Dear Brothers and Sisters,

I became a fan of English author, philologist and poet, J.R.R. Tolkien after reading The Hobbit and its sequel, the epic three-volume novel, The Lord of the Rings. Among other literary achievements, Tolkien in his fantasy books constructed the grammar and vocabulary of at least 15 languages and dialects, the most-developed being the one spoken by his Elves. Though the extent of his literary achievements is amazing, what impresses me most is what lies behind those achievements—Tolkien’s appreciation and love for the goodness of God.

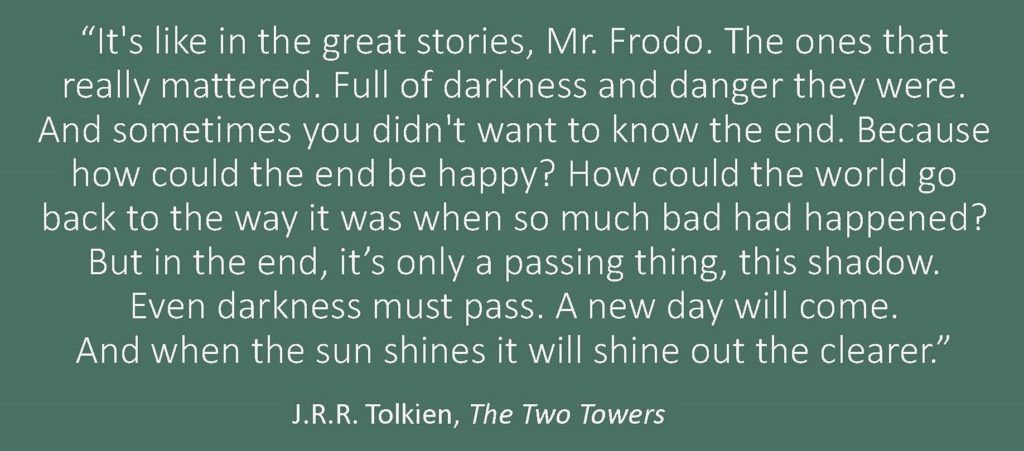

Though he avoided direct references to Christian doctrine in his books, Tolkien pointed people in that direction by connecting fantasy to the realities of the human condition in a fallen world. Who among us hasn’t had to deal with a Troll or two? Who hasn’t found a special place of peace and tranquility? Not only does Tolkien deal with these human realities (along with bravery, sacrifice, hospitality, honor, beauty and love)—he also indirectly points his readers to transcendent realities. For example, in The Two Towers (the second volume in The Lord of the Rings trilogy), Tolkien utilizes the imagery of light breaking into darkness—imagery that mirrors the Light of the World coming into a dark, sin-sick world via the Incarnation.

In one of his letters, Tolkien wrote that, “the incarnation of God is an infinitely greater thing than anything I would dare to write” (Letter 237). Thus, it is no surprise that Tolkien, the great story teller, was enamored with the Incarnation, for it is the greatest story ever told! For the substance and reality of that story, we rely not on Tolkien, but on the writers of the New Testament Gospels like the apostle John, who began his Gospel with these evocative words:

In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God. He was in the beginning with God. All things came into being through him, and without him not one thing came into being. What has come into being in him was life, and the life was the light of all people. The light shines in the darkness, and the darkness did not overcome it. (John 1:1-5, NRSV)

Though Tolkien’s fantasy novels do not tell the complete Christian story, they are full of themes he hoped would prepare people to hear the Christian gospel. What I especially appreciate is the way The Lord of the Rings trilogy points out the reality of good and evil, the power and temptation of sin, and the fact that everyone needs redemption. If you read the trilogy or watch the movies based on it, you’ll encounter dark and heavy moments where good people suffer, and some give in to the darkness of evil. Yet you’ll also find that no matter how far a character might fall, Tolkien shows there is always hope—always opportunity for redemption.

Another thing I like about Tolkien’s stories is the way they refute the dualistic idea of the separation of body and spirit (soul). In pointing to the dynamic unity of body and spirit, Tolkien undermines philosophies (such as naturalism and Gnosticism) that separate body and spirit. In doing so, he indirectly opens a door for his readers to consider that the Incarnation (the union of the uncreated Son of God with created human nature) might be possible. The heroes of his stories represent real people who live as “embodied souls,” and “ensouled bodies” (as Karl Barth put it). Tolkien’s characters appreciate good ale, a simple meal and enduring fellowship, all the while taking seriously the universal obligations of the good, and the real dangers of the evil.

Some people worry that fantasy novels like Tolkien’s risk perverting good theology. But that would be true only if we were to look to such books as sources of theology. The fact of the matter is that they are not. Tolkien never intended his trilogy to be more than a prequel to the biblical gospel. His goal was to point out the questions, problems and challenges in life, not to provide answers that come only through biblical revelation.

Tolkien cleverly directs a secular world away from the naturalism and nihilism that is so prevalent in our world, towards the biblical world of moral meaning and personal relationship with the living God of intervening grace. His overarching message is that no matter what adversity we face in this world with its darkness, a real and transcendent goodness (light) is still present and prevailing. No matter how far astray we might have gone from that light, there is hope of restoration. The overall conclusion of The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings trilogy is that this hope exists no matter what we face. The apostle Paul draws a similar conclusion in his letter to the churches in Rome:

And not only that, but we also boast in our sufferings, knowing that suffering produces endurance, and endurance produces character, and character produces hope, and hope does not disappoint us, because God’s love has been poured into our hearts through the Holy Spirit that has been given to us. (Romans 5:3-5, NRSV)

Tolkien understood a powerful truth, which he pointed to in his writings: The Incarnation is the best story that can be told. We celebrate that story in a special way during the Advent-Christmas season.

I love to tell the story,

Joseph Tkach

You have explained why my love for Tolkien’s writing is justified. Thank you.

Once upon a time, I thought I had gone too far from the light, so now I always like to be reminded there is no such thing, for the light always goes farther than the darkness and overtakes it. You rock Joe.

Hi Joe.

I have been an admirer of Tolkien since I read the Lord of the Rings trilogy in high school, impressed by its spirit of nobility, sacrifice, and defense of what is right and good. When I learned he was one of the Inklings along with C.S.Lewis, my interest only grew. If you haven’t come across it, I recommend Splintered Light: Logos and Language in Tolkien’s World by Verlyn Flieger, Eerdmans, 1983. It is full of insights on the themes of Hobbit, LOR and Silmarillion.

Best wishes.