pass is pervasive and corresponds with God’s making promises to Israel who lives in covenant relationship with God. In English the most concise and direct way to indicate that what was promised has come to pass is probably to say that the promise was “fulfilled.” An alternative way is to say God “kept” his promise. The fulfillment of God’s Word must be connected to what was promised. An absolute separation, or disconnection, would mean that the promises were not fulfilled, or that what God did subsequent to making them was independent of his promises. It would mean that God did something other than what he had promised! The making of a promise by someone who is faithful requires grasping the continuity between the promise and its fulfillment. Promise plus faithfulness necessarily implies fulfillment.

The idea that God who is faithful has eternal purposes and made irrevocable covenant promises means that what God intends from the beginning is carried out, is fulfilled, at some time in the future. Also, the idea of purpose requires grasping some continuity between what comes first and what comes later if God is faithful. What is purposed has to be connected to its achievement, or fulfillment. Without that connection, our trust in God’s faithfulness to his Word would largely be content-less. Faithfulness means some kind of continuity that we can count on—a continuity that arises out of God’s nature and character. Otherwise God would be arbitrary and capricious, merely willful—and well, untrustworthy. Purpose plus faithfulness necessarily implies fulfillment.

How exactly God fulfills his promise or his eternal purpose, can radically exceed how those who originally heard the promise and even believed in his eternal purpose, had imagined! After all, God can do far more than we can ask or imagine (Eph. 3:20). That means there can and will be discontinuities—unanticipated and surprising discontinuities achieved with the fulfillment of the promise, especially if God is generous and superabundant. This is exactly what we see the New Testament church wrestling with. All of what was fulfilled in Jesus far exceeded what they had anticipated, thus creating discontinuities with former ways that they then struggled to understand (things like Jews and Gentiles eating together).

(public domain via Wikimedia Commons)

A new heaven and new earth

As noted already, the Old Testament prophets indicated the surprising scope of God’s covenant purposes in terms of its intensification and expansion. But with the coming of Jesus, we find that the fulfillment includes even more than what was explicitly indicated in the Old Testament. We see that it includes not only the rule and reign of God over all nations, rulers and powers (thus achieving God’s shalom—his peace, fruitfulness, no wars, etc.), but also the eradication of all evil and suffering. It includes the completion of the priestly ministry of Melchizedek anchoring our eternal union and communion with God through the Son of God and in the Spirit of God. This fulfillment reaches finally to the establishment of a new heaven and new earth! All this is often summed up by saying that Christ fulfills over all the cosmos the three offices granted to Israel: Prophet, Priest and King. This fulfillment of God’s covenant promise is not so much a discontinuity from the first covenant as it is the unfathomable glorification of it!

One covenant purpose in two forms?

One way that both the continuity and the radical discontinuity of the covenants has been expressed theologically is by saying that there is one covenant that God works out in two forms—promise and fulfillment. The old covenant has the form of promise and the new has the form of fulfillment. Taken alone, this summary statement cannot explain all we have addressed so far in this essay, especially how the old form of the covenant has been fulfilled in Jesus Christ and by the Holy Spirit and what the implications are. These theological terms, just like any, do not comprehensively explain themselves. You have to know what they summarize or synthesize before you can appreciate what it means and not misunderstand. But despite these limitations, many leading teachers down through the history of the church have found this phrasing both useful and faithful. It points us to the reality of who God is, to what he has done in relationship to his people and to his eternal purposes.

We find this phrasing used by Thomas F. Torrance and James B. Torrance in summing up the faithfulness of God throughout history, culminating in Jesus Christ. Note these quotes:

Ultimately therefore the Old Testament hope for redemption reposes upon the covenant will of God, extended to cover all nations, and it is this exalted understanding of the covenant will of God that leads them to see a new form of the covenant in which God will forgive iniquity and remember sin no more, as Jeremiah put it. (T.F. Torrance, Atonement, p. 41)

When we turn form the Old to the New Testament, we turn from the old form of God’s covenant to its new form, where it is perfectly and finally fulfilled. (T.F. Torrance, Incarnation, p. 56)

For Calvin, all God’s dealings with men are those of grace, both in Creation and in Redemption. They flow from the loving heart of the Father. The two poles of his thought are grace and glory—from grace to glory. There has been only one eternal covenant of grace promised in the Old Testament and fulfilled in Christ. “Old” and “New” do not mean two covenants but two forms of the one eternal covenant. (J.B. Torrance, “Covenant or Contract?,” Scottish Journal of Theology, p. 62)

