Dear Brothers and Sisters,

If you’re like me, you’re amazed by cell-phone technology. At times, I have to be reminded that the device I use to take pictures, send messages, search the Internet, and play music and videos, is also a phone. Not being tethered to a cord brings a sense of freedom, but that sense disappears when the battery runs low and I must plug into a power source. Then there’s the panic that sets in upon realizing I forgot where I laid my phone! What seemed so freeing, is revealed in such moments to be less than true freedom.

“Cell-phone theology”

I share this cell-phone illustration to remind us how easy it is to misconstrue the nature of true freedom, settling for freedom that is not freedom at all. In thinking this through, I coined the term “cell-phone theology” to refer to a line of thinking that leads to false views of freedom. Cell-phone theology sees freedom the way someone (rather shockingly) described freedom to me: “It’s the ability to do whatever I want, whenever I desire.” That viewpoint misdefines freedom as absolute autonomy. But we’re never absolutely autonomous. Just try to stop breathing for ten minutes with no device to assist, and you’ll see what I mean.

Contingent freedom

Theologians refer to the freedom we actually have as “contingent freedom”—a freedom that, rather than absolute, is dependent (contingent) upon a number of things, one being time itself. Though time travel makes for fascinating movies, we know we can only live in the here and now, moving through time in linear fashion. We have freedom to act within time, and we can somewhat plan for and have an effect on the future, but we don’t have freedom to act apart from or control time.

What’s most important to know is that our freedom, in the ultimate sense, is completely dependent (contingent) upon God who created and now sustains time. Our freedom, being contingent, is dependent upon on what God has done, is doing, and will yet do within his good, yet fallen creation. To imagine life in isolation from God is not only a mistake, but a deception that leads to all sorts of slavery, particularly of the moral, spiritual and relational kind.

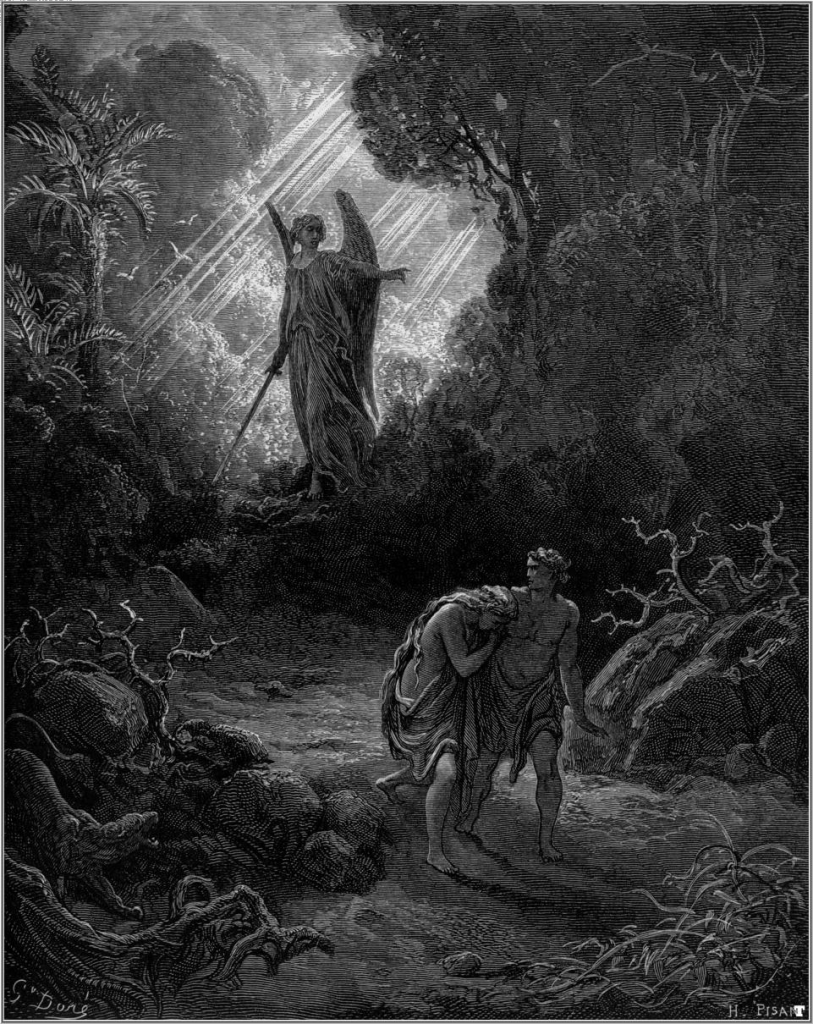

(public domain via Wikimedia Commons)

Grace and freedom

In its fallen state, humanity, to one degree or another, is in bondage—bondage to death, temptation, unchosen suffering, unjust circumstances, and to our past. Conversely, true freedom leads to life and harmonious relationships. It comes as a gift from God, extended to us by and in Jesus, through the Holy Spirit. This grace is received as we live out a deliberate relationship with God in faith (trust/belief), hope and love—for God and for his ways. Understanding this connection between God, grace and true freedom helps protect us from the bad doctrine and practice of a “cell-phone theology.”

Tethered to God

True freedom comes from acknowledging that we truly are tethered to God, our creator and redeemer, so that we might live in relation to him whether we acknowledge him or not. Think about it—existence itself is God’s gift. If God forgot us, even for a nano-second, we’d cease to exist. God alone has life in himself and we are all upheld in our existence by his grace of creation (Hebrews 1:1-3).

Some might not like my use of the word “tethered” (bound), seeing it as something contrary to grace and thus quite negative, as if we are bound to God against our will. But understand this: by grace, and for love, God has bound himself to us through Christ so that we can experience the true freedom that is ours being tethered, through Christ, to him. “For freedom Christ has set us free,” is how Paul puts it in Galatians 5:1. By the grace of God, we are bound to a relationship that involves an exchange of gifts: God freely gives us freedom, and we freely receive it as we freely give (surrender) ourselves to him. True freedom thus is about living in a worship relationship with the ever-gracious God of love.

The fruit of true freedom

The better we understand true freedom, the more we will experience God’s peace, joy, love, forgiveness, renewal—his grace in its many forms. When we live in correspondence to our freedom in Christ, we are set free to be truly human as God created us to be as his children and partners. True freedom is based on our receiving his freedom in our relationship with God and expressing it in our relationships with one another.

When people think they are free to misuse their life in one way or another, they typically are not thinking of how their actions affect others—how they hurt parents, children, a spouse, their communities or even countries. Instead of thinking about the purpose and direction of human life, and about how their attitudes and behaviors affect others, they are focused on the self and some personal, typically empty, gain.

Some say being free is about rugged individualism. But more often than not, rugged individualism is just another form of slavery to sin (see Galatians 5:1). In contrast, God has set us free for real participation in what he is accomplishing for all humanity. That participation leads to thankful obedience, an obedience moved by faith, resulting in great joy—a joy both in the here and now, and forever in eternity. Don’t forget that Jesus described the fullness of God’s kingdom as a wedding feast—a joyful celebration with great abundance.

(public domain via Wikimedia Commons)

Freedom for real relationships

Because we humans are “tethered” together through our shared history within time and space, being truly free is not about being able to choose, without constraint, between various alternatives. The freedom God gives us is not about standing aloof from others. A Christian aphorism applies here: “True freedom is not freedom from, but freedom for.” True freedom is not freedom to be detached from others, but freedom to understand that we are interconnected in relationship and then to live into that truth. Said another way, true freedom is not realized in solitary detachment from people, but in communion with them. As followers of Jesus, we have been freed to live in this fallen world with people who know of the hope we have in the glorious future that is ours through God’s promise, and also with those who do not yet realize that hope (see Galatians 5:13 and Romans 8:1-2).

There is an obvious difference between humanity’s typical view of freedom (focused on self) and God’s view of freedom (focused on living in our true humanity, received daily as a gift from him). The life of true freedom involves dying to our self-centeredness, and living instead in a way that is centered in the worship of God, lived out towards others through an obedience that comes from faith in God and all that he has accomplished and still promises to us.

Free within God’s freedom

Theologian Karl Barth reminds us that God’s freedom takes precedence over human-centered expressions of freedom. In Church Dogmatics, he wrote this: “In this positive freedom of his, God is also unlimited, unrestricted and unconditioned from without” (CD II/p. 301). Barth’s point is that God’s freedom, rather than being limited by something outside himself, is grounded in his own being. His freedom is not conditioned—God is free to be true to himself, to his own nature and character, and nothing can prevent him from being faithful to his good, just, holy and blessed name. This stands in marked contrast with false notions of divine freedom that involve projecting our own views or fears on God, seeing him as arbitrary, capricious and thus completely unlike the nature and character we find in Jesus. God has a certain nature and character, and his freedom is to be true to that nature and character as revealed in Jesus Christ.

God in his freedom is never compulsive, erratic, unfaithful, or tyrannical. Instead he is always faithful to who he is as the Triune God of love. We should therefore not imagine that our human freedom (which is contingent upon God’s freedom), is about acting on our whims, impulses, and arbitrary or disordered desires, unaccountable to anyone or anything. True human freedom depends on knowing God and his sovereign freedom, which makes it possible for his grace to be unconditional, unforced, and thus given freely to the undeserving like you and me.

Freely given, freely received