Dear Brothers and Sisters,

Genesis is perhaps the most debated book in the Bible, largely because its purpose and nature are often misunderstood. Fundamentalists and evolutionists alike claim that Genesis conflicts with science. But Genesis makes no attempt to address many of the questions that are the concern of modern, evolutionary science. The purpose of the creation narratives in Genesis (there are two, as I explain below) is not scientific but theological (with philosophical and religious implications). The creation narratives reveal who the creator God is, what kind of relationship he has with his creation, and his ultimate purpose for his creation. Science has other concerns.

Genesis is perhaps the most debated book in the Bible, largely because its purpose and nature are often misunderstood. Fundamentalists and evolutionists alike claim that Genesis conflicts with science. But Genesis makes no attempt to address many of the questions that are the concern of modern, evolutionary science. The purpose of the creation narratives in Genesis (there are two, as I explain below) is not scientific but theological (with philosophical and religious implications). The creation narratives reveal who the creator God is, what kind of relationship he has with his creation, and his ultimate purpose for his creation. Science has other concerns.

Evolutionary creation?

The creation narratives of Genesis do not give detailed descriptions of the mechanisms involved that explain exactly how creation came about or unfolded. The descriptions are not “scientific” (as we would say today) in that way. But that does not mean they are inaccurate about what they do explain. Unfortunately, many of the scientists in the ongoing debate make claims that are largely philosophical rather than strictly scientific. Scientist Richard Dawkins (one of the so-called new atheists), a vocal contributor to the debate, is a prime example. His arguments, rather than being about material aspects of creation ascertained by the scientific method, are philosophical claims involving speculative logical inferences about God, religion and evil made from selected scientific information. That being said, a right understanding of Genesis does not rule out the possibility that God has (at least in part) used evolutionary processes to advance his creative purposes.

The creation narratives in Genesis leave room for theistic evolution (others prefer the term evolutionary creation), by which God oversees evolutionary processes in bringing about his purposes for creation. God’s oversight of and intervention in his creation comes, ultimately, in and through Jesus Christ. Since Genesis and the rest of Scripture do not specify the means God used (and continues to use) in creating, we are free to adopt the best scientific theories available that do not contradict the theological claims of biblical revelation.

Why the Genesis creation narratives?

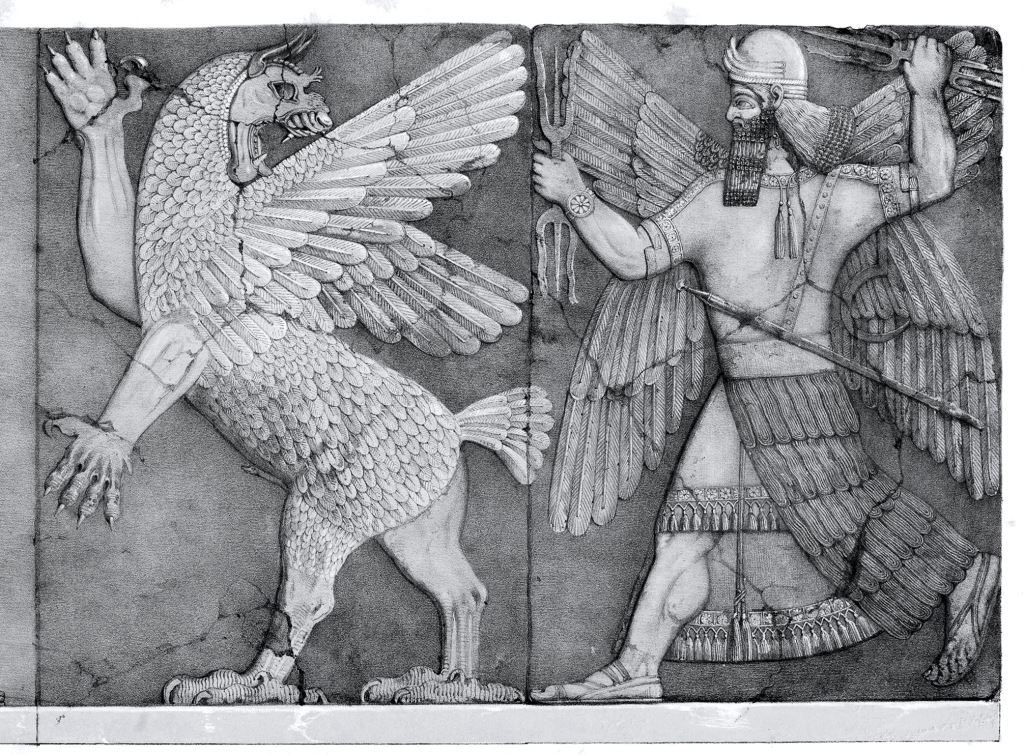

Because the purpose of the Genesis creation narratives is fundamentally theological, they rule out the claims of atheism, polytheism, deism and dualism. In fact, the Genesis creation narratives likely were written to address those who had heard of and possibly believed in the creation myths taught by the polytheistic religions of Babylonia, Akkadia and Egypt. Evidence for this is seen in the many similarities between the Genesis creation accounts and the Babylonian creation myth known as Enûma Eliš. One of those similarities is that both begin with a watery chaos.