This way of synthesizing biblical revelation by saying there was one covenant in two forms was made use of during the Protestant Reformation by Calvin, Zwingli and Bullinger. But over many years, the idea of two characteristically divergent covenants, with little to no continuity, developed as contractual ideas were imported into the biblical notions of God’s covenant (berith in Hebrew, diatheke in Greek). Eventually, there emerged the idea of two opposed covenants, one of nature or works and another of grace. This way of expressing it was first introduced, it seems, by Ursinus (about 1584) and received great impetus by being included in the Westminster Confession of Faith (1647) and a pamphlet bound with it, The Sum of Saving Knowledge.

The idea of multiple, characteristically divergent covenants became common throughout Puritan Theology, and what we now call the Federal Theology of many (but not all) Calvinists. The idea of multiple covenants, with each one spelling out entirely different ways God related to different groups of people at different times, reached an apex with the Dispensational Theology set forth in the Scofield Reference Bible of 1909. This publication, named after the American theologian C.I. Scofield, included his annotations to the biblical text that expounded this theology. It held that there were seven characteristically distinct covenants or dispensations of God dealing with various groups of humanity throughout history.

The benefits of the “one covenant in two forms” expression

Although speaking of one covenant in two forms (promise and fulfillment), is not the only way to formulate both the continuity and yet difference in God’s interactions with his people, it is a useful way to indicate in what way God’s original promise is worked out in Jesus Christ. (In similar fashion we could also speak of one purpose with different manifestations, or of one purpose with different stages of development, or of one covenant purpose in two forms of covenant—promise and fulfillment.)

This way of speaking about the covenant helps highlight the faithfulness of God by indicating significant points of continuity. It also conveys the character of the one Triune God as being coherent, trustworthy and consistent and so not arbitrary or capricious. It highlights God eternal purposes, bringing out the fact that all his interactions with humanity arise out of his Trinitarian love. It emphasizes that God is interested in having one kind of relationship with his people and through them with all people—a relationship of love and unconditional or freely-given grace. It helps us recognize the unity of the one people of God (in two forms) who are his representatives to all the world. It shows that the way God relates to his creation reflects outwardly through the progressive realization of his eternal covenant purposes—what is inwardly and eternally true of the glory of the triune relationships of holy love between the Father, Son and Holy Spirit. One God—three Persons. It conveys who our Triune God is.

Saying there is one covenant in two forms (or one covenant purpose in two forms of covenant) also has the advantage of corresponding most closely with the understanding of the covenant as a promise (vow or oath). It also corresponds closely with the biblical emphasis on fulfillment of the covenant of promise brought about in Jesus Christ.

However, we also should note that the “one covenant” terminology can lead to a certain amount of confusion. In some instances, Scripture speaks of more than one covenant, for instance in Galatians where Paul talks about two covenants or any time there is a contrast being made in how the people of God or Jesus himself is related to the Mosaic law under the new or second covenant, which fulfills the first. The theologians who originated the idea of “one covenant” were aware that the bible sometimes speaks in the plural (particularly in the contrasts being made in the book of Hebrews). But they were wanting to emphasize the continuity and thus the oneness of God’s character and eternal purpose. So they preserved the distinction by speaking of two forms of the one covenant. Since the word covenant exhibits both a unity and a diversity, it can be used in slightly different ways depending upon whether the unity of purpose or the difference between promise and fulfillment are being emphasized. They attempted to hold together both with this way of phrasing it since it would be a mistake to disregard one aspect or the other.

The problem of speaking about the covenant(s) is greatly exaggerated by theologies that de-emphasize or entirely neglect the distinction between the Abrahamic covenant and the Mosaic law. When the covenant and law are conflated and so confused, it is usually because the Mosaic law has been made so prominent that it swallows up the more foundational Abrahamic Covenant of promise. The whole of what is still called the old covenant is thus treated as a legal, contractual relationship—a system of merit. The result of this conflation has moved, ironically, in two opposite directions, with some moving toward legalism, and others toward antinomianism. Both are significant errors.

