Dear Brothers and Sisters,

It’s an important spiritual discipline, yet many people (Christians included) misunderstand and even fear meditation. Perhaps this is because they have in mind its non-biblical forms, which generally involve disengaging the mind from temporal existence through various practices including repetition of particular words or phrases. In contrast, biblical meditation is about actively engaging one’s mind with a focus on divine revelation.

Scripture teaches the practice of meditation. Note this verse: Tremble, and do not sin; meditate in your heart upon your bed, and be still (Psalms 4:4 NASB). In place of meditate, other translations have search (NIV), ponder (ESV) and commune (KJV). Perhaps these words remind us of times we’ve been deep in thought lying in bed before rising in the morning, or before falling asleep at night. Biblical meditation gives focus to such thoughts by framing them within our life in Christ, considering how we can participate or have participated with our Lord in his life and love.

Transformed thinking

Rather than emptying the mind of thought, biblical meditation involves filling it with the knowledge of God—of who he is, and of our life in him and his presence in us. This focused way of thinking is also about absorbing the life and love of God as we ponder actions we might take in given situations. As we do, the Holy Spirit transforms our thinking, helping us develop more godly responses. As we practice the spiritual discipline of meditation, this pattern of thinking becomes second nature—almost automatic. The more we meditate, the more we’ll find ourselves making right decisions.

Though no analogy is perfect, we can liken biblical meditation to the response of a baseball player at bat. Though the best batters are born with excellent hand-eye coordination and vision, much practice is needed to become highly skilled. A pitch traveling 90 mph takes approximately .4 seconds to reach the batter, giving the batter only about .2 seconds to make a decision before swinging (or letting the ball pass). The batter then has only about .2 seconds to swing. If he or she misreads the speed of the pitch by as little as 1.5 mph, their swing will miss by a foot. Because a bat is at most 2.75 inches thick at its fattest part, missing by only an inch will cause the batter to miss the ball entirely, or at best hit a soft grounder or a weak fly-ball. But with much practice, the batter’s swing becomes more accurate—the timing and adjustment of his or her swing becomes second nature.

Though no analogy is perfect, we can liken biblical meditation to the response of a baseball player at bat. Though the best batters are born with excellent hand-eye coordination and vision, much practice is needed to become highly skilled. A pitch traveling 90 mph takes approximately .4 seconds to reach the batter, giving the batter only about .2 seconds to make a decision before swinging (or letting the ball pass). The batter then has only about .2 seconds to swing. If he or she misreads the speed of the pitch by as little as 1.5 mph, their swing will miss by a foot. Because a bat is at most 2.75 inches thick at its fattest part, missing by only an inch will cause the batter to miss the ball entirely, or at best hit a soft grounder or a weak fly-ball. But with much practice, the batter’s swing becomes more accurate—the timing and adjustment of his or her swing becomes second nature.

Biblical meditation is like that—it’s a form of practice (spiritual discipline) in which the Holy Spirit cultivates within us a God-attuned “timing.” Eventually our “trained” (second-nature, automatic) response will be to more fully experience fellowship with God in our lives.

Two ways of knowing

In “Meditation in a Toolshed,” C. S. Lewis wrote about the different ways we look at things: “You can step outside one experience only by stepping inside another. Therefore, if all inside experiences are misleading, we are always misled.” Though Lewis did not believe that we are always misled in life, he did think that certain ways of knowing are more fundamental and direct than others. He recommended we draw a distinction between looking at the effects created by something or someone (the analytic way of knowing) and looking along something to its source (the participative way of knowing).

In “Meditation in a Toolshed,” C. S. Lewis wrote about the different ways we look at things: “You can step outside one experience only by stepping inside another. Therefore, if all inside experiences are misleading, we are always misled.” Though Lewis did not believe that we are always misled in life, he did think that certain ways of knowing are more fundamental and direct than others. He recommended we draw a distinction between looking at the effects created by something or someone (the analytic way of knowing) and looking along something to its source (the participative way of knowing).

The analytic way involves understanding something about the quantitative effects of something on other things apart from ourselves—like studying the wake of a ship that has already passed us. We mostly get to know something about things that way. We can call this the more objective approach, although all knowing involves to one degree or another both objective and subjective elements.

The participative way of knowing involves understanding the object itself and its qualitative effects upon us. In this approach we look directly at the source or object of our knowledge and pay attention to the whole range of effects it has upon us and the responses it draws out of us. This more subjective approach pays much more attention to the affective, internal and personal interaction with the object of knowing. This is knowing something itself, not merely knowing about something.

Lewis used the experience of being in love to make his point. The analytic, more objective way of knowing involves viewing something being experienced by someone else who is said to be in love, analyzing what is seen without reference to any love the observer might have experienced themselves. In this mode, the observer might refer to biological stimuli or to various behavioral reactions.

By way of contrast, the participative way of knowing about love considers the subject’s more direct experience of participating in the relationship and the qualitative effects upon the person. This view takes account of every aspect of the relationship experienced as a whole. Consideration of one’s own experience of love is used to come alongside the person and to interpret their experience of love, accounting for that person’s emotions, thoughts, actions, moral and religious/spiritual considerations, and other responses generated by the love and the short- and long-term effects of the relationship.

