Dear Brothers and Sisters,

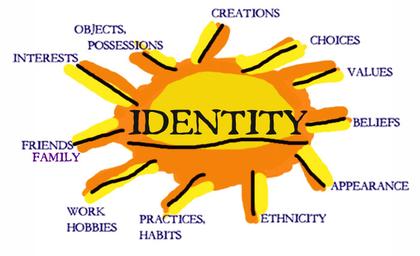

When asked to define their identity, people reply in various ways. Many focus on what they do—I’m a plumber… an engineer… a homemaker. Others refer to traumas of the past—I’m a recovering alcoholic… I’m a former prisoner. Some take on identities assigned to them by others—She’s wealthy… he’s homeless… she’s a snob. Though some of these are superficial, they all, for better or worse, can powerfully shape the way a person self-identifies.

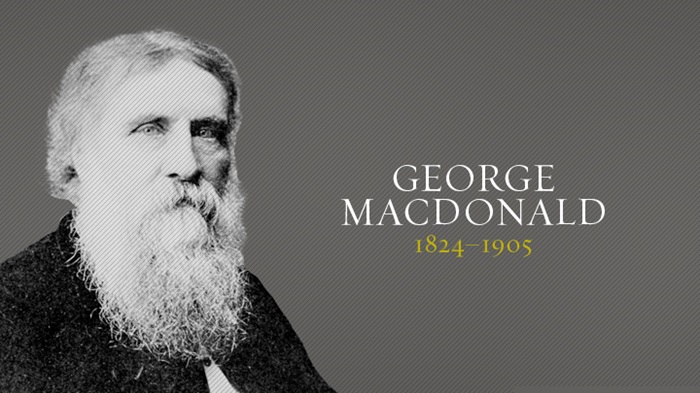

Speaking of personal identity, I recently ran across this insightful statement from Scottish pastor, theologian and author George MacDonald:

I would rather be what God chose to make me than the most glorious creature that I could think of. For to have been thought about—born in God’s thought—and then made by God, is the dearest, grandest, and most precious thing in all thinking.

George MacDonald is credited with being the father of fantasy literature. A mentor to author Lewis Carroll, he also strongly influenced C.S. Lewis, J.R.R. Tolkien and G.K. Chesterton. His literary works, including his sermons, are excellent (several are on my “to read” list).

It begins with knowing we are loved unconditionally

Though MacDonald understood that God created us to be glorious creatures who are made in his image, many Christians don’t grasp that truth. Though they know Christ died for them while they were yet sinners (Rom. 5:8), they don’t yet understand that God loves them because of who they are in relationship with him, rather than because of what they have done (or not done). That is a good thing because when it comes to what we have done or left undone, we all have fallen short of God’s glory (Rom. 3:23). Thankfully, God loves us unconditionally with the same love by which he loves Jesus. Note these words in Jesus’ high priestly prayer for us:

I have given them the glory that you gave me, that they may be one as we are one—I in them and you in me—so that they may be brought to complete unity. Then the world will know that you sent me and have loved them even as you have loved me. (John 17:22-23)