Those who move in the legalistic direction (as in Sabbatarianism), so conflate covenant and law (with the Mosaic law given prominence), that there is little to no recognition of the difference between living under promise and living under Christ’s fulfillment. Consequently, one’s relationship with God becomes essentially understood in a contractual or legal way. If grace comes into the picture at all, God’s giving it is made, in whole or in part, conditional upon what we do. In some Roman Catholic circles and many Protestant-style cults, this is popularly understood as God mercifully giving us some kind of merit system that, because of Christ’s merits, he graciously counts as adequate, but knows in reality it is not. In Protestant liberalism we simply have to follow Jesus’ example and build the kingdom here on earth for him instead of exclusively following an Old Testament prophet and building up the exclusive kingdom of Israel. From this point of view, the Christian life is focused on defining just exactly what particular demands and expectations God has and trying very hard and doing our very best to conform to them. What the current applicable “laws” or requirements are, can have an almost unimaginable range depending upon what group takes this approach.

Those who move in the antinomian direction (meaning no need or place for obedience) also conflate the first or old covenant with law, reducing it all to a system of legal merit. But then a dichotomy (complete separation) is imagined between that “old covenant” (which is really Mosaic law) and an entirely new and discontinuous “new” covenant that is all about grace. With these two opposing alternatives, the clear choice is grace not law (old covenant). The grace of God in this case essentially means not only the abolishment of the old covenant/law but also the elimination of any need for a relationship of trusting obedience to God. From this perspective, grace means that God simply overlooks and makes exceptions to all wrongs. Thus grace has no obligations at all and God’s love is reduced to his being nice and accepting of whatever we manage to give him. From this perspective, grace is like a blanket covering over everything and everyone automatically, mechanically, impersonally, universally and indiscriminately. Grace calls for no particular response nor does it have a particular shape of relationship with God. Grace is simply a fact of the universe, an impersonal flow, part of nature. The old covenant with its law got everything completely wrong. God’s love as shown in Jesus means he accepts and approves of everything and everyone just as they are. He is happy to leave us wherever he finds us.

Bringing out the unity of God’s covenant purposes worked out in promise and fulfillment and the place of the obedience of faith in God’s grace called for under both forms or phases or dispensations (grace promised and then fulfilled) works against both of these errors. It is for these reasons and others that this essay seeks to clarify our use of some of these biblical and theological terms.

Speaking of one covenant (and so emphasizing continuity over discontinuity) gives voice to God’s eternal faithfulness in his relationships with his people on the basis of a unilateral and unconditioned grace that calls for the response of faith, hope and love. Though the understanding of one covenant brings out continuity, all difference is not ruled out—the distinction between promise and fulfillment is upheld by the qualification of there being two forms of covenant—promise and fulfillment. Were there no differences (distinctions) there would not be these two forms. This idea of oneness (continuity) with distinction (difference) reflects well the nature of God who is one in being and three in Person (unity with distinction).

These are the primary reasons for expressing our understanding that there is a very significant continuity between what are often called the old covenant and the new covenant. These fundamental reasons prevent us from regarding the two covenants as being absolutely separated in a way that would not allow for any sort of continuity between them. However, to avoid confusion but still indicate both continuity and the distinction between promise and fulfillment, we can speak of one covenant purpose in two forms of covenant—promise and fulfillment.

Abrahamic covenant in relationship to the Mosaic law

The idea that the two covenants are sharply separate and thus discontinuous, derives, in part, from the few verses of Scripture that by implication contrast the old and new covenants. However, the idea of radical discontinuity comes mostly from passages that contrast not the two covenants but two distinct implementations of the law—under the covenant in the form of promise, and under the covenant in the form of fulfillment. Given what we have discussed so far, were the two covenants actually radically discontinuous as some believe these passages teach, we’d end up with two incompatible assertions: 1) that the covenants are connected and involve some kind of continuity, and 2) that the covenants are absolutely discontinuous and thus separate, even at odds. Because both assertions cannot be true, we need to consider the passages that point to discontinuity, asking whether the distinctions noted unambiguously require us to take the differences between the covenants absolutely (or the difference in implementation of the one covenant as absolutely discontinuous). We also need to consider how the law fits into our understanding of God’s eternal purpose and covenant.

The passages of Scripture that do seem to set up an old/new contrast are far fewer in number than English translations of the Bible would lead us to believe and they do so only by our inferring old from new (seven passages) or by our inferring new from old (one passage only). There is no instance of this exact contrast of old vs. new covenant. While it is not wrong to make such inferences, they can be misleading and must be corrected or qualified by the actual contrasts that are being made—most prominently between the first and second or between the first and new covenants.