Experiencing God and his blessings

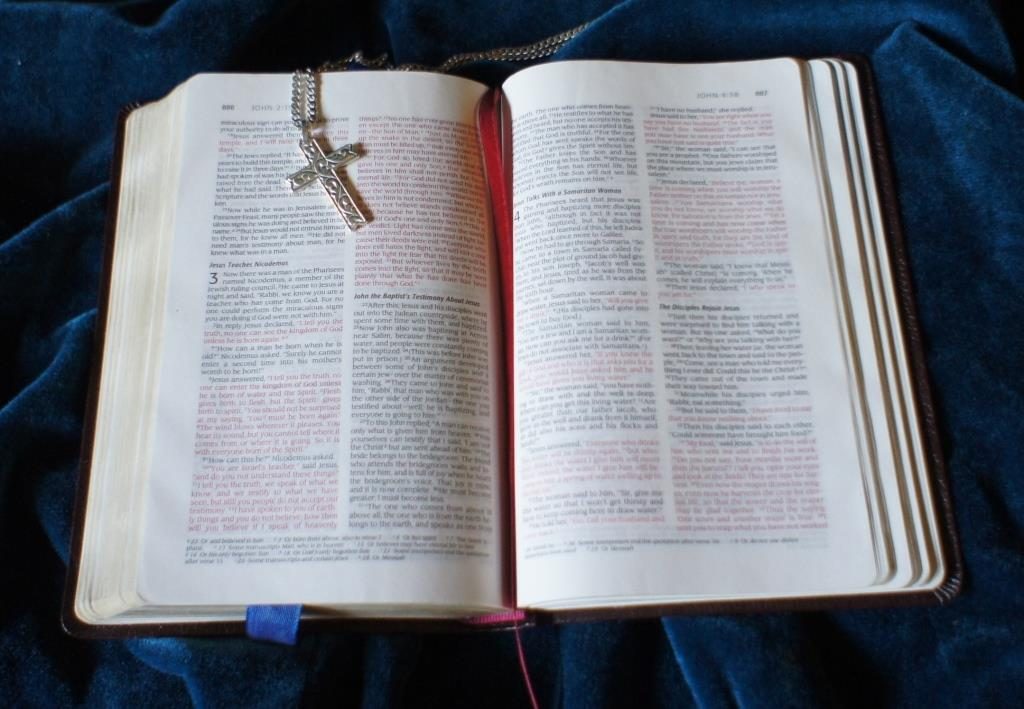

Now let’s think about these two ways of knowing in terms of Christian meditation. This form of meditation involves looking at a verse or passage of Scripture from both perspectives. Practicing an analytic way of knowing, we consider the words, grammar and historical-cultural context of the passage to see what it most likely meant to the original audience and the effects upon those who originally received the message. Then we practice a participative way of knowing, considering what the biblical revelation means for us today.

By his Holy Spirit and through his preachers and teachers in the church, God speaks to us both individually and collectively through Holy Scripture. Our God has not stopped communicating, and the primary object of the knowledge he communicates to us through his revelation is who he is and who we are in relationship to him.

Such knowledge draws out from us the response of worship, expressed through repentance, faith, hope and love. Through Scripture, we come to know not just the words of the Bible, but become personally addressed and engaged in knowing the source and subject of the Bible: God himself! As we look at the Bible and find we can look along it to its Author who speaks again today, we find that we can know and trust him with all we are and all we have.

The Bible is a readily available gift of revelation from God that is designed to help us both objectively and subjectively. We can look at it subjectively because it is the only book in the universe that has the author present with us as we read it. Equally important to reading the Bible and enjoying its narratives is reflecting (meditating) on God’s revelation to us, realizing it is also revelation for us. T. F. Torrance reminds us that thinking about Scripture should be ordered from a Trinitarian theology of revelation: God the Father speaks through the incarnate Son of God and we are given ears to hear and know this Triune God by the ministry of his Holy Spirit in us.

Meditation, like the other spiritual disciplines, is not a self-help tool designed to help us get closer to God so that he will love us more. Rather, it enables us to experience a relational dependence on God’s grace, which he has already fully given to us in Christ. As C. S. Lewis said, “In silence and in meditation on the eternal truths, I hear the voice of God which excites our hearts to greater love.” Though he was not talking about hearing an audible voice, he did have in mind being sensitive to the lead of the Holy Spirit as he shapes our understanding of God and of our responsiveness to God’s Word.

The source of all our knowledge about God is his revelation of himself in Christ through the Holy Spirit. Grasping this Trinitarian relation is our hermeneutical base for how we read the Bible, enabling us to meditate on how we should act in any given situation. As we, through meditation, ponder our response to certain situations (past or future), the Spirit is working to transform us in our approach to God and in how, through thought and action, we participate in the divine nature of our triune God.

When we interpret the Bible relationally, we are able to experience and apprehend God in the reality of his own words and acts. As T. F. Torrance taught, “indwelling God’s Word” is an acquired habit of looking through Scripture and allowing God’s message to be “interiorized” in our minds. As we allow God to retain his own majesty in our knowing him, he will preside in all our judgments of him and of others.

As we conclude using my baseball analogy, we should note that as we surrender to the lead of the Holy Spirit in our lives through meditation, we will experience more “extra base hits” and “home runs” in our lives. And that will be a very great blessing!

Enjoying the extra bases of God’s love and life,

Joseph Tkach

_____________

Notes:

- The bottom three pictures in this letter are public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

- To read an article from the C. S. Lewis Institute on the topic of Biblical meditation, click here.