Unfortunately, some skeptics go too far in what they make of these similarities, claiming that the author of Genesis merely changed the Babylonian creation myth to make it about the God of Israel. But in making that claim they fail to account for the crucial differences between the biblical and the polytheistic creation narratives. Genesis gives us a theological explanation of who God is quite different than that of the pagan myths. Whereas Genesis tells the story of the creation of humanity by the one God of Israel, Enûma Eliš tells the story of creation through many gods, who in turn give birth to several other gods who grow up to be quite a rowdy bunch (much like humans!).

Concerning the differences between the Genesis creation narratives and the Babylonian creation myth, Victor Hurowitz (in Is the Creation Story Babylonian?), wrote that it is “patently untenable” to speculate that the biblical authors simply took Enûma Eliš and “applied it to YHWH.” [1] As Hurowitz and others have noted, the character and purpose of the one creator God presented in Genesis is entirely different from the gods of the polytheistic creation myths. Consequently the depiction in Genesis of God’s relationship with humans is entirely different than the relationship between the gods and humans depicted in the pagan myths.

Reading Genesis rightly

Adding to the complexity of understanding Genesis is that it contains two creation narratives in its first few chapters. Current debates about Genesis often overlook this, along with three other facts: 1) the creation narratives are small parts of the larger whole of Genesis, 2) the focus of Genesis is not creation but the nation of Israel, 3) Genesis is part of the Pentateuch and the entire Bible, giving it a much larger context than is typically acknowledged.

It’s also important to note that Genesis must be read through ancient eyes rather than modern ones. These different “lenses” assume different things and ask different questions. Reading with ancient eyes requires that we become aware of our modern perspectives that mainly want to know how things work and how to use things for our purposes. Modern “scientific” explanations insist that we don’t need to know anything about any agent involved in creation, but only the mechanisms of the natural world. It also insists that there is no need to know the ultimate purposes of those things that exist—only how to use them for our own ends. In our modern era, these philosophical assumptions determine what constitutes scientific explanation, thus reducing the search for knowledge by asking essentially technological questions.

Reading Genesis rightly also requires that we understand what the original audience expected from stories such as the creation narratives. Ancient readers would not have looked to Genesis to learn how creation works at the natural, material and causal levels. Instead, they would have wanted to know about the agent(s) responsible for creation and its ultimate purpose or destiny.

Rather than trying to make Genesis answer modern, very constricted scientific questions it was not designed to address, we should ask, What questions was Genesis actually designed to answer? Genesis reveals theological truths about the agency behind creation and its purpose. It does this in fairly straightforward ways that do not require logical inferences and speculations about what is written.

For example, no passage of Scripture directly states the age of the universe. Trying to determine the date of creation from the Bible requires interpolating from what the biblical authors say about other things. But such interpolations (logical inferences) do not lead to truth. That is why the church, when it began to debate the improper question of the age of the universe, was unable to come to agreement. Those who contributed to the debate offered only unprovable theories based on unprovable assumptions, generated by logical inferences using biblical information provided for very different purposes! An example is the work of Bishop James Ussher who claimed to have calculated the exact date of creation based on inferences from biblical genealogies.

Another key issue in reading Genesis rightly is being able to identify the literary genre of the text. Tremper Longman III, professor of biblical studies at Westmont College, makes that point in his book, How to Read Genesis: “No reading of the book [of Genesis] can proceed without making a genre identification. Most people do it without reflection, a dangerous procedure since an error in this area results in fundamental misunderstanding of the book’s message” (p. 23).