A careful study reveals that the greatest contrasts made are not between the covenants, but between the law and life in the Spirit, or between the law and the new covenant—a distinction that makes a significant difference. The greatest difference is thus not between the two covenants, but between our understanding of the law and its place in the lives of those living in covenant relationship with God before and after that eternal purpose and promise is fulfilled in Christ.

These strong contrasts involving the law do not require an absolute difference between the covenants. Only a very few instances of such contrasts made between the law and the new covenant (not between the two covenants) even leave open the possibility of radical discontinuity. It turns out that conclusions of radical discontinuity depend upon improper understandings of the wordings offered in some English translations regarding the law. Unfortunately, it is upon these few verses that theologies of absolute distinction have been built.

It is important to keep in mind that a critical distinction between the Abrahamic covenant and the Mosaic law is assumed by the biblical authors—a distinction that we must account for in our understanding. Also, when considering all that is said in the New Testament about law, we find four separate issues, each addressed by Paul, which must be distinguished:

- The problem of discontinuity of practice according to the Mosaic law.

- The issue of the inherent limits of the Mosaic law as originally given.

- The serious problem of the misuse of the Mosaic law.

- The affirmation that there remains a certain continuity of the good purpose of the Mosaic law and the continuing element of obedience out of faith in God’s grace upon fulfillment of the covenants (Abrahamic and Mosaic law) made with Israel.

It is critical that we understand which of these four issues is being addressed when various contrasts are being made in Scripture. Note that all four involve explaining changes in our relationship to the Mosaic law, including changes in the practice of ministry. These changes involving law are not the same as changes to the covenant from promise to fulfillment. The contrasts being made in these passages are about changes in the practices of the people of God brought about by the fulfillment of the covenant in Christ.

Levitical law and the new covenant in Hebrews

In looking at these four issues involving the law, we need to consider a number of passages that make a clear contrast between the purpose and place of the law before and after Christ’s fulfillment. We’ll discover that even these passages indicate a certain continuity as well. We’ll start with the book of Hebrews and then move on to Paul’s understanding.

An understanding of changes in application of the law on the basis of the fulfillment of the promise or covenant is pervasive throughout the book of Hebrews. The author is concerned primarily with Jesus Christ and his priesthood and its relationship to the Aaronic priesthood (as set out in the Levitical law of Moses) and the difference made by Christ’s fulfillment of the promises of the covenant. As the author of Hebrews notes, “Christ has obtained a ministry that is as much more excellent [than the old Levitical ministry of priests] as the covenant he mediates is better, since it is enacted on better promises” (Heb. 8:6 ESV). The question being addressed in this verse involves the legitimacy of Christ’s enactment of priestly ministry in contrast to the requirements of the Levitical laws regulating Israel’s priesthood. Christ’s priesthood is under question since it does not conform to the stipulations of Levitical law. But the author’s answer about Christ’s non-conformity to the Mosaic law involves bringing up God’s covenant and promises. The covenant and promise are presented as the proper, deeper and more enduring basis upon which to judge the form that Jesus’ priestly ministry takes. The argument is that there is a radical discontinuity in how the priestly ministry is carried out. However, it is a legitimate discontinuity because Christ’s ministry is based on a “better” covenant and on “better” promises that Jesus, the eternal Son of God, mediates. On that basis, not on the basis of the Levitical law, the result is that Christ’s ministry is a “more excellent” mediatorial (leiturgias, priestly) ministry.

The author of Hebrews does also make a contrast between the two covenants. The word for better (kreitton) is a comparative word that indicates what is more useful or serviceable or advantageous. It is better because it is stronger, more fully developed. By its greater strength it is able to completely fulfill a task, compared to that which is weaker. This comparative word is used in 12 passages in Hebrews to illustrate that what God has done through Jesus Christ the eternal Son surpasses what was available beforehand.

The comparison of better indicates not a complete disjunction, or opposition, but a significant improvement. The better promises and covenant built upon the former and resulted in Christ’s ministry being far more excellent than what a merely human Levitical priest could ever hope to accomplish. The first covenant was not able to fulfill itself nor were human beings. Only Jesus Christ, the Son of God, could bring about its full purpose, its fulfillment. But to do so he did not conform to the Levitical norms of the Mosaic law. It was the Son’s non-conforming ministry that brought about God’s greater purposes intended from the beginning. Better thus indicates a relative, not an absolute difference.

