Here is part 8 of an essay from Gary Deddo on the nature of the church and its ministry. For other parts of the essay, click a number: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12. We encourage you to add your thoughts and questions in the “comments” box at the end of each post to get a discussion going. To read the full essay in booklet form, click here. To read the related essay, “Clarifying Our Theological Vision,” click here.

A Brief Theology of the Church

(with a view to equipping the saints for the work of ministry)

by Dr. Gary Deddo

Part 8: Relationships within the body of Christ

Last time we looked at Paul’s comparison of the church (the body of Christ) to the human body. Paul compares Christ (the head of the church) with the head of a human body, which governs, oversees and so regulates the different “members” of the body. Though this comparison did not control Paul’s understanding of the relationship of Christ with his body, the church, there are overlapping points that we need to understand.

In comparing the human body to the church, Paul took advantage of the intuitive sense in ancient times that life flows from and so is directed by a person’s head, out into and through the body like a river that begins at its source or head-waters, then flows downstream into a river. Seeing, hearing and speaking—all the fundamental communicative aspects—came from the head, not the other parts of the body. Thus severing a hand or leg, for example, would have a very different effect than decapitation, which would always lead to death of the whole body. So the head was thought to have life-giving, life-directing authority over the whole body.

In various passages in his epistles, Paul makes use of this asymmetry of relationship between the head and the body to point to both vital connection and asymmetrical dependence. Paul’s point is that Christ has absolute authority as Lord to give and direct the life of the members of his body who belong to him in closest association. Unlike the relationship between the human head and human body, Christ is in no way dependent upon his body, the church, and the church is utterly dependent on its head, Jesus Christ.

Paul also used the head/body comparison to indicate that Christ himself, by the Spirit, coordinates the action among the many, diverse members of the body. Without Christ as its head, the various limbs and parts are unable to act in harmony. Thus Paul regarded Christ, the head, as ordering or harmonizing all the functions of his body, the church, giving it coordinated unity even though it has many different, distinct members. In that regard, note these two passages:

To each is given the manifestation of the Spirit for the common good…. God has so adjusted the body, giving the greater honor to the inferior part, that there may be no discord in the body, but that the members may have the same care for one another. (1 Cor. 12:7; 24-25 RSV)

Speaking the truth in love, we are to grow up in every way into him who is the head, into Christ, from whom the whole body, joined and knit together by every joint with which it is supplied, when each part is working properly, makes bodily growth and upbuilds itself in love. (Eph. 4:15-16)

These passages make clear that the members of the body are to relate not only to their head, Jesus Christ, but also to each other. Paul is making this point because (particularly in Corinth) he is addressing churches on the verge of dysfunction, if not outright disunity. The kind of unity with difference or diversity that God seeks to bring about in his people, the church, is beyond what nature, especially fallen and corrupted human nature, is able to produce. Such unity is the fruit of belonging to Jesus Christ. On its own, fallen human nature tends towards either individual autonomy (yielding social anarchy), or towards externally enforced uniformity (yielding totalitarianism). Human societies tend to swing from one extreme to the other, and then back again. God’s way of unity with difference is a unique expression of his agapē love.

Ruled by love

Paul’s governing insight was that all relationships between persons or groups of persons are to be informed, moved and regulated and so disciplined by God’s agapē love, provided as a gift of grace to his people. This love purifies and cleanses and repurposes the natural loves: family love, marital love and friendships. That love is first demonstrated in the relationship between the Triune Persons, seen concretely in Jesus in his relationship with the Father. Secondly, it is seen in Jesus’ words and deeds towards all he came in contact with. That love culminated in Jesus giving his life for us in his crucifixion and resurrection, ascension and promised return. So every word and act of the members of his body in relationship to each other are to be moved and measured by conformity to and even sharing in God’s kind of love.

The crowning passage that lays this all out is 1 Corinthians 13, where Paul concludes corrective instruction to the church related to its lack of unity, causing them to be poor witnesses to Christ and keeping them from experiencing the fullness of Christ’s life-giving, fruitful love. In Corinthians 13 (often called the “love chapter”), the love of God, which was displayed in the life of Christ, is beautifully described in words. Paul wrote this passage to spell out clearly that it is only as we share in and live out of our relationship to Christ and his love that we are able to relate to one another in ways that bring about a fruitful unity and diversity in loving relationship, fellowship and communion.

Fruits govern gifts

Other related passages are Romans 12:6-8, where Paul lists some of the gifts of the Spirit, given for ministry. In Galatians 5:22-26, Paul addresses the fruit of the Spirit, which along with Colossians 3:12-15 addresses the attitudes and behaviors that ought to be exhibited by those who belong to Christ. These passages, like 1 Corinthians 13, describe the shape of God’s kind of agapē love that was visible in the life of Jesus. The upshot is that the many gifts given to us by the Holy Spirit are to be exercised according to the fruit of the Spirit—both are from the one Spirit ministering in each person’s life. The gifts and the fruit should not be disconnected in our practice of ministry. Gifts used in a way that do not exhibit the fruit of the Spirit are being misused. Such misuse needs to be discouraged.