Ultimately, the only way to rightly read Genesis is to read it through the “lens” of Jesus Christ—carefully accounting for his life, death, resurrection and ascension. In his Gospel, Luke tells us that, “beginning with Moses and all the Prophets, [Jesus] explained to [his followers] what was said in all the Scriptures concerning himself” (Luke 24:27). Jesus then said to them, “‘This is what I told you while I was still with you: Everything must be fulfilled that is written about me in the Law of Moses, the Prophets and the Psalms” (Luke 24:44). Luke then tells us that Jesus “opened their minds so they could understand the Scriptures” (Luke 24:45). It is Jesus—who he is and what he has done—that informs our understanding of Genesis as well as the rest of the Old Testament (and, indeed, the whole of Scripture).

The importance of seeing the whole picture

In Genesis: the Movie, Episcopal priest and scholar Robert Farrar Capon explains the book’s title and purpose:

In Genesis: the Movie, Episcopal priest and scholar Robert Farrar Capon explains the book’s title and purpose:

[My purpose is to] help people stop reading the Bible as if it were a manual of instruction in religion or spirituality or morality or anything else and to start watching it as a film, presented to you by the Holy Spirit, who is the movie director. When you watch a movie, you don’t stop 10 minutes into the film and try to decide what it means. You cannot fairly say anything about the movie until you have seen the whole movie and hold it in your mind as an entirety—as a whole piece. And that is what needs to be done with the Bible. It has to be seen as one thing. So I’d like people to see biblical inspiration, not as a matter of word-by-word inspiration, but as scenes in the movie the way the director wants to show it to you, that is, scene-by-scene.

I think Capon is on to something here. If we don’t see the whole picture of the Bible, it’s easy to derive inaccurate meanings from passages that we are pulling out of the context of that one “movie.” It’s when we see what the Holy Spirit as the movie director is doing that we pick up the clues woven into the text. Capon’s book helps us understand not only the purpose of the book of Genesis, but how the whole of Scripture is integrated around the core of God’s ultimate plan of redemption in Jesus Christ.

Reading Genesis in the light of Jesus

I’m glad to say that my dear friend John McKenna (pictured at right) is writing a book that will offer important incarnational, Trinitarian perspective on Genesis. It will explain that Moses, the author of Genesis, was the great prophet who lived at the beginning of Israel’s history. It will note parallels between Moses and Jesus, referencing, for example, Deuteronomy 18:15 (KJV): “The LORD thy God will raise up unto thee a Prophet from the midst of thee, of thy brethren, like unto me; unto him ye shall hearken.” Recognizing Moses as a prophet significantly impacts how we read Genesis.

I’m glad to say that my dear friend John McKenna (pictured at right) is writing a book that will offer important incarnational, Trinitarian perspective on Genesis. It will explain that Moses, the author of Genesis, was the great prophet who lived at the beginning of Israel’s history. It will note parallels between Moses and Jesus, referencing, for example, Deuteronomy 18:15 (KJV): “The LORD thy God will raise up unto thee a Prophet from the midst of thee, of thy brethren, like unto me; unto him ye shall hearken.” Recognizing Moses as a prophet significantly impacts how we read Genesis.

John will also explain that the first eleven chapters of Genesis are “primordial prophecy” with the first chapter relating to the cosmos as first created or developed, and the second through the eleventh chapters relating to the earliest ages of history. John will explain that the remainder of Genesis is “ancestral prophecy”—telling the story of inheritance.

Please join me in encouraging Dr. McKenna to finish this important book, and also join me in reading Genesis from the perspective of who Jesus is and what his plan is for all humanity. After all, as Paul says in Colossians 1:15-20, everything was created through the Son, for the Son, and to be inherited by the Son of God. In the Old Testament, we see God’s faithfulness displayed in what he was doing to prepare the world for the Incarnation of the Son of God, leading to the redemption of all humanity in and through Jesus. It is in this light that Genesis is rightly read.

Rejoicing in the goodness of our Creator who is our Redeemer,

Joseph Tkach

PS: To read more on this topic, we recommend Three Views on Creation and Evolution, and Four Views on the Historical Adam. The latter book has a helpful chapter by Denis Lamaroux on evolutionary creation. Also click here for a related Surprising God post by Gary Deddo.

[1] Quoted from Exploring Genesis: The Bible’s Ancient Traditions in Context, a free e-book from the Biblical Archaeology Society. Here is an extended quote from Hurowitz’s chapter in that book:

As recent scholarship is making clear, simplistic comparison between Enûma Eliš and the biblical tradition—as if the Bible were directly dependent on Enûma Eliš and it alone—is patently untenable.… In light of all this and more, it is impossible to accept today in a simplistic manner the claims… that the biblical authors took the Babylonian Story of Creation, that is Enûma Eliš, and simply applied it to YHWH, God of Israel. The specific parallels are fewer than originally thought and even the best ones are not entirely certain. (pp. 11-12)