A wrong or faulty first covenant?

In looking at this topic, some are thrown off by some less-than-helpful translations of a word in Hebrews 8:7, which describes not the law but the covenants. There the need for a “second” (covenant) is explained in terms of a particular description of a “first covenant.” The word used most often to characterize what the first covenant lacked is its failure to be “faultless” (amemptos) or “blameless.” Some translations say that it was “wrong.” These translations can make it seem that the first covenant was morally evil, in serious error, spiritually defective, distorted or broken and so contrary to God’s purposes, at least after Christ has completed his earthly ministry. In that case, it would be hard to see how it could have any place in God’s will and purpose at all, ever, if God has a consistent character and purpose, the one revealed in Christ, and was faithful from beginning to end. The word itself is referring to something that is not deserving of condemnation. However, what connotation we take away must account for the immediate context of what was just previously said about the second covenant being comparatively “better.” We must recall the larger context of everything else said about the idea of covenant and promise, and about God who is faithful to his Word of promise in the whole of the New Testament.

We should regard what is lacking not as a moral or spiritual fault. How could a promise or covenant set up by God be so? Rather, what is lacking is a practical matter, namely that it was unable to achieve what it pointed to. It did not have the strength, maturity or power to bring about its own fulfillment. The word “faultless” then connotes weakness, inability, not moral or spiritual wrong or defect. And this is what the new covenant enacted by the Son of God could indeed achieve and what made the second better and thus necessary to bring about God’s eternal purposes. That is what differentiates the “first” from the “second” covenant. The difference is again a relative one, not an absolute one.

As indicated earlier, the descriptors of first and second do not convey the idea of complete separation, but of an order, a sequence, or even of a development. First and second do not require thinking of a radical discontinuity between what is first and second.

However, an admitted radical change in ministry practice according to law is said to be legitimate on the basis of Christ’s acting on what is comparatively “better” and which leads to what is “most excellent.” There is, then, a certain kind of change related to the covenants—from weaker to what is stronger and more fully developed and in that sense better. But is that change best conceived of as discontinuity?—as disjunction or absolute separation of covenants? It seems not. The greater and admitted change by far is between the particular former ministry practices of the human priests according to Levitical law compared to the Son of God’s ministry practices. The later ministry brings about a far greater fulfillment than those who practiced the Levitical law ever could. Why the radical change in the ministry practice of priesthood according to Levitical law?—because of the relative change in the covenant from what is weak and unable, to what is strong and thus able to accomplish God’s more excellent purposes by his Son. The first covenant could not be fulfilled in and through the Levitical law included in it, so radical change was necessary.

The fulfillment of the covenant changes our relationship to the law

Beginning in Hebrews 8:8 (ESV), the author cites Jeremiah 31:31-34, which speaks of a “new covenant” that will not be like the covenant made with their fathers who did not continue in God’s covenant. This new covenant involves God’s putting his laws into their minds and writing or inscribing them on their hearts so that he will be their God and they will be his people (Heb. 8:10). The result of this covenant will be that his people will “know the Lord” directly and thus personally (Heb. 8:11) and “I will be merciful towards their iniquities and I will remember their sins no more” (Heb. 8:12 NRSV). The difference here is that what has been given in the past is now put in their minds and their hearts. What is different is the relationship of the people to the law (nomos) not so much a change in the law itself. So a certain continuity is affirmed even with the law, while there is still a great, almost unimaginable, superiority to what God did with the law and what the results are for his people by the ministry of the Holy Spirit.

(public domain via Wikimedia Commons)

First covenant obsolete?

In Hebrews 8:13 (ESV), the author sums up the contrast this way: “In speaking of a new covenant he treats the first as obsolete. And what is becoming obsolete and growing old is ready to vanish away.” The word obsolete can be misunderstood, especially when the context of this book and the whole of the New Testament is not taken into consideration. In context, the range of meaning of obsolete is significantly narrowed. What is obsolete is not opposed to the new but is old in the sense of growing old or worn out, and so is in the process of vanishing. The idea here is of something that was begun having reached the end (telos) of its usefulness. Therefore, what is needed is another work of God to pick up and take much farther what he had begun. The two covenants are related by the one continuing purpose of God that connects them. But the fulfillment leaves behind what is no longer needed once the second work of God has been enacted. The baton, as it were, has been passed. The second work of God is not, then, a completely new thing that is disconnected or unrelated to what God had begun. But what was begun required a second act of God to complete it and so bring about a radically new situation that the first covenant started but could not complete. The old can be said then to be no longer useful once the second covenant has carried forward what had been begun. The task of the first had been completed and so declared “obsolete.” No longer is it the defining document of God’s relationship with his people—the “better” covenant is.