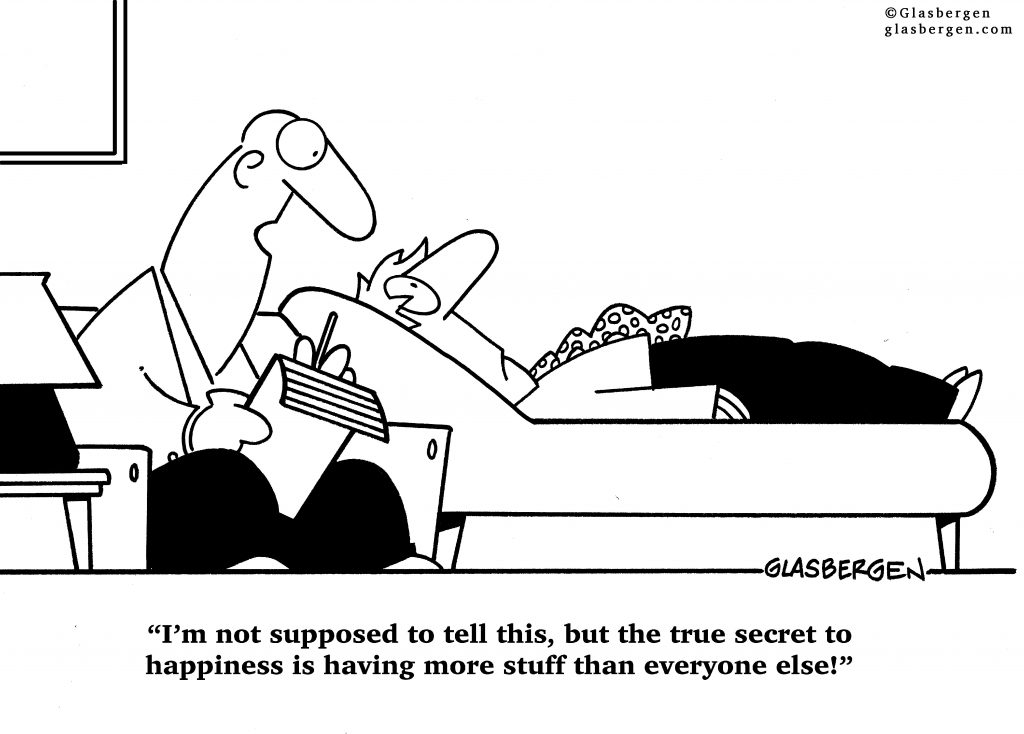

We then reject false identities

In reflecting on the profound nature of God’s love for us, I found myself humming the song, Looking for Love in All the Wrong Places—the tragic behavior that is the lot of far too many people in our world (Christians included). It’s a fundamental, vital truth that we cannot find true fulfillment in ourselves because we were created to reflect God’s glory. Seeking to gain glory for ourselves from ourselves will never lead to lasting fulfillment. Glory can only be received as a gift from another who has it to give. Where we look to find our identity says a lot about what we think will give us that glory.

I have enjoyed many jobs in my life, starting as a paperboy delivering the daily newspaper via my trusty old bicycle. I then worked as a box boy at the first Trader Joe’s Market, a custodial floor crew cleaner, a child-care worker, an administrative assistant, a customer service training supervisor, a church pastor and a church administration director. As much as I have enjoyed these jobs (and a few others I did not list) my true identity is not derived from any of them. My true identity is in Christ—no more, no less. I praise God that my identity is not in the things I’ve done, nor is it in the things that have been done to me. God gives me my identity in him and that is a gift of free grace. I am his, body and soul.

Tragically, some people find their identity in victimhood. Most of us have been victims, some much more tragically than others. I would never want to minimize or trivialize anyone’s pain and suffering resulting from being victimized, but equally tragic is becoming so defined by a past event that it is as if a stake was driven deep into the ground connected to a chain, that then is fastened around their neck so they can never move beyond the perimeter of that past event.

We embrace our true identity

Though we will experience suffering in this life—sometimes at another person’s hand—the gracious Lordship of Jesus means we can live with confident hope knowing that no past event can determine the future God has for us, no matter how horrific that event was. The power of God’s redemption through the crucifixion of Christ demonstrates in no uncertain terms that God can overcome all evil and bring out of all suffering things of eternal value. Our true identity thus comes from the future that God, in Christ, holds out to us. Nothing can rob us of that goodness and glory!

An understanding of and confidence in our true identity in Christ changes how we live here and now, looking forward with hope to our eternal future. This perspective even helps us gain a new perspective on our past suffering. That doesn’t mean we minimize it, nor does it mean we look on it with joy. However we are no longer victimized by it—it no longer defines our identity. We know that God redeems all things in Christ, and that includes the evil from which we have suffered and even the evil we have committed that led to the suffering of others. Indeed, we have hope in the redeeming power of God to put all things right.