A certain kind of unity with a certain kind of difference

Let’s look at a few things in Paul’s teaching found in these passages about relationships in the life of the church. First, Paul teaches that there are real differences between the various members. The particular differences mentioned have to do with the variety of gifts given to the church, each uniquely contributing to Christ’s continuing ministry. In particular, Paul notes that these differences are ordered (structured or arranged) so that they work together, or complement one another. But the different parts are not interchangeable; they are not equal in that sense. The hand is not the foot; the ear is not the eye. There are more presentable and less presentable parts.

This insight, that the differences mean that no member with their gift is interchangeable with another, and so are not equal in that sense, is bound to offend modern-day, Western thinkers. Inter-changeability is practically the one and only test of just and right relationships in our culture. Equality of any and every sort is measured by that criterion—are the persons interchangeable? If not, the situation is judged to be unequal and therefore unjust, not to mention unloving.

In that social/political framework, equality, equity and justice are thought to be achieved primarily by removing all significant differences between people so that they are interchangeable. That has become the predominant test of right relationship in the modern West—a norm that has extended into every area of modern democratic life so that it now extends far beyond the economic or political spheres of life to include the most personal of relationships, not just between government and citizens or between employer and employee. The near ubiquity of this simplistic and secular norm of justice has led to the church uncritically absorbing it into its own life—often promoted in terms of demanding individual “rights.” However, it is not to be that way within the church, the body of Christ.

The gift of salvation is not a right, nor is being a member of the body of Christ. How one then serves in the church is not a right (and that includes ordination). In short, the body of Christ is not a one-person, one-vote democracy (even if some of the ways it functions might make use of democratic mechanisms to accomplish some of its less personal tasks).

Furthermore, inter-changeability is not the test of love, equality, or even justice in the church. Our equality is in our relationship with Jesus Christ, and in our shared and equal need for his grace and love. We all are equal before the Lord at the foot of his cross. We all stand there equally under our Jesus’ direction and lordship. We all worship him alone and live in submission to him and to his good and right will according to his Word. We are equally recipients of his grace!

In our relationships with one another, we are not equal in every respect—we are not interchangeable parts. Each one of us has something to give the body that others can’t, and each must receive from others what they can’t give themselves. We are given these different, non-interchangeable gifts for ministry (service) in Jesus’ name. We all serve as our Lord’s representatives, sharing our gifts and receiving from others as God has arranged, ordered and structured the non-interchangeable members of the one body of Christ. In that way, all our relationships can bear fruit by the irreducible difference among the members coordinated by Christ, who is our unity.

Abuse of the differences

Because we live in the “present evil age,” the differences that exist between members can open up opportunities for abuse. This is true even though we are joined to Jesus Christ and participate by the Spirit in his sanctified human nature—the “stain of sin” continues to take its toll. Because that is so, Paul addresses this problem. Some of the Christians he was writing to were misusing the differences of ministry giftings to assert their superiority over others. Others were reacting to the differences by declaring their autonomy saying, “I have no need of others.” Some apparently denigrated themselves as having lesser gifts, ones less “respectable,” and saying they had nothing to offer.

Paul declares that all of these, perhaps natural, responses are distortions. All the gifts for ministry are given as God pleases. He distributes them as he sees fit. The wisdom behind the difference and distribution of gifts is that the body of Christ needs a whole range of gifts. But that does not mean that they cannot be harmonized or that all are not valuable. Paul declares that Christ can indeed enable them to work together to build up the body, with each member having an important part to play, contributing to the common good. It takes God’s agapē love to eliminate pride, envy and jealousy and the friction they generate so that there can be a fruitful gift exchange allowing the body to “upbuild itself in love,” as Paul indicates (see Eph. 4:12-13). This is the purpose for the beautiful unity and difference in the body of Christ.

Non-hierarchical order

Given the brokenness of our imaginations, we have a difficult time thinking that there can be order and structure if it is not one of hierarchical power. Sometimes the only alternative to hierarchical power we can imagine is one of individual autonomy and self-sufficiency. It seems that we can’t imagine a non-hierarchical order or structure to life. So we often tend to eliminate hierarchy and with it order or structure and put everything and everyone on a level plane, where the differences are ignored or eliminated and each individual does his or her “own thing.” When that approach doesn’t work, we then seek to reestablish relationships of hierarchical power and control that forces a certain kind of uniformity on all, accepting the fact that such imposition of external power will violate any substantial differences and thus hinder true free gift-exchanges between all members, great and small.

Though this dilemma is especially prevalent in the West, no society is able to manage easily or naturally the unity and difference exhibited in the body of Christ. It is common for the differences between persons or groups to be used by the stronger to take advantage of the weaker. But the solution is not to eliminate the differences, for when that happens, especially at the level of more personal kinds of relationships and especially in the church, persons are damaged in the opposite way. Each will seek to assert themselves, seeking self-sufficiency, becoming isolated, lonely and not likely particularly productive. Or alternatively, each will simply conform in a tightly uniform way to an external, impersonal power and control, muting any real freedom, creativity and unique contribution. The natural way of fallen human societies runs towards one extreme or the other—towards totalitarianism or towards anarchy.

Differences used to bless

In the body of Christ, through the work of the Spirit, under the lordship of Christ, the differences between members become a source of blessing to others, not an excuse to take advantage of others. The differences are of God’s gifting and those differences are life-giving. They make possible the wonderful gift exchange that can take place when pride is put in its place at the foot of the cross. Giving and receiving can be free. The exchange of gifts becomes part of our participation in the resurrection of Christ’s love among us. When all our “strings” are attached to Christ, we can love one another with no strings attached. When that happens, the new humanity founded in Christ begins to show through.

The kinds of differences that are good, right and fruitful in the body of Christ are not moral differences (right relationship between persons) nor are they at root spiritual differences (right relationship with God). All expressions of healthy difference remain under the Lordship of Christ and the exercise his kind of love—a love, designated agapē in the New Testament. This kind of love has a certain shape that brings glory to God and demonstrates his purposes for humanity.

Not every kind of diversity

Not all differences of every kind belong in the body of Christ. Unity in Christ does rule out certain kinds of differences, including those that are inherently divisive. The kinds of differences Paul speaks of in his epistles are ones of gifts of ministry for the common good given by the Holy Spirit. We can designate these as “practical differences.” These differences are not moral, having to do with right and loving relationships between persons involving right and wrong behavior/interaction, nor are they spiritual, having to do with right relationship (right faith, hope and love) between God and humans, in Christ, according to scriptural teaching. How we use the differing gifts, however, is a moral and spiritual issue! All gifts of the Spirit must be used according to the fruit of the Spirit.

This is why we have, along with the teaching about a proper unity and diversity of the body of Christ, directives on church discipline indicating that there are those who are to be corrected in love regarding wrong relationships between members. Such discipline, at times, can lead to individuals being excluded from regular participation in the fellowship (see 1 Cor. 5:1-5, 9-13; Gal. 6:1; 2 Thess. 3:15; 1 Tim. 1:18-20; 2 Tim. 3:1-5; 4:1-5; Titus 1:5-16; 3:8-11). When done in true love (agapē), such discipline, even if it means disfellowshipping, will be exercised with the hope of repentance, reformation and eventual reconciliation.

That not all differences can be tolerated within the church is also indicated by the many passages of Scripture warning against false teachers and admonishing adherence to the teaching of the apostles. That teaching, which was authorized by Christ, faithfully captures the truth and reality of God’s revelation culminating in Jesus Christ. Certain differences can arise that attack and undermine the unity found in Jesus Christ and sustained by the Holy Spirit. So God gives his body compassionate and wise members who are to exercise discernment, and on that basis practice church discipline. It is the responsibility of church leaders to “discern the spirits” (1 John 4:1) and the key to doing so is to know Christ and his Word and to be in consultation with others.

Jesus’ judgment not condemnation

Jesus made such discernments in his own ministry. Though he welcomed all, not all stayed with him. He offered stiff and direct words of warning to those who resisted him and his revelation of the Father—those who rejected their need for mercy and grace. While Jesus extended God’s forgiveness to all, he warned against those who rejected God’s grace, especially those who rejected the Holy Spirit of God who he would send in the Father’s name. Jesus recognized the spiritual danger of rejecting his freely-given grace and mercy, and especially of rejecting the Holy Spirit and his witness to Jesus Christ, the eternal Son of God. He would not have been loving with God’s kind of love had he overlooked this fact and instead just aimed to be nice or leave everyone alone.

Jesus’ words about not judging are completely misunderstood if taken to mean no one—not even pastors and overseers in the church—should exercise discernment and discipline in the body of Christ. Jesus’ words in the Sermon on the Mount about not judging do not amount to a simple, absolute command. What he says is this: “Judge not that you be not judged.” He then explains what he means: “For with the judgment you pronounce you will be judged and the measure you give will be the measure you get.” He goes on to direct his listeners to first judge themselves: “First take the log out of your own eye and then you will be able be able to see clearly to take the speck out of your brother’s eye.” Clearly, all judging is not ruled out—only a certain kind of judging. You must start with yourselves, and then only judge in such a way that first you judge yourselves and then judge others in the way you’d want others to judge you. In fact, Jesus’ words at that moment are words of judgment—he is discriminating between those who judge wrongly and those who judge rightly. Jesus words are always a judgment in the sense that they call for discernment and decision. His words sort things out—they shed light into darkness so we can see what is what. Right judgment always involves love and truth and starts with ourselves individually and as a church.