Other contrasts in the book of Hebrews regarding the form of Christ’s ministry and the non-conformity to priestly ministry under the Levitical law are between “copy” and “shadow” (Heb. 8:5 ESV) and between the “true form” of the reality vs. the “shadow” (Heb. 10:1 ESV). Again, these images do not set forth absolute contrasts but rather continuity with radical distinction between the more real or substantive compared to what came first.

While a contrast is brought out between the two covenants, the continuity of God’s intentions, worked out in these covenants, is plainly expressed in Hebrews:

When God desired to show more convincingly to the heirs of the promise the unchangeable character of his purpose, he guaranteed it with an oath, so that by two unchangeable things, in which it is impossible for God to lie, we who have fled for refuge might have strong encouragement to hold fast to the hope set before us. (Hebrews 6:17-18 ESV)

Here the continuity between the two covenants is related to expressions or manifestations of God’s faithfulness and single purpose. This being so, however we understand the discontinuities/differences in the covenants as noted in the book of Hebrews, we cannot call into question the “unchangeable character of [God’s] purpose.”

The law in relationship to the covenant promised and the covenant fulfilled

In the book of Romans we find both continuity of purpose and radical discontinuity between the situation before and after Christ. The contrast Paul makes is primarily between being justified or made/declared righteous by “works of the law” over and against “by grace through faith.” Alternatively expressed, the contrast is between life “under the law,” “in the flesh” or under the “power of sin” in contrast with living “in Christ” or “in the Spirit” (Rom. 7:5-6, 11, 13, 17, 20, 23; 8:2-17). The issue is thus not a contrast between two covenants, but a contrast between two different relationships to the law—one before Christ and the other after Christ’s earthly ministry was completed and the Spirit had been sent and received by those who are now members of the Body of Christ. These contrasting dynamics in relation to the law (or forms of obedience) are worked out under the overarching trajectory of God’s promises (Rom. 4:13-14, 16, 20; 9:9; 15:8) or covenant purpose (Rom. 9:4; 11:27).

The theme of promise and fulfillment is brought out in the first sentence of the book of Romans. There Paul identifies himself as one “set apart for the gospel of God which he promised beforehand through his prophets in the Holy Scriptures, the gospel concerning his Son, who was descended from David…” (Rom. 1:1-3 ESV) The rest of the book is a demonstration of God’s faithfulness to fulfill through Jesus what was promised. There is a presumed continuity throughout between what God did in the past with what he has done in Christ, from promise to fulfillment. But within that overarching single and “irrevocable” gift (Rom. 11:29 ESV) and purpose, there is also a discontinuity of how we are now able to live in relationship to God (see also Eph. 3:11 ESV: “according to the eternal purpose that he has realized in Christ Jesus our Lord”).

Consistent with what Paul says elsewhere about the distinction between the covenant established with Abraham and the law established with Moses, in Romans that “connection with distinction” is maintained. By the law (nomos), Paul seems to be meaning the particular commandments given to Moses for God’s people, which include the Ten Commandments and also the other commandments given to Israel contained in the books of Exodus, Leviticus and Numbers, then further explained in Deuteronomy. These commandments given to God’s covenant people include directives concerning the consequences of disobedience and the proper ways to worship God and seek God’s forgiveness. How that is to be lived out under the conditions of the covenant now fulfilled by and in Christ is the question and controversy that Paul is addressing.

Note that Paul never equates the Abrahamic covenant or promises with the Mosaic law, even though they became inseparable in the life of the Israelites. For Israel, the law is contained within their covenant relationship given to them with God through their father Abraham. The key is to recognize both the distinction and connection in the life of Israel between covenant or promise and the law.

Misuse of the law under the covenant promise

In his responses to objections raised against his teaching, Paul brings up the factor that the law has been abused and misused by God’s own people. Thus he not only explains the proper place of the law in the life of Israel, but also how it has been distorted. The key phrase that indicates the misuse is “the works of the law.” This amounts to a distrusting, disbelieving and contractual approach to their relationship with God, which ignores God’s covenant purposes and promises and attempts to merit God’s blessings and favor largely by one’s behavioral (external, we might say) conformity to particular laws or commandments stipulated in the Mosaic law.

