Here is part 11 of an essay from Gary Deddo on the nature of the church and its ministry. For other parts of the essay, click a number: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12. We encourage you to add your thoughts and questions in the “comments” box at the end of each post to get a discussion going. To read the full essay in booklet form, click here. To read the related essay, “Clarifying Our Theological Vision,” click here.

A Brief Theology of the Church

(with a view to equipping the saints for the work of ministry)

by Dr. Gary Deddo

Part 11: GCI’s renewal—unity in the body of Christ

Introduction

In this part of the essay we’ll look at GCI’s renewal, including the reformation of its doctrines, theological foundations and ministry, and how that reformation led to GCI contributing to the unity of the whole body of Christ.

We begin by remembering that the Triune God of love brought his creation into being for the sake of loving fellowship. Created in the image of God, we humans are able to exist in a fellowship of covenant love (agape) with our Creator and each other. However, through Adam and Eve (representing all humanity), the power of evil got a foothold in God’s good creation, reaching down into the roots of human nature. Foreseeing this tragedy, God began to implement his plan to rescue humanity and bring final judgment upon evil. These goals would be achieved by God working in and through the Son of God incarnate as Jesus Christ, and the subsequent ministry of the Holy Spirit in and through the church.

By assuming human nature through the Incarnation, Jesus (our representative and substitute), submitted perfectly to the judgments of God. By his cross he condemned the evil lodged in human nature and on our behalf received God’s gift of reconciliation. We receive all that Christ has done for humanity by participating in the ongoing ministry of the Holy Spirit. Beginning in Acts, the New Testament tells the story of the church’s participation in the Spirit’s ministry (and so the mission of God) during the time stretching from Jesus’ resurrection-ascension and sending of the Holy Spirit to Jesus’ promised return in glory. During this “time between the times” the church is given a down payment (first fruits) of the Spirit so that during this present evil age (when evil has not yet fully passed away and the kingdom is not yet fully manifested) the church can embody signs of the coming fullness of Christ’s triumphant reign in a new heaven and new earth.

As the church waits in hope for the age to come, it grows up into Christ, sharing in his glorified humanity. During this time, the Spirit frees and enables the church to worship God, witness to Christ and his coming kingdom, and participate in his mission to take the gospel to the far corners of the earth as God, by the Spirit, draws all people to himself. As God’s ambassadors of reconciliation, the church has the privilege of sharing in God’s redemptive mission, so that all might be reconciled to God.

In leading the church on this mission, the Spirit works personally, particularly and dynamically and to a large degree mysteriously and unpredictably. The Holy Spirit does not minister in a generalized, predictable, impersonal or generic way. The Spirit meets the church in time and space in the particularities of its social, cultural, economic, political and historical situations. Though consisting of many individuals, congregations and groups of congregations (denominations), the church is essentially one as the apostle Paul notes:

There is one body and one Spirit—just as you were called to the one hope that belongs to your call—one Lord, one faith, one baptism, one God and Father of all, who is over all and through all and in all. But grace was given to each one of us according to the measure of Christ’s gift. (Eph. 4:4-5 ESV)

Reformation of GCI’s doctrines and theological foundations

With the apostle Paul, GCI acknowledges that the church lives in fellowship with its one Lord, Jesus Christ, the Living Word. It does so in accordance with the written word (Scripture), which has been bequeathed to the church by the apostles and prophets appointed by the Lord.

With the apostle Paul, GCI acknowledges that the church lives in fellowship with its one Lord, Jesus Christ, the Living Word. It does so in accordance with the written word (Scripture), which has been bequeathed to the church by the apostles and prophets appointed by the Lord.

Christ’s working (through the written word and by his one Spirit) sparked within GCI (WCG at the time) a movement of renewal and reformation that began nearly 30 years ago. That movement, which involved radical repentance and change, resulted in significant “pruning” as many people resisted the changes that placed Jesus at the center of the center, thus displacing any thought that we somehow “qualify” ourselves for entrance into the kingdom of God. Those remaining with the denomination affirmed the priority of the new covenant in Christ, and the centrality of the person and work of Christ to bring to humanity the unconditioned grace of God. With this renewal of GCI’s Christology came a new recognition of the Holy Spirit being the third person of the Trinity. As a result, GCI rejected its previous anti-Trinitarian stance to embrace the historic, orthodox Christian faith.

GCI’s reformed doctrines and fundamental theology formed the foundation of GCI’s new life in Christ and the basis of its testimony to the grace of God including God’s particular work among us by his word and Spirit. This renewal highlighted for GCI the important truth that Jesus is the key to understanding all of Holy Scripture. It also directed us into a personal and dynamic relationship with God through Jesus Christ.

GCI’s miraculous renewal amounted to Jesus becoming the center of its belief and practice. Re-centered in this way, GCI ceased being off-center. None of this would have happened had GCI’s leaders not been allowed and encouraged to consider Holy Scripture, especially the New Testament, in careful detail and with a proper interpretive approach that matched the nature and purpose of Scripture. Also instrumental in this renewal was consultation with other members (contemporary and ancient) of the body of Christ outside GCI, seeking their understandings of Scripture, doctrines and theology.

GCI’s renewal involved repentance (metanoia) of mind regarding the nature and character of the triune God and his relationship with human beings. The change of thinking was so significant that GCI’s entire doctrinal basis as a church was rewritten as its former doctrinal system (Armstrongism) was abandoned as being aberrant. Though in GCI we know we are not saved by our doctrinal statements or theological orientation, we know well that bad (non-orthodox) doctrines and theology can take us far from a relationship with God that accords with God’s own revelation. Therefore we are very careful to evaluate our doctrinal statements and the theological foundations they are built on, embracing what is good and faithful and rejecting what is not. This means that GCI is deeply committed to biblical and theological study and clarity, leading to a theologically grounded expression of its worship and practice. As a result, GCI devotes many of its denominational resources to understanding and teaching sound doctrines and theology. Through its online videos, written articles and a three-part online 40 Days of Discipleship course, GCI provides ample assistance to all members and others who might be interested.

GCI also provides academic courses through its two institutions of higher education. Ambassador College of Christian Ministry (ACCM) offers a curriculum accessible to all at the undergraduate level and confers a certificate of completion recognized throughout GCI. Grace Communion Seminary (GCS) offers graduate level formal instruction (and currently grants two masters degrees) designed for pastors, other elders, ministry leaders and denominational administrators-leaders. GCS is accredited by the Distance Education Accrediting Commission (DEAC) recognized by the US Department of Education.

That GCI provides these educational institutions is a recognition of the high value GCI places on biblical and theological studies along with pastoral training for the life of its congregations. Though some say that theology is just “head knowledge,” GCI is a living witness to the reality that head and heart are not at odds—they mutually contribute to an integrated Christian life, both individually and collectively. Without “head knowledge,” GCI would be stuck in the flawed beliefs and practices of its past. In God’s economy, love and truth are woven together, not at odds in a tug-of-war. Faithful theology leads to doxology (praise of God). Rather than detracting from worship, doctrinal expression grounded on faithful theological foundations enriches it.

The testimony of GCI is that faithful biblical studies coupled with careful theological reflection is a spiritual discipline that is essential to the spiritual health of the church and the fulfillment of its purpose. Because we are to love God with all we are: heart, soul, mind and strength, neglecting the life of the mind is a grave error—one that opens the church to misguided and even false teaching. The life of the mind moved and disciplined by a living faith in Jesus Christ and informed by Scripture, yields not intellectual pride, but a growing faith and a humble understanding of the deep mysteries of the grace of our Triune God. This Spirit-led life of the mind helps us better communicate the gospel of Jesus Christ in whatever contexts our witness is given.

Leading to communion with the larger body of Christ

GCI’s doctrinal and theological renewal and reformation brought it into communion not only with the Triune God, but with other members of the body of Christ both contemporary and ancient. It turned out that “the one true church” had other members—ones GCI (then WCG) formerly refused to acknowledge due to its formerly eccentric doctrines that alienated WCG from the larger body of Christ. GCI now sees that it shares with all the members of the one (whole) body of Christ a common lived faith and corresponding central (core) doctrines.

GCI affirms the faithful testimony to Christ and the God of the Bible given by the Apostle’s Creed of the second century, the Nicene Creed of 381, the Chalcedonian Definition of 451, and the Athanasian Creed of the 5th century. These creeds serve as secondary guidelines for GCI preaching, teaching and counseling. That we accept them as doctrinally sound, theologically faithful and spiritually edifying indicates our standing with other orthodox churches and denominations in the stream of historical orthodoxy, which summarizes the apostolic faith that was “once for all entrusted to the saints” (Jude 1:3). Along with other churches, GCI can be described as biblical, evangelical (focused on Jesus and his gospel) and historically orthodox (believing what the whole church has believed, starting with the first apostles).

Our Christ-centered doctrine

GCI’s renewal and reformation took place around the center of the center of biblical revelation—Jesus Christ. Our testimony is thus not to ourselves, but to Christ, the center to which we became spiritually reoriented and renewed by the grace of God. A key reminder to us of that center is our Statement of Beliefs, which stands as a doctrinal testimony to the renewal of our faith by the Spirit and according to Scripture. This document serves as a practical norm for GCI and for all who might join with us, in that it directs our attention to the final and unsurpassable written norm (Scripture) given us by the grace of God and through the ministry of the Holy Spirit—the Spirit who, in grace, directed us back to Scripture and in doing so led us to start over again doctrinally.

Our Statement of Beliefs enables us to bear a corporate witness in worship and mission in harmonious cooperation throughout GCI. Upon ordination, our elders (most who serve as pastors), are required to accept this practical standard and conduct their ministry in conformity to it. Those who cannot do so may be sincere and legitimate followers of Jesus Christ, but we do not regard them as being called to serve as leaders within GCI.

Our incarnational Trinitarian theology

Having changed individual doctrines, GCI’s renewal then spread to the reformation of the theological foundations that undergird its doctrinal statements. The theology we embraced recognized that the central question answered by biblical revelation is the Who? question. From beginning to end, the Bible is designed to tell us who God is—revealing his character, nature, mind, heart and purpose so that we might have faith, hope and love for God and enter into true worship in Spirit and in Truth.

The Who? question was fully and finally asked and answered, once and for all, by God himself in the person of Jesus Christ. Acknowledging and embracing this truth, GCI’s theological foundations became fully Christ-centered, which means they became incarnational and Trinitarian. As a result, we embrace what we refer to as “incarnational Trinitarian theology,” holding to a “Trinitarian faith” and “Trinitarian vision” centered on the nature and character of God revealed in Jesus Christ.

To say incarnational is a way of affirming that Jesus Christ, born of Mary in Bethlehem, is the eternal Son of God who, without ceasing to be divine, assumed a real and complete human existence—he became incarnate in time and space and in flesh and blood. As Immanuel (God with us), Jesus was crucified, raised and ascended for us and our salvation. He is the one who fulfilled for us the old covenant by establishing the new covenant in his flesh and blood (in his human nature and form). The term incarnational fills out what we mean by being Christ-centered (along with gospel-focused and thus evangelical).

To say Trinitarian is a way of affirming the orthodox doctrine of the Trinity, which teaches what Jesus revealed (as recorded and summarized by the apostles), namely that the one God is an eternal communion of divine and holy love among the three equally divine Persons: the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit. The doctrine of the Trinity states that God is one in Being and three in Persons, and that our salvation involves the joint working of all three divine Persons as one Savior God.

United within GCI in doctrine, theology and mission

Though there are limitations among our members due to age, educational background and ability, we believe that all who are called by the Spirit to be in fellowship with GCI will share with us in being biblical, evangelical (Christ and new-covenant centered) and historically orthodox. They will sense that the Spirit, by the written word, has led them to understand that our Statement of Beliefs is a faithful and practical norm for grasping the central truth and reality of Scripture and for living in harmony with those already in GCI who affirm and uphold it. They also will feel called to participate with us in ministry and mission on the basis of our doctrines and theology—wanting to pass along to the rest of the body of Christ and to the world, the lessons we have learned and the truths we have come to recognize. There will be a shared sense that these doctrinal and theological concerns faithfully form the shape and focus of our calling to join together in the renewing ministry of the triune God.

Implications for unity with the larger body of Christ

GCI is committed to seeking unity in the body of Christ, avoiding contributing to theological divisiveness by emphasizing what we have in common—the core of the Christian faith, worship and practice. We thus seek to major on the majors—keeping what is less important secondary. The major concerns for us in ministry are those indicated by our Statement of Beliefs and the official denominational writings defining our incarnational Trinitarian theological foundations. In that way, we seek to stay focused on teaching and otherwise helping people understand the gospel that tells of the grace of God in Jesus Christ our Lord.

As we seek unity with other Christians, we do not expect exact agreement with our doctrinal statements, though we do expect that they will affirm the theological foundations upon which are doctrines are built, namely, the biblical basis for what we teach, acknowledging that our core teachings bear witness to the same revealed reality as their statements do, and more particularly that they align with the core teachings of the apostolic faith and worship. Though our doctrinal statements and theirs might differ somewhat at the periphery in terms of what should be included as major or regarded as minor, there should be significant overlap of what is major. We would agree, for example, that what the Apostle’s Creed teaches is major, being a faithful summary of the core doctrines of the Christian faith.

However, there will be times when what we and others teach as foundational will not be in agreement. Sometimes those differences will be only ones of emphasis, but at other times the differences will be significant due to the fact that our respective emphases and particular doctrines are grounded on different theological foundations.

In the church today there are teachers, churches, para-church ministries, parts (factions) of denominations, and whole denominations that refer to Jesus yet do not teach the truths contained in historical orthodoxy, including upholding the authority of the Bible in all matters of faith and practice. Due to their heterodox teachings and practices, GCI would have only a limited ability to worship with them or cooperate with them in ministry in significant ways. However, we do not approach them with harsh judgment, arrogance or self-righteousness. Instead, where we corporately discern the possibility of fruitful engagement, we seek dialogue. If after significant interaction and mutual understanding is achieved there remains significant and fundamental disagreement, there may come a time for us to offer a compassionate warning, and there likely will be only limited ways in which we can meaningfully cooperate in ministry.

GCI’s denominational leaders and local church pastors have the responsibility to offer such compassionate warnings when false teaching arises within their spheres of responsibility. In giving these warnings, we do not condemn, but hold out in trust the testimony concerning what we have come to believe as a witness for them to consider. In situations where church discipline is called for, it will be exercised in hope, trusting they will someday (if not now) come to see that what we affirm as true to Christian faith and practice is a faithful witness to the God revealed in Jesus Christ according to Scripture. In all cases, we trust that God is at work to bring all to spiritual maturity, to the unity of the faith, and so we do our part to assist in that process.

Two very different approaches to church unity

Though GCI is committed to working toward unity in the body of Christ, there is an unhelpful way (called human-centered relativism) and a helpful way (called Christ-centered realism) to pursue that unity. Let’s look at both.

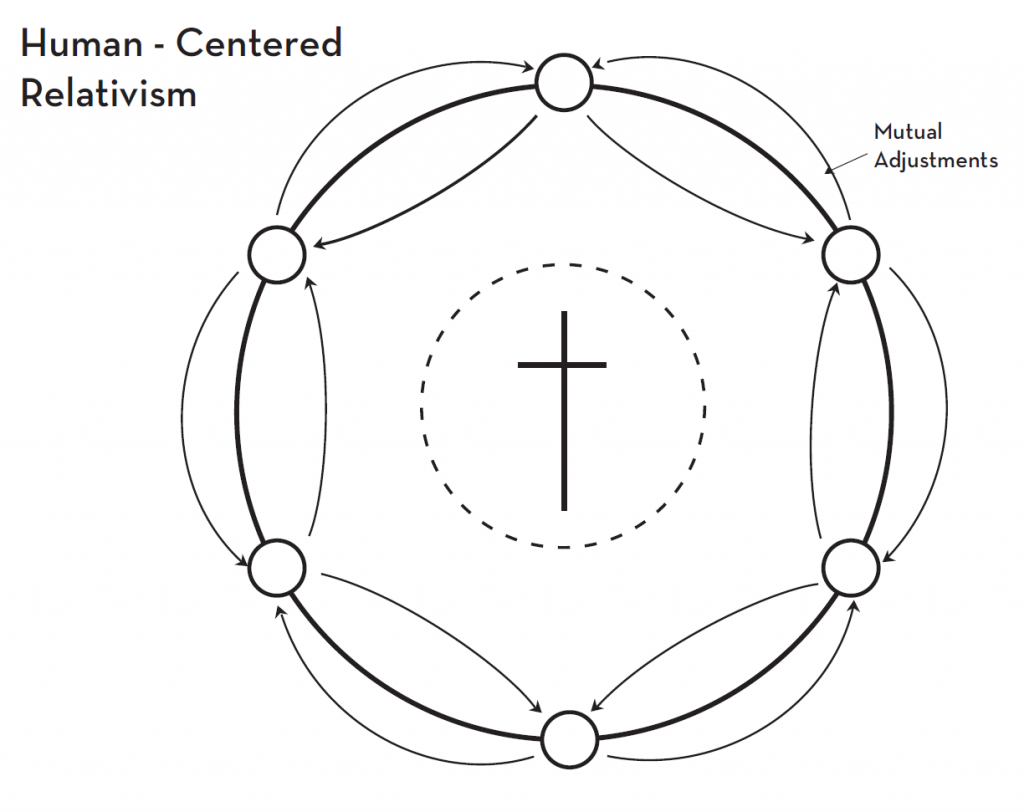

1. Human-centered relativism

A currently popular (modern) way of seeking unity is referred to as human-centered relativism (diagram 1). It means first dialoging with people with whom we differ, then deciding how much to make mutual adjustments to each other in order to “come together.” Doing so involves making certain compromises with the other so as to minimize differences, or, alternatively to ignore the differences or turn what was considered a major concern into a minor one so as to be able to claim some kind of “lowest common denominator” unity. The aim is to achieve some kind of ideal unity through compromise and mutual adjustment, ignoring or devaluing any differences.

Diagram 1

Notes on diagram 1: The large circle in the diagram above represents the whole body of Christ (although it may turn out that there is little to no reason to believe that some we might dialogue with are centered on the biblical revelation of God in Christ according to Scripture at all, and therefore are not meaningfully a part of the body of Christ). The small circles on the circumference represent the various members of the one church. Note how these members are represented as somewhat separated, not only because of organizational or geographical distance, but because of somewhat differing understandings (theories) concerning things like biblical inerrancy, biblical authority, explanations of the Atonement, along with other ethical beliefs and practices.

At the center of the diagram is Jesus Christ (represented by the cross). It is his church, but in this model, he is for the most part sectioned off—remaining at a “deistic distance” (note the dotted line around the cross). This model assumes, wrongly, that we do not have any access to Christ and his Word and Spirit that can serve sufficiently as a unifying authority. It is likewise assumed that Jesus with his Word and Spirit do not have sufficient reality and objectivity to orient and correct our relative understandings and thus bring unity to his body, the church.

In this model, the only option left is to interact with one another, indicated by the reciprocal arrows between the smaller circles and the lack of arrows indicating interaction with Jesus Christ and his Word and Spirit. As a result, in order to reduce friction and so experience some kind of unity, the only option is to mutually adjust to each other and in doing so move closer to each other on the perimeter. If that option fails, one must either give up or continue to emphasize the differences with each party contending for their own view and thus dismissing the views of others as relative and therefore not binding. Oddly enough, this approach to unity in the end absolutizes one’s own foregone conclusions and leads most often to battles of attrition in hopes of wearing down those who disagree, or to making a move toward autonomy (church splits!). These are the unfortunate results of a human-centered (prescriptive) relativism. Such an approach is flawed in foundational theological ways.

Human-centered relativism typically assumes a kind of normative relativism based on several assumptions:

- no one can bear witness to the truth better than anyone else

- the truth or reality to which we would like to have a common witness is not available to us in any way that can bear on our unity

- there is not sufficient reality or objectivity to correct us and provide us significant unity—God’s revelation is not sufficient for this

Given the assumptions of this model, doctrinal and ethical positions can be true only for individuals or isolated groups. They have no import or bearing on others. Assuming that we cannot know the truth to a degree that would amount to a free and faithful witness, all we can do is listen to each other and mutually compromise to one another. According to this model, all norms are relative to one another with none more faithful than others to the truth and reality of God and God’s revelation.

Though this model is quite prevalent in our day (particularly in the West), it is quite foreign to the New Testament. It represents a false humility, a failure of nerve to faithfully seek the truth and understanding in biblical revelation. It is a gross underestimation of what God can and has done through his Word. Furthermore, it does not produce a unity that informs and guides a common faith, hope and love, and a common ministry. It collapses into a vacuous and content-less relativism or into its own absolutism—declaring that no one has a faithful witness and no one ever can (and not even God can do anything about it!). This is what has been called a prescriptive relativism.

On the basis of this model, those who offer a humble witness to the truth according to God’s revelation are dismissed and rejected! This has happened many times in the West, where the limits of humanity overrule the grace of God, and become substitute norms that rule out any real knowledge of God and faithful witness to God and to his ways. Scripture (and the working of the Holy Spirit in, by and through Scripture) is rendered impotent and irrelevant. The so-called humility of human limitation has arrogantly dismissed the ability of God to make his voice known—to make himself known! This perspective turns human humility into an arrogant declaration about what God can and cannot do—into a total, universal, invincible theological declaration and doctrine. This is the height of human arrogance in the guise of modern relativistic humility! This model of unity does not, in fact, operate on the basis God revealed in Jesus Christ according to Scripture as its living center. Rather each individual or group serves as a center to itself and justifies that position by claiming there is no other option and that others who believe there is an option (Christological realism) are deceiving themselves. GCI rejects this model.

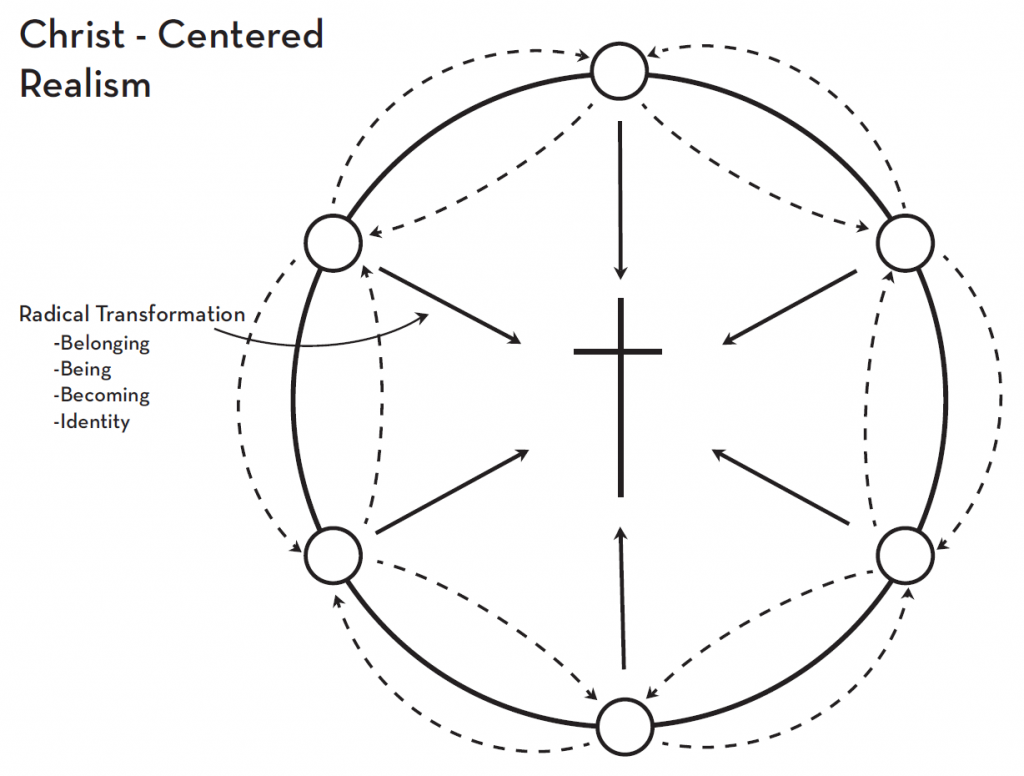

2. Christ-centered realism

If we reject human-centered relativism, what is left? The answer is Christ-centered realism (diagram 2). This model does not mean refusing to listen to and interact with others if and when there are differences. Instead, it means respectfully engaging with those who disagree with us to discover the truth and to bear a more faithful witness to it. This approach is based on the belief and conviction that God and his Word and the working of his Spirit can be accessible and sufficiently objective. This approach assumes that by grace we have access to Jesus Christ by his Word and Spirit, thus providing a reality and objectivity that can inform all the members of the body of Christ, enabling them to become more and more faithful in their doctrines and practices to point to the truth and reality of who Jesus is and who we are in him.

Diagram 2

Notes on diagram 2: Note in this diagram that there is no circle around Jesus Christ that sections him off. Moreover, there are arrows of interaction with Christ and his revelation by the grace of the Spirit. This model does not assume that there are no relative factors involved in our coming to see, hear and understand and so believe in Jesus Christ. The small circles on the perimeter (representing congregations and denominations) are still somewhat separated from each other by these relative factors (background, social setting, experience, language, history, geography, etc.), thus there is still a need for the various members to interact with one another. However, their relative positions on the circumference do not have normative status—their interactions are relative, not absolute, since they are not attempting to mutually adjust to one another. Thus the arrows between the smaller circles are dotted. These interactions are for the sake of becoming as faithful as can be in bearing witness to and adjusting to the Center, the Living Lord according to his Word and Spirit. The lines directed to this Center are solid.

This model allows for a descriptive relativism but denies a prescriptive relativism since there is real contact and interaction with the one who is absolute in every descriptively relative human situation. We are to move “closer” to Christ, in greater conformity to his Word. As we do, we grow closer to one another, just as Paul anticipated:

The gifts he gave were that some would be apostles, some prophets, some evangelists, some pastors and teachers, to equip the saints for the work of ministry, for building up the body of Christ, until all of us come to the unity of the faith and of the knowledge of the Son of God, to maturity, to the measure of the full stature of Christ. We must no longer be children, tossed to and fro and blown about by every wind of doctrine, by people’s trickery, by their craftiness in deceitful scheming. But speaking the truth in love, we must grow up in every way into him who is the head, into Christ, from whom the whole body, joined and knit together by every ligament with which it is equipped, as each part is working properly, promotes the body’s growth in building itself up in love. (Eph. 4: 11-16 NRSV)

Because we are at different places on the perimeter, each member may have to adjust in different ways around or towards the center—perhaps moving in opposite directions at time to draw closer to Christ and so gain a more faithful witness to him. One church may be too legalistic. Another may be tipping toward antinomianism. One may be overly emphasizing the gathered community, while another the missional aspects of ministry. One may need to correct their understanding of sexual ethics. Another may need to deal with its preoccupation with materialistic gain. The relative is not denied in this model, but the relative is relative not just to others and their relativities, but to the Absolute—Jesus Christ and his Word and Spirit with whom we have real contact and relationship that can draw us closer to him. As we grow in conformity to him and his ways, we draw closer one to another. In this growth, Jesus Christ serves as the cornerstone of the whole of the church and all of its individual members built on him and the foundation of the apostolic faith.

Christ-centered realism begins with and proceeds on a fundamental trust that God can deal with human limits and has the motive and capacity to unite us to him so that we might have a common witness to the same God. It embraces the truth that God can (and does) provide a true knowledge of him that brings about a common faith, hope and love for him, enabling his people to have a common witness to the truth of God. Though that truth always exceeds our ability to perfectly describe it, it can (and does) make use of our doctrines and ethical standards.

Through a process of discernment grounded in the objective truth of God, we assist one another to accurately hear and come to some understanding as to the content of that revealed truth. We listen to each other to help us all listen better to the Word of God. We then make adjustments—not to each other, but to the truth as it is in Jesus, who is the Truth. The norm, standard and criterion in this discussion remains at all times the revelation of God that is available to us in his written word, which the Holy Spirit enables us to hear. Thus our unity is sought and established not essentially in our doctrines about Jesus, but by adherence to Jesus himself in accordance with his word (Scripture) and Spirit.

Our respective doctrines will be adjusted and appreciated for how they bear witness to one and the same reality in the same way that Scripture does with final and unsurpassable authority. In this approach there is a recognition that there is but one body, one faith and one Spirit, and we are all called to bear witness to that with our doctrines as best we can. We remain open to the assistance of others, both ancient and contemporary, who aim to do the same thing.

Those who share this approach may experience and bear witness to the actual and real unity that there is in Christ Jesus and find ways to joyfully and freely cooperate even if there is not complete uniformity in doctrinal statements of belief. That is because they share in making Jesus Christ the true, actual and real cornerstone of their faith and practice according to the written witness of the apostles and prophets that Jesus assigned to be his authoritative interpreters.

Conclusion

We understand that God has renewed GCI so that we might participate actively in his mission to the world. Doing so involves bearing witness to that unity with the rest of the body of Christ wherever possible. However, there are obstacles to that unity, and practically speaking, those individuals and denominations that utilize an absolutely relative approach to seeking unity will be of little help to us in achieving that unity. We will pray for them and we are willing to dialogue with them. But we can expect little fruitful collaborative effort in seeking with them the unity found in Jesus Christ according to his self-revelation through the apostolic witness. What we can do is hold out our testimony to what God has done in transforming us as a witness given, trusting that they will one day come to see that there is a far more faithful way to seek the unity of the church of Jesus Christ than mutual adjustment to each other’s relative understandings. We leave the result and its timing to the living God.

The whole of the New Testament affirms, and we have learned through often-painful experience, that by the grace of God and through his Word and Spirit, we can have enthusiasm and conviction without arrogance or self-righteousness. That is because we are enthusiastic and have conviction not about ourselves, but about the God revealed in Jesus Christ. It assumes that God can enable his people to have a knowledge of God through his revelation—one that yields life-giving faith, hope and love for God. It also assumes that the unity of the body of Christ is not in ourselves, but in Christ, and that we can contribute to maintaining that unity, which is the gift of the Spirit. We share in the unity of the body of Christ and in the mission of Christ when we pass on what we have received and look to find others who will also pass on what we have given them, just as Paul taught Timothy and Titus to do (2 Tim. 2:2; Titus 1:9). Doing so is GCI’s calling—one that involves living in faithful relationship with our Triune God, bearing faithful witness to the whole of the church and in its mission to the world.