Though many note that Jesus did not condemn the woman caught in adultery, what is often missed is Jesus’ words of judgment spoken to the threatening elders: “Let him who has no sin cast the first stone.” Jesus was judging their intentions and so leading them toward repentance—in this case their withdrawal. We should also recall what Jesus said to the woman: “Go and sin no more.” Though Jesus judged that her actions were sinful, he gave this admonition with no hint of condemnation. Judgment is not always the same as condemnation. All condemnation is the end result of a process of judgment. But not all judgment leads to condemnation.

We must not assume that judgment means condemnation. In fact, if a right and true judgment-discernment-discrimination is made and received, condemnation is avoided (as in the case of the elders who decided not to stone the woman). Condemnation comes when a good and right judgment, such as God’s, is rejected rather than received. While we often judge in order to condemn, Jesus’ warnings and judgments are always given in order that those he loves might not experience condemnation.

Love, truth and church discipline

Love without consideration for discerning the truth and what is good, is not love. Pronouncing the truth with no concern for love, which desires the avoidance of final condemnation, is callous and unforgiving. In biblical teaching, love and truth work together (Eph. 4:15, 2; Phil. 1:9-11; 2Thess. 2:10). Love and discernment are both required. This process of discernment and exercising discipline is a derived responsibility of the church under the Word of God (Living and written) and by the Holy Spirit. In this way, the church maintains the kind of unity the Spirit has given to it—a unity that involves the exercise of a kind of diversity that does not undo the unity. It is a kind of unity that does not quench the Spirit’s diverse gifts for ministry (Eph. 4:3).

The church, then, is the place where God, by his Spirit, enables and frees his people to enjoy the unity and diversity of the body of Christ under the headship of Jesus its Lord and Savior in its worship and witness.

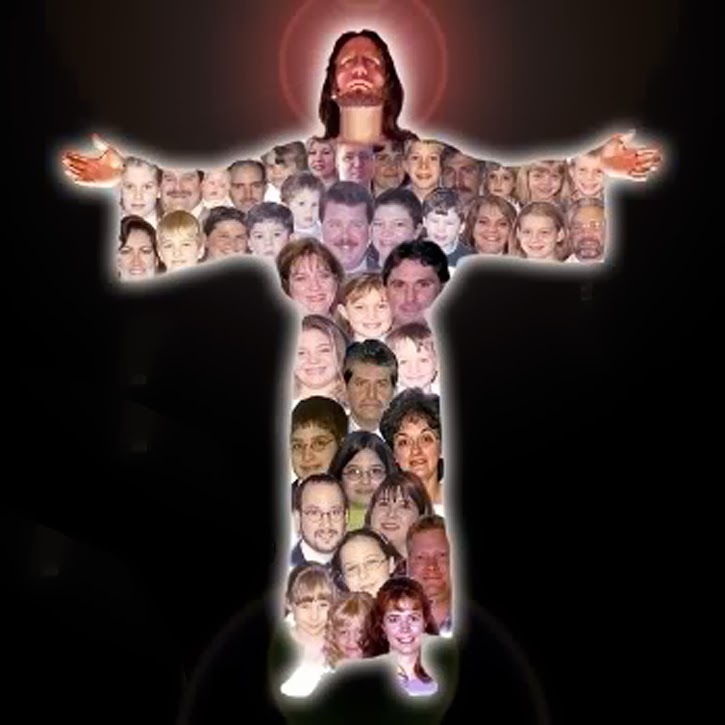

The church as image of the Trinity

Why does the church of Jesus Christ involve this unique kind of unity and diversity of persons that is the gift of God? It is because the church, as a whole, is to bear witness to the Triune God. For centuries, the Orthodox church has realized that the church is an image or icon of the Trinity. It is God’s own unity and distinction as one God in three Persons that is the source and pattern for the life of the church. The church’s unity and diversity are to reflect and bear witness in an earthly way that points to the nature of the Trinity. This is a crucial way in which the church gives glory to God. Its love involves a unity in personal diversity that mirrors God’s tri-personal being—a fellowship and communion of holy love shared by the Father, Son and Holy Spirit.

Thanks Gary,

Very helpful, including the sections on “judgement, proper discipline and discernment, having the goal of restoration in the unity of the Spirit rather than being focused on control and condemnation.” I was just reading Karl Barth on how Jesus’ focus as judge is not primarily to reward some and punish others, but instead “he is the man who creates order and restores what has been destroyed” (Dogmatics in Outline, p.135).