But this approach, according to Paul, is a gross distortion of the purpose for the commands/laws—a distortion projected onto the character of God and the kind of relationship he intends to have with his people. The result is that the promise is considered to be in opposition to the law and that the law has somehow annulled the promise, superseding it. That is why Paul has to denounce in particular these two false beliefs. The law and a contractual works-righteousness approach to keeping it had come to define in a distorted way their relationship with God.

Paul says that this understanding is wrong. The promise is the permanent basis of relationship with God and it calls for a response of trust or belief in God and his word. The law should have never been approached in a “works of the law” contractual way (Gal. 3:21-22). The law was added to the promise (Gal. 3:19), to serve as a custodian or tutor until “faith” or “the faithful one” was revealed and “until Christ came.” After Christ, the faithful one, came, we are no longer under that old tutor (the law), but live in Christ as children of God through faith in him, in his faithfulness (Gal. 3: 23-26). The law was to be lived out on the basis of counting on the covenant as promise. The law did not establish a second basis in itself that annulled the first basis (Gal. 3:17). Paul emphatically rejects that idea. A works-of-the-law approach was always a misuse of the law, which displaced the covenant relationship of trust in God’s faithfulness.

In Galatians 3:10-14, Paul uses the word “law” as shorthand for “works of the law.” In Gal. 3:13, he says we have been redeemed from the curse of “the law” while in Gal 3:10, he says those who rely on the “works of the law” are under a curse. We thus understand verse 13 to be saying either that we have been redeemed from the curse of “works of the law,” or that we have been redeemed from the consequences of failing to live out the law by faith, in contrast to Abraham, who did live by faith. The point is that we are not redeemed from the law itself, but from the curse that results from depending upon the law. Therefore, when Galatians 3:12 (NRSV) says “the law does not rest on faith” we take that to mean that the “works of the law” do not rest on faith. Paul goes on to explicitly declare that the law was never based on works—it was always based on faith (Rom. 9:32).

Faith or trust and obedience to God’s commands in the Old Testament

Israel was commanded to believe or have faith in God’s faithfulness. For example, Psalm 62:8 (ESV) exhorts: “Trust in him at all times, O people; pour out your heart before him; God is a refuge for us.” Faithlessness is denounced in Israel—note Jeremiah 5:11 (ESV): “For the house of Israel and the house of Judah have been utterly faithless to me, says the LORD.” In Deuteronomy 1:26 (ESV), Moses explains to the people that they had “rebelled against the command of the Lord” and “did not believe the Lord your God.” Moses and Aaron were not allowed to enter the land of promise “because you did not believe in me” (Numbers 20:12 ESV). The author of Hebrews links disobedience to unbelief or being faithless: “To whom did he swear that they would not enter his rest, if not to those who were disobedient? So we see that they were unable to enter because of unbelief.” (Heb. 3:18 ESV). Distrust or unbelief in God is an act of disobedience and in that sense a violation of an essential part of God’s law that referred them back to God’s covenant heart and promises. The commands of God were never set up to bring about “works of the law”—obedience to God apart from faith in God. The Ten Commandments begin with a rehearsal of what God has done for Israel as the reason for them to obey: “I am the Lord your God who took you out of Egypt” so on that basis trust me and obey these following commands. The only obedience God wants is the obedience that comes from faith in him—faith in his faithfulness.

Limitations of the law

We need to be aware of the intrinsic limitations of the law:

- It cannot fulfill the promise God made and was never intended to do so (Romans 8:3).

- It has been misused and distorted by the power of sin making use of the weakness of human nature (flesh).

The law is powerless to prevent its own misuse. It is also unable to transform and perfect human nature and so bring humanity into right relationship with God. Given these serious limitations, the law must be superseded by God’s intervention to deal with them both if the promise or covenant and God’s ultimate purposes are to be fulfilled. This is exactly what God has done in Jesus Christ and by the Holy Spirit.

The “problem” is not with the covenant or promise, but with the limitations and weakness or deficits of the law. The law was never the basis of Israel’s unilateral covenant relationship with God, which was to be lived out by faith in God’s faithfulness—not faith in the law but faith in the promises, in God’s covenant love and purposes. The law could never prevent its misuse nor fulfill God’s purposes as laid out in his covenant.

