Dear Brothers and Sisters,

As foundational doctrines of the Christian faith, justification and sanctification are loaded with meaning and historical significance. However, they often are misconstrued, resulting in misunderstanding the related doctrines of salvation by grace and the Christian life. Though we can’t explore these doctrines in depth in a single letter, I want to point out here an error often made in explaining justification and sanctification.

As foundational doctrines of the Christian faith, justification and sanctification are loaded with meaning and historical significance. However, they often are misconstrued, resulting in misunderstanding the related doctrines of salvation by grace and the Christian life. Though we can’t explore these doctrines in depth in a single letter, I want to point out here an error often made in explaining justification and sanctification.

All aspects of salvation are in Christ

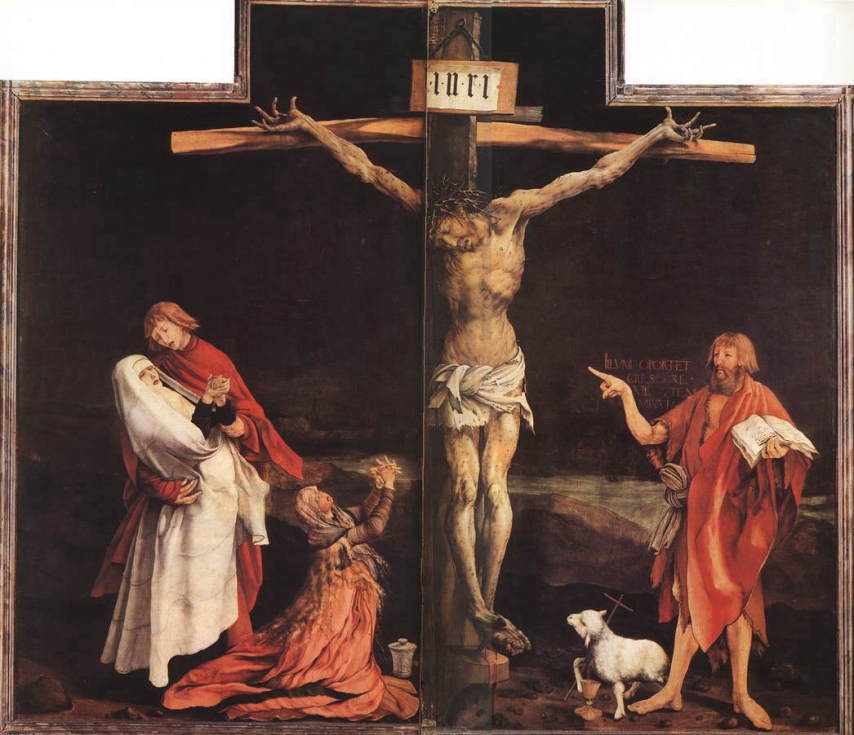

Let’s begin by noting that the doctrines of justification and sanctification belong together and, like all aspects of salvation, are related entirely to the work Jesus Christ does as our representative and substitute. According to theologian Karl Barth, justification and sanctification weave together three vital topics: 1) divinity (that Jesus is fully God), 2) humanity (that Jesus is fully human), and 3) the uniting of divinity and humanity (two natures) in the one person of Jesus Christ. The core Christian doctrines of the Trinity and the Incarnation tell us that justification and sanctification, as two related aspects of the one event of salvation, take place entirely in Jesus Christ who, in his vicarious (representative and substitutionary) humanity, acts on our behalf and in our place. Therefore when we think about these doctrines, as illustrated in the painting below, we must look to Jesus and nowhere else (and that includes our own works).

Note John the Baptist at right—as the last of the old covenant prophets,

he points to Jesus as the one source of salvation.

(public domain via Wikimedia Commons)

Justification in Christ

It is common to believe that though God justifies us in Christ, justification only becomes actual for individuals when they profess personal faith in Christ. Only then, it is believed, will God forgive and reconcile them to himself. The mistake in this line of reasoning is believing that our personal decision for Christ triggers a change in God’s mind toward us, thus changing the way God relates to us. But that thinking turns our relationship with God into a sort of contract wherein God sets out certain conditions for him to extend to us the benefits of Christ’s justifying work.

According to this faulty reasoning, our personal response to God (our faith) conditions God’s response to us. The net result is to view God as having two minds concerning his human creatures. Which mind he has depends upon our human response to a potential—with God being for some (and their salvation), and against others (wanting their damnation). Who Jesus Christ is and what he has done, then, only represents God’s mind, heart and purposes toward a few, namely those who respond appropriately to God with faith. Though perhaps unintentional, this reasoning misconstrues faith as a human work, with one’s response of faith becoming the central concern.

The nature and place of faith in our justification

To see faith as a human work misconstrues both faith and Jesus Christ. Faith is our response to the truth and reality of who God is and what he has done for us in Jesus. Because of who Jesus is (the God-man) and what he has done and is doing, God is for us, God is merciful, God is forgiving, God is saving. In Jesus, God has removed every obstacle to his being reconciled to us. In our place and on our behalf, Jesus has done for us what we could never do for ourselves. Faith, then, is our response to this truth—our response to a reality that has been accomplished for us already by and in Christ. Faith is the way we receive all the benefits that Christ has secured for us already.

Placing our faith (trust) in God is good and proper. We are obligated to trust in God since he is trustworthy and has clearly demonstrated that trustworthiness in Jesus Christ. To refuse to trust God for his grace is sin. But some will ask: “What if I don’t have sufficient faith?” The answer is that God, by the gracious work of the Holy Spirit, gives us the gift of sharing in Jesus’ own faith in his Father. When it comes to salvation, we do not count on the strength and purity of our own faith. Instead, we trust Jesus, who as our great high priest, offers his perfect faith to the Father on our behalf. By the Spirit Jesus draws us up to share more and more in his perfect response to the Father.

It is vital to understand that our response of faith toward God is not on our own. In responding to God, we share in the gift of Jesus’ own response. The Torrance brothers referred to this as the dual mediation of Christ. Jesus not only mediates God’s blessings to us, but he, in our place and on our behalf, mediates our responses to God. Note this from T.F. Torrance:

Through union with [Christ] we share in his faith, in his obedience, in his trust and appropriation of the Father’s blessing; we share in his justification before God. Therefore when we are justified by faith, this does not mean that it is our faith that justifies us, far from it—it is the faith of Christ alone that justifies us, but we in faith flee from our own acts even of repentance, confession, trust and response, and take refuge in the obedience and faithfulness of Christ—“Lord I believe, help thou mine unbelief.” That is what it means to be justified by faith. [1]

The gospel truth is that Jesus Christ himself is our justification. Our justification is the “once and for all” reality that has been fulfilled both objectively and subjectively [2] by Jesus, on our behalf, in his own human (subjective) response to the Father, by the Spirit (1 Corinthians 1:30 ESV). Justification is thus not about what we do—it’s about what Jesus has done, is doing, and will continue to do as our substitute and representative. Therefore we rightfully say that we are justified by the grace of God in Jesus Christ—a grace we receive by the gift of faith.

Sanctification in Christ

In speaking of our sharing in Jesus’ own faith for our justification, we have already begun to speak of our sanctification. Sanctification is the process of growing up in Christ—of sharing more and more in Jesus’ perfect responses to the Father in the Spirit. By God’s justifying work, we are put in right relationship with God, and by God’s sanctifying work we begin to respond as we share by the Spirit in Christ’s responses for us. As we do so, we share more and more in Jesus’ sanctification of the human nature that he continues to share with all human beings.

You will recall that Jesus, who never sinned, was baptized, thus confessing sin on our behalf. As human, he also grew in wisdom and stature and learned obedience. In his humanity he overcame temptation. In the power of the Spirit he sanctified himself and prayed for our sanctification. Jesus then gave himself up on the cross as his final act of faithful obedience to his Father, by the Spirit. Jesus did all these things for us—for our sanctification. As Paul declares, Jesus not only is our justification (righteousness), he also is our sanctification (1 Corinthians 1:30 ESV).

Sanctification is no less a gift of God’s grace than is justification. Like justification, sanctification is God’s work that we, by the Spirit, receive as we trust God to do that sanctifying work in us. What Christ has done for us in his incarnate life, the Spirit works out in us. As Karl Barth wrote, God “sanctifies the unholy by his action with and towards them, i.e., gives them a derivative and limited, but supremely real, share in his own holiness.” [3]

To be sanctified is to be set apart as holy, and it should be obvious that we cannot do that of ourselves. It is God who sanctifies us. Paul noted that Jesus took upon himself our unholiness (sin), “so that in him we might become the righteousness of God” (2 Corinthians 5:21 ESV). It is Jesus’ own holiness that he imparts to us by his action as one of us and on our behalf. As the author of Hebrews notes, “We have been sanctified through the offering of the body of Jesus Christ once for all” (Hebrews 10:10 NASB). For emphasis, the author then repeats his point: “For by one offering he has perfected for all time those who are sanctified” (Hebrews 10:14 NASB).

Our sanctification (holiness) is Jesus’ own sanctification. As C.S. Lewis wrote, “Holiness is not a result of self-willed moral effort but is a divine activity.” It is God’s presence and activity to express his holy character in man by his grace through Jesus Christ. We are always dependent upon God. As Paul explained to the church in Thessalonica, our sanctification is God’s will (1 Thessalonians 4:3 ESV). When we realize that our holiness is not our own, but is from, through, and by Jesus, our conduct will be exemplified by humility (not a holier-than-thou attitude) as we follow the lead of the Spirit in sharing in Jesus’ own holiness.

From start to finish, it’s about Jesus

From start to finish, both justification and sanctification depend entirely upon Jesus—on who he is (the God-man), and on what he has done and continues to do, by the Spirit, in his human nature as our representative and substitute. Therefore we trust Jesus—we participate in his faith (faithfulness) as the “author and finisher” of our faith, including our justification and sanctification.

Delighted to be justified and sanctified in Jesus,

Joseph Tkach

_________________

[1] “Justification: Its Radical Nature and Place in Reformed Doctrine and Life.” Scottish Journal of Theology, volume 13, no 3. pp. 225-246.

[2] Note here a subtle, yet important point: We must avoid the mistake of dividing justification into objective and subjective parts, with the objective being what Jesus does, and the subjective being what we do. That mistake implies that we, somehow separate from Jesus, respond to God on our own. Were that true, we’d be thrown back on ourselves apart from Jesus. Thankfully, the truth is that we personally (subjectively) participate in Jesus’ own (subjective) response made in his humanity on our behalf. Jesus does not just do the objective work in our justification and sanctification—his work is both objective and subjective, and in both cases that work is done in our place and on our behalf. So, how then do we talk about a “personal response” to Jesus without creating the problem mentioned above? The Torrance brothers did so by referring to Jesus’ subjective (personal) responses and of our sharing, through the Spirit, in Jesus’ own subjective responses.

[3] Church Dogmatics, volume IV, page 500.

In an article on the GCI website, GCI president Joseph Tkach addresses our shared mission and vision as churches journeying together by the Spirit in Grace Communion International. The article begins with this statement:

In an article on the GCI website, GCI president Joseph Tkach addresses our shared mission and vision as churches journeying together by the Spirit in Grace Communion International. The article begins with this statement: