Dear Brothers and Sisters,

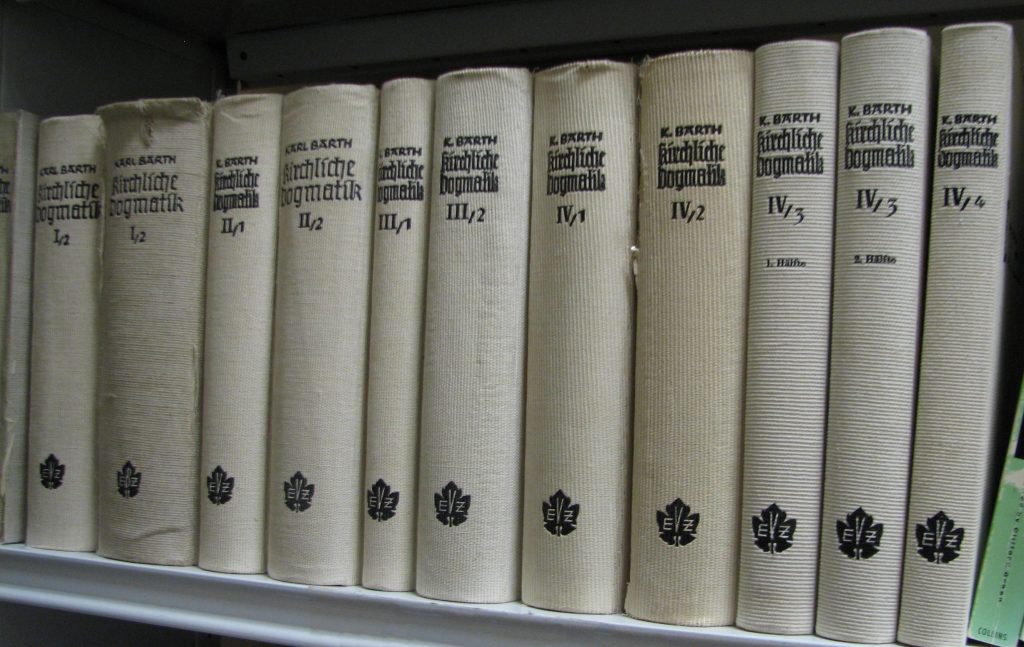

Of all the resources I’ve used in studying theology, the most complex one, no doubt, is Church Dogmatics (CD)—Karl Barth’s opus magnum, which takes up nearly two feet of my bookshelf. A few have joked with me that they are waiting for the Reader’s Digest version!

Reading CD is a rather daunting undertaking. Barth’s sentences are long, complex and densely-packed. Moreover, to understand what he says on a given topic, you must recall related concepts that he has addressed in the earlier volumes, and then recognize that he is qualifying and clarifying as he proceeds from one volume of CD to the next. As a result, Barth is often misunderstood.

Despite these challenges, I find many of Barth’s insights in CD (and in his other writings) to be truly astounding. I’m particularly fascinated with his perspective on evil, which, as I will explain in this letter, he views as a paradox. By doing so, Barth avoids the unfortunate dualistic approach to evil that is characteristic of many books on theology.

Barth’s dialectical method

In CD and his other writings, Barth approached theology knowing that God is not a creature, and thus cannot be understood in terms of creaturely experience and created realities. Nevertheless, God wanting us to know him, revealed himself to us in human form, and spoke to us with human language. But because human language has limits, speaking faithfully about God will sometimes require that we say two different (even opposing) things at the same time in order to accurately account for God’s transcendent reality. This is so because neither statement alone would be sufficient to convey the full truth. Pointing to the truth of God would, in such instances, require holding two distinct claims despite the tension between them. This approach to theology, for which Barth is well known, is called the “dialectical method.”

Examples of seemingly irreconcilable statements held together (in tension) by the dialectical method include the statements “humans are in God’s image” alongside “all humanity fell from its created state of glory.” Another pair of statements is that, in Jesus, “we are masters of all things,” yet, as fallen creatures, “we are slaves to all things.” Barth understood that there is no way to perfectly resolve these rational tensions without turning God into a creature and thus distorting the biblical witness to the God who is revealed in Jesus Christ. Therefore, Barth uses the dialectical method to uphold both statements (affirmations) despite the apparent tensions between them.

Evil—much ado about nothing

Using the dialectical method to examine the topic of evil, Barth finds that evil must be understood as both not something and not nothing. Accordingly, he refers to evil as “nothingness” (Das Nichtige in German). He goes on to describe evil as a force that threatens to corrupt and destroy God’s good creation. Nevertheless, he also sees concern about evil as (to borrow a phrase from Shakespeare) “much ado about nothing.” On the one hand, evil (nothingness) is “that which God does not will,” but on the other hand (and here comes the dialectical tension) Jesus Christ overcame evil as something that truly needed to be undone. Therefore, what Jesus overcame must have real existence of some sort, though its existence, when compared to the will of God, is a bare (shadowy, ephemeral) one, so that, in the end, evil cannot and will not exist at all.

Barth is thus proclaiming that to think biblically about evil, we must understand that because it exists in a way that is wholly in contradiction to God’s eternal, set will, and because it has been decisively conquered by Jesus, it is correctly understood only as “nothingness.” Barth is not playing word-games here—he’s saying that evil is almost nothing and can only lead to being absolutely nothing. To make his point, he must stretch human language to its limits. In doing so, he helps us understand evil, in the light of Christ, for what it actually is—“nothingness” (that which is next to nothing).

Barth explains that this nothingness is utterly distinct from both Creator and creation, representing the inexplicable work of the adversary with whom no compromise is possible. So (and stay with me now to the end of a long sentence), we are left with the nothingness being something that is all but absolutely nothing, and, for a time, this nothingness brings corruption and chaos to the good order of creation, resisting as it does the coming kingdom of God. Wait a minute—nothingness bringing corruption and chaos to something? Yes, though hard to grasp, let this statement sink in. God, who created something out of nothing (creatio ex nihilo) did not create the nothingness. Therefore, he is not the creator of evil. However, he is evil’s conqueror.

Evil (nothingness) moves the something of God’s good creation in the opposite direction to what God wills for it. Barth comments:

Any roads leading away from it (the Glory of God’s Eternity) can lead only to utter nothingness, and therefore cannot be roads at all. Since movement away from it is movement into the utter (or absolute) nothingness, there can be no such movement. (CD II.1, p. 629)

Nothingness, Barth continues, is “irrational” and thus “inexplicable” because it is “absolutely without norm or standard.” Evil cannot be explained (rationalized)—there is no good reason for it. There is no “why” to it that can be answered by giving it a good reason or purpose. If a good answer could be provided as to why evil exists, then we would have made evil far less evil and in fact a contributor to some good. We would, with such an answer, be justifying evil.

But evil has no justification. And were it justifiable, because it was needed to contribute to some greater good (i.e. if evil were somehow necessary), then there would be no need for Jesus Christ, because evil would simply justify itself as being needed to contribute to what is good. But that cannot be, for evil itself is completely unjustified—it is what ought not be, and, indeed, has no good reason to be. Evil is what Jesus Christ has overcome.

Jesus—the way out of nothingness

In understanding evil this way, Barth affirms the biblical claim that all people (sinners all) “have become the victims and servants of nothingness, sharing its nature and producing and extending it.” While we all experience evil (nothingness) in our temporal lives, the good news is that we don’t have to suffer forever since God is sovereign over eternity. God has provided a way for us out of the bonds of nothingness, and that way is Jesus Christ, whose humanity begins the new creation.

In Jesus, evil, sin and death are overcome. In Jesus, nothingness meets its reality, and so becomes absolutely nothing. God, in Christ and by the Spirit, limits and conquers the negative aspects of this nothingness that can and have threatened the significance of the existence of the world and the human race within it. Again, to borrow a phrase from Shakespeare (here words spoken by King Lear), “Nothing will come of nothing.”

In Christ, God has given an absolute and uncompromising “No!” to nothingness as an uninvited, unwanted intruder into his good creation. While God did not create nothingness (which was at work in the chaos from the beginning), he will vanquish and conquer it completely. That is a big reason the gospel is good news.

In spite of the difficulty and complexity involved in reading CD, it is rewarding to do so when persistently pursued. I illustrate this by relating a comment from my dear friend, Grace Communion Seminary Professor Dr. John McKenna. He once told me that when he read and understood Barth’s picture of redemption, for the first time in his life (through all the pain, sin and heartache of his past) he felt that God truly loved him—he no longer feared the nothingness. He said it was as if someone had laid hands upon him and healed him. I love that illustration, because I believe the true and miraculous path to our healing comes from realizing that Jesus Christ is the only means of freeing humanity from evil—from the grip of nothingness.

We are reminded daily that we live in a world of injustice, cruelty, pain and suffering—the picture of this present world presented in Scripture. However, the reality is that Jesus has promised to take all this pain and suffering away, leading to a new heaven and new earth at his return. In our modern times, the only philosophical problem of evil that could ever trouble a thinking Christian is some kind of confirmation of a total absence of sin and evil in the world. This is because, paradoxically, the presence of evil in the world proves the validity of Christianity’s claim that there is evil (things that simply ought not to be but somehow do exist), and Christianity’s affirmation that we all need to be rescued from evil but cannot do so ourselves. However, there is real hope because evil has been conquered and a time is coming when God (as he has promised) will wipe away all tears, and there shall be no more death, sorrow, crying, or pain. That which ought not be, will, in the end, not be. In short, evil has no future!

Loving Jesus and his promises,

Joseph Tkach

Wow!Thanks so much Sir!

Thanks Joe, this is a great distillation of Barth’s trademark complex ideas. One question: did Barth consider himself annihilationist ? That those who consistently chose Das Nichtige become Das Nichtige?

Josh, here is Gary Deddo’s response to your comment/question on Joseph Tkach’s article on Barth’s theological perspective on evil:

Barth did not affirm annihilationism. The primary reason seems to be that he avoided speculation derived from logical inferences from what Scripture centered in Christ does reveal. So he remained a hopeful but not a dogmatic (a matter the church could teach as a normative belief) universalist. He would not go further and develop a theory that resolved things, things perhaps inherently unresolvable and certainly not biblically resolved about the ultimate state of every individual creature.

But the fact remains that nothing can exist apart from God and Christ is Lord of all and that evil cannot exist in the same way God’s good exists. So perhaps the best we can say, following something like what CSL seemed to hold, is that those who eternally refused God’s grace, perhaps reaching a point of no return, would eternally be diminished and eternally approach non-existence (like a mathematical asymptote) but never actually reach 0.

Other recommended readings are Donald Bloesch’s Last Things (IVP) Henri Blocher’s Evil and the Cross, and N.T. Wright’s Evil and the Justice of God.

The “Catholic Dictionary” helpfully defines Barth’s Dialectical Theology as “a system of thought… which holds that the main feature of the Christian religion is an inherent opposition among its revealed mysteries. The fundamental opposition, or *dialectic*, is between God and man. Other oppositions, such as time and eternity, finite and infinite, creature and Creator, nature and grace, are derived from the primary conflict. Moreover, dialectical theology claims that these oppositions cannot be reconciled by the human mind. Only God can bridge the gap that separates them.”

In a similar vein, Ben Myers (in a post on the “Faith and Theology” blog at http://www.faith-theology.com/2007/02/explaining-evil.html), notes how author David Bentley Hart (in “The Doors of the Sea”) labels as “morally loathsome” attempts made in many theodicies to justify evil by appealing to its broader meaning in God’s plan. Against such dualisms, Hart argues that “suffering and death—considered in themselves—have no true meaning or purpose at all,” or, as Barth would say, they are “nothingness.” As Hart goes on to explain, “this revelation [of the true nature of evil], in a very real sense, is the most liberating and joyous wisdom that the gospel imparts.”

According to Hart, the Christian faith “denies that… suffering, death, and evil have any ultimate value or spiritual meaning at all.” Instead, he says, “they are cosmic contingencies, ontological shadows, intrinsically devoid of substance or purpose, however much God may—under the conditions of a fallen order—make them the occasions for accomplishing his good ends.” To offer a rational explanation or “justification” of evil is thus to explain what God himself refuses to explain. In Karl Barth’s words, evil is das Nichtige—futility, vanity, emptiness, nothingness. It is that which passes away. It is the absurd nothingness, which God refuses to interpret or explain or endow with meaning. It “is” only in as much as God rejects it utterly. It “exists” only as that which God vanquishes and overcomes in the death of his Son. It is that horror, which is never synthesised or redeemed, but only cast out. It is the shadow of violence which Jesus Christ exposes and expels with the light of his peace. And that, my friends, is truly good news!

I don’t know who first told this story about Dr. Barth, but I have enjoyed using it many times over the years. Dr. Barth was asked by a newspaper religion writer if he could condense the content of his recently-completed CD series on the Bible, to just a few words for the newspaper’s readers. He told the reporter this, “Jesus loves me, this I know, for the Bible tells me so.”

Barth would have done us all a favor by not using the term “nothingness” to define evil. I understand that his selection of wording seeks to emphasize the same concept that C.S. Lewis observed more adroitly, that evil is really the absence or misdirection of good. In Lewis’ view, evil is philosophically insubstantial. But I would observe, pragmatically, evil is something. And Barth has to come back to it being something to explain what Christ overcame. One might ask, if loving someone today is “something”, how can hating someone today not be. If we are not careful with Barth’s difficult and translated semantics we end up with Christ overcoming nothing which is clearly not what Barth intends to say.

The strict separation of God from Barth’s nothingness is also problematical. God is sovereign and is responsible for evil either directly or via agency. He does not cause or create evil but he does license it. Does anyone believe that Satan operates outside of God’s permission? At a minimum we would have to conclude that evil is a tool, many times inexplicable in it use, in God’s hand for achieving his ultimate purposes. This is not joyful to contemplate but empirical evidence supports it, David Bentley Hart to the contrary. Paul seemed to think overcoming evil had meaning and value.

Hi Joe;

Thanks for distilling Dr. Barth “perspective on evil” and I believe I got a whiff of it. Very interesting what he told the reporter, “Jesus loves me,this I know,for the Bible tells me so.” My kind of lingo.

Evils is that which does not make sense.

Joseph Tkach recommends an article on Barth’s theological perspective on evil (includiding the topic of demons at http://postbarthian.com/2016/03/09/believing-in-demons-makes-you-a-little-demonic/.

I enjoy the word play that Barth uses in regards evil as nothingness but something. However I have a question in relation to where the nothingness comes from? In the article its says nothingness is not created, but out of the nothingness (chaos) God does create. This seems to put nothingness on par as always having been. John tells us in the beginning was the Word and the Word was with God and the Word was God. We know in the beginning was Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. Not nothingness. So where did nothingness come from? It can’t be on the same par as God as having not been created, because only God is not created. Even Lucifer is a created being, though he was created as a beautiful angel. Just wondering if the word play of nothingness causes more than just a paradox in regards to where it comes from if it wasn’t created?

Here, from Gary Deddo, on behalf of Joseph Tkach, is a reply to Al Kurzawa’s commment/question:

Barth’s section on “the nothingness” (das nichtige) is long and complicated. Pastor Tkach was getting at just one point. It needs to be said that Barth was not attempting a theodicy (an explanation of why there is evil that exonerated God) or to explain the ultimate source/origin of evil, that is the ultimate “why” of evil. He did not believe that either of these could be achieved or should be attempted since we have little revelation aimed to illuminate that level of explanation. Also since no logical inferences about things of fact are ever necessarily true, one cannot create a string of logical inferences from what is revealed to what is not revealed. Instead, Barth’s task as a dogmatic theologian of the Church was to try and understand how the parts of revelation we do have fit together, since there are apparent inconsistencies or what we call paradoxes. But we must do this without dismissing parts of the full revelation and let the revelation critique our ways of thinking to see if a more faithful understanding can come forth.

And if there is no good understanding we can find, perhaps we can explain why we should expect there not to be a good and faithful explanation. That can be a legitimate theological aim. That too might fall short, but its attempt is not wrong and not necessarily speculative. The theological process of discernment can also result in giving us a focus on what we can understand from the given revelation.

Now, on to your question. So Barth is not attempting to give an explanation for the ultimate origin or why of evil. And he thinks doing so would require unfaithful speculation. So you won’t find that in KB nor would he encourage anyone to attempt to do so on the basis of Scripture or his own theological reflections!

Barth does not affirm that anything exists eternally along with God. That is ruled out by much teaching and insight from the Psalms and Isaiah as well as John 1. While there is some ambiguity in Genesis 1, there is no need to think that “the void” existed eternally along with God and since that is ruled out by John 1, we shouldn’t go there. God is the only thing/one who has aseity, his own existence and is not created. God alone is self-existence, or a the NT puts it, has life in himself.

Another fixed point of revelation is that whatever exists is under the lordship of Jesus Christ. An additional given is that evil has no future—it is vanquished by Jesus Christ. Another important “given” is that all that exists, in one way or another, is dependent upon God, for nothing self-exists, except God. A final “given” of biblical revelation is that Jesus Christ did not come and die and be raised from within creation as one of us for absolutely nothing. So correlated directly with that supreme given, it follows that what Jesus came to deal with is not nothing. It must, in some way be, temporarily, something. And that something in Scripture is given the name of evil, the demonic, what resists God’s good will, his good creation and his good purposes and corrupts God’s good creation including making use of the willful collusion of God’s human creatures to do so.

So then, KB asks this: On such bases, what can we say about evil? What is its nature? Can we say anything by bringing these pieces together that add up to understanding? His answer, most briefly, is that evil is not absolutely nothing (das Nicht), but rather we can say that it is “nothing-ness” that in the end will become absolutely nothing (das Nicht). The “-ness” in English being the suffix that indicates some kind of abstract quality of something, eg. spicyness. But evil cannot be granted anything more than that given all the other “givens” of biblical revelation. It barely exists compared to God and God’s goodness and the goodness of his creation and his ultimate good purposes for it. But it also cannot be given less than that either, on the same basis, it is what Christ overcame and has no future. It does wreak havoc on earth and God is opposed to it, whatever it is.

Another way to sum up KB’s understanding is that evil exists in an entirely different way than God and God’s creation. Christian revelation rules out dualism, two equal and independent opposite transcendent ontological powers. God has no ontological opposite, called evil. Good and evil cannot and do not exist in the same way, even if we use the word “exist” for both. That is very difficult to understand, but in the end it is quite necessary to understand. And that means that we cannot say that God created evil, using “created” in the same way we mean how God created the good creation and has ultimate good purposes for his creation.

So KB will allow that we can say something about the possibility of evil, but not the ultimate origin or the why of evil. Its possibility involves God creating that which is not God and saying both what ought to exist in creation and what ought not to exist in creation and God’s commitment to bless what does exist and to oppose and do away with whatever prevents such to take place. So evil, in that sense, only has a theoretical or hypothetical possibility for a temporary effect upon and within creation. But the possibility of evil is co-terminus with the reality of a good (not evil) creation. The “Yes” and so the “No” of God that is necessary when God speaks about what is not God (that is, creation) opens the door to the “impossible possibility” of evil. That is, evil is that which is all but absolutely impossible and in the end is not possible at all, it will be vanquished. But God’s “No” contemplates that which ought not to be, somehow having some kind of very different, even alien existence compared to his creation.

Humans being moral and spiritual distinct human (created) persons created for fellowship and communion of holy love, not rocks or automatons, but yet being personal created beings who are not divine, have the possibility of misusing or throwing away their freedom to be in relationship with God, and so open the door to evil entering the creation. This does not explain the ultimate origin or “why” of evil, but simply how the almost impossible possibility came into creation and effects it and got a foothold in it. Like a lie.

And so in retrospect the “chaos” of creation in Genesis 1 should not be taken as an eternal reality, much less as an evil that God created. The chaos there has not been understood in Christian theology as being something. God’s creating “out of nothing” means there was absolutely nothing other than God before God created. So the chaos there (at creation) has not been understood as the void/nothing which is indicated in the “created out of nothing” (ex nihilo). So it does not exactly correspond to KB’s “nothingness.” It points to the results of what would happen to God’s creation if God abandoned it or if evil managed to cut it off from God, and of course that result would itself be, well, evil results.

Rather, the chaos represents the theoretical threat, the impossible possibility of evil that God has said “No” to but creation could say “yes” to. It shows that God’s good creation requires God’s holding it in good existence, otherwise it would fall into chaos, disorder and finally, back into absolute nothing (nichte) that is non-existence, not just the chaos of something. And since the existence of creation is good, given it is created and sustained by God for good even eternal purposes, then that which might tempt his good creation or threaten to disconnect God from his creation and so inevitably result in its fall into non-existence, would need to be called evil since it is against God, his purposes and his good creation.

Thus the chaos of Genesis 1 should not be understood as existing the same way as creation, but is where creation would end up if evil had its way, attempting to cut creation off from God’s good upholding and perfecting goodness and grace. It is not a basis for creation, a pre-existing eternal or created “stuff” or “evil” itself, but by contrast shows what God must do to have creation exist, namely giving it form and life and order, meaning and harmony (so that good things exist compared to not existing at all) and what would happen (falling back into non-being) were evil to get its way.

The chaos/void in Genesis then, is better understood to indicate a hypothetical or abstract threat to God’s good creation and so indicates the necessary relationship of God to creation and the danger of that relationship being cut off by what only can be called evil. But it is evil that will, in the end, absolutely not be, but for now has a kind of existence Barth allows we can faithfully call the “nothingness.” Because God is God and his creation can be rescued from evil and nothing can prevent God’s good purposes from being realized, there will be a new heaven and earth. There is a real threat to creation so that it might not have any future at all, but given God’s goodness and grace, instead that which threatens his good creation, evil, has absolutely no future.

That is the best I can do to try and summarize what KB was attempting to share with us in this discussion of the “nothingness.” But yes, there is no answer as to the ultimate origin or why of evil. But the goodness and faithfulness of God comes through as does his warning to us concerning the threat and evil of evil and the victory of God over “it” in which we can participate through Christ and by the Spirit.

Consider reading:

“Facing the Fiend” by Eva Marta Baillie

While I understand what Barth is getting at, his use of terminology is obscuring. An example of nothing, a difficult concept for the human mind, is this: All positive numbers less than zero. This set contains nothing although we might argue that the mathematical principles that underpin the idea suggest that this is only a “logical” nothing.

Nichtige in usage seems to be derived by developing attributes for the concept of nothing (nichts). This is not strictly within the bounds of what you can do with “nothing” logically. Creating an attribute profile, one can say that Nichtige means that which is futile, not worthy of consideration, without significance and without a constructive purpose. But the fault here is that this is like saying that the number 3 is more like zero than the number 22 when in fact 3 and 22 both are profoundly unlike zero. This is because there is a binary opposition between having value and being valueless.

While this all sounds very nerdish, words do have meaning and influence. And there is a perfectly good Biblical word for what Barth is describing. It is the word “vanity”. If he had written that “evil is vanity”, most people would have understood this almost intuitively and without resort to dialectical tension.

Some observations about Gary Deddo’s exposition concerning evil:

1. If we cannot define something, how can we expect our analysis of it will have any validity? By what metric will we measure the success of our analysis?

2. How is chaos in the creation evil? (Here a definition of evil has been assumed.) Chaos has no moral content. Every day entropy is increasing in the universe. Why should anyone regard this as an evil instead of a natural, built-in process that God easily manages?

3. The Bible speaks of evil as if it were not a recondite concept. There is the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil. We are encouraged by Christ to pray daily that we be delivered from evil. It seems that evil (“whatever it is”) more than “barely exists.” It seems, rather, to be a powerful force that shapes reality. And for some people the consequences will be eternal, unless Universalism holds.

4. How is Barth’s viewpoint superior to the traditional Christian view that evil is simply the misbehavior of created sentient beings in the exercise of free will (Calvinists can drop out at this point)? This traditional view seems to fit comfortably the model of evil in the OT and NT.

Here is a comment we received from Peter Lee of McKenney, Texas:

Joe, thank you for expounding Barth’s insight about evil. Whether we will ever get down to ever attempting Barth’s writing is another matter, but we are grateful that you do. Your explanation is indeed insightful and beneficial.

Thank you Gary for taking the time to write in further detail about KB and his thoughts on “nothingness”. A lot to think about but I feel like I have a better idea now of what he was trying to get across. I wasn’t expecting as much on the topic of chaos in Genesis 1 but plenty there to think about as well. In referring back to Joe’s article, the main point is that we know what is to become of evil. So even if we don’t understand the beginning or the “why of evil” the good news is that we know the end result of evil and that is good news worth celebrating. Thanks again for taking the time to write.