Christ as the end (telos) of the law

Perhaps the verse used most often to argue for an absolute difference between the covenants is Romans 10:4 (ESV): “For Christ is the end (telos) of the law, that everyone who has faith may be justified.” Note that Paul is speaking of the law, not the covenant or promise. Transferring what is said here about the law to the covenant is a misapplication. Next note that it is easy to think that by “end” of the law, Paul means an absolute end to all that preceded it—the covenant and all of the Old Testament commands. But this understanding requires two things: that we select one of two different meanings in English for “end,” and that we conflate law with covenant and so make them identical.

We have already dealt with the mistake of collapsing covenant and law together. But what about the law? The word translated, “end” is telos. This type of “end” means the fulfillment of a purpose or the reaching of the final (end) stage of a process, or the goal of growth or development, as in maturing. It can also mean bringing to perfection or completion. Telos then corresponds with the idea of fulfillment. Paul is saying here what Jesus said of himself, namely that he came to fulfill the law not abolish it. Nevertheless, there is a certain discontinuity at work here. Christ did what the law itself could not do. He completed what it began. It is in that sense that Christ brought the law to its goal, aim or end (telos). And since he has, it is no longer needed in the way it formerly was. Its purpose was achieved. Its task completed. God in Christ accomplished much more than this, but we don’t have time to address it all.

The obedience that comes from faith

Fulfillment does not mean there are no commands to obey or obligations in the life of the believer in Christ and his grace. Paul could not be more emphatic in stating that we are not to sin (Rom. 6:1-2). No matter what the change in our relationship to the Mosaic law, it does not amount to the elimination of all commands, of all obligations, of all obedience. Everything has been put on a new basis, lived out under the covenant now fulfilled—no longer simply promised. But the covenant has not been eliminated.

There is also a continuity between the lives of people before and after Christ. Both were to obey by their faith in the grace of God. That is what righteousness amounts to. That is why Abraham is called the father of faith (Rom. 4:6) and we are presented in Hebrews 11 with the long list of those Old Testament examples who “obeyed by faith.” Paul describes the aim of his whole ministry as working to bring about “the obedience that comes from faith”—a phrase that bookends his letter to the churches in Rome (see Rom. 1:5 and Rom. 16:26).

Law lived out always on the basis of faith, whether promised or fulfilled

Early on in ancient Israel there were some, like many of the religious leaders in Paul’s day, who attempted to fulfill the law and so attain righteousness (right relationship with God) through their own law keeping. Speaking of such people, Paul pronounces that they could not succeed in doing so because they “did not pursue it through faith, but as if it were based on works” (Rom. 9:32 ESV). Being “ignorant of the righteousness that comes from God” and so in error, they sought “to establish their own” righteousness and did not “submit to God’s righteousness” (Rom. 10:3 NRSV). Paul then explains in Rom. 10:4 (ESV) that this righteousness from God comes from Jesus who is the “end” (telos) of the law—he is the one who fulfills all righteousness for us. The only righteousness Paul wants to share in or to receive is Christ’s righteousness, not any righteousness he could achieve on his own, even if perfect! (Phil. 3:7-9). The only righteousness God intends for us is to share in Christ’s righteousness. That is how the just requirement of the law (right relationship) will be fulfilled in us by the Spirit (Rom. 8:4).

From the beginning, God was interested only in a response and relationship of faith in his faithfulness, goodness and grace. He never intended a works-righteousness relationship with his people. God never set up a contractual, mutually obligating or conditioning relationship. Such was not worthy of the God of Israel. Israel was to live by faith in the God who promises. Now as Christians, we are to live by faith in the God who fulfilled his promise in Christ. We obey by faith in who God is and what he has given to us.

Continuity of the purpose and character of the law

Despite the discontinuities in how we relate to God’s commands, first under promise and then under fulfillment, Paul argues for a continuity of God’s purpose and character involving his giving of the law. He declares that the law is “holy, and the commandment is holy and just and good” (Rom. 7:12). In response to the charge that the law is sin he retorts, “Certainly not!” (Rom. 7:7). He calls the law both good and spiritual (Rom. 7:13-14) and says he delights in God’s law (Rom. 7:22).

The power of sin takes advantage of weakness of the law