We know nothing can take it away

While a prolonged illness or a seemingly irreconcilable difference with loved ones may oppress us and deprive us of many good things, they cannot change who we are in Christ. Nothing can take away our inheritance as his beloved children. The actions or words of others may rob us of something we have worked for such as a higher grade or a job promotion, but again, no one can take away what God has in store for us for eternity. When our identity is in Christ, we know that we can and will identify with Jesus in every facet of his earthly life, and that includes his sufferings.

The important dynamic here is that just as Jesus’ sufferings were not wasted nor a hopeless event, neither are ours. God can use our joys and our sufferings as a part of our sanctification. Just as we suffer with him for a while, so we will be glorified with him. Our hope is just as the apostle Paul taught in the book of Romans:

The Spirit himself bears witness with our spirit that we are children of God, and if children, then heirs—heirs of God and fellow heirs with Christ, provided we suffer with him in order that we may also be glorified with him. (Rom. 8:16-17 ESV)

We cannot experience the good that comes from suffering if we stand apart from Christ, refusing to entrust to him all our sufferings. But when we entrust all we are and have to Christ, God uses our suffering to help us gain an eternal hope, with Jesus Christ, the Crucified, as the Redeemer of all things. C.S. Lewis put it this way: “Pain insists upon being attended to. God whispers to us in our pleasures, speaks in our consciences, but shouts in our pains. It is his megaphone to rouse a deaf world.”

And so we live into our true identity

Realizing that our true identity is in Christ, we seek to have God’s glory shine through all aspects of our life. We no longer seek to conform to the culture of this world, which, among other things, fallaciously tells us that we can separate our sex from gender, or even choose whatever race or ethnicity we’d personally prefer, regardless of our genetics. The apostle John gave this instruction:

Do not love the world or the things in the world. If anyone loves the world, the love of the Father is not in him. For all that is in the world – the desires of the flesh and the desires of the eyes and pride in possessions is not from the Father but it is from the world. And the world is passing away along with its desires, but whoever does the will of God abides forever. (1 John 2:15-17 ESV)

The stark reality is that if we are not seeking to find our identity solely in Christ, then we are seeking it in something else. As the Holy Spirit helps us grow in understanding that our true identity is in Christ, we are freed to enjoy and glorify him in the unique ways he created us to be. In Christ we are righteous, made holy and totally loved. In him we are enabled to bring glory to God, not by our own doing, but through his gifts and blessings.

Though our identity tends to be shaped by many factors (see the diagram above), our conversion deepens as we abandon any images of ourselves that are not from God. Instead, we embrace what God says about us, knowing that he is pleased with how he defined and created us, body and soul. The heart of receiving our sanctification is to live in trusting fellowship with Christ, holding to what the apostle Paul explained in saying that God has “set his seal of ownership on us, and put his Spirit in our hearts as a deposit, guaranteeing what is to come” (2 Cor. 1:22). I praise God that he makes clear to us that our identity is not determined by what we do, what we possess, or by the opinions others hold of us. Instead, our identity is defined by God, by who we are in gracious relationship to him.

Celebrating our true identity in Christ,

Joseph Tkach

PS: Please join me in praying for all those devastated by Hurricane Maria and the earthquakes in Mexico. We are grateful that, according to initial reports from the Caribbean Region and Mexico, our members were spared loss of life and serious injury. Details about property damage are sketchy—we’ll let you know more as details come in. In the meantime, you can click here to watch a video showing damage to the island of Dominica. Our members Cris and Mary Vidal live there, right next to Castle Comfort shown in the video. Thankfully, though their roof was damaged, it did not blow away. If you’d like to help GCI members who will need financial assistance due to disasters like the recent ones, congregations can donate to the GCI Disaster Relief Fund (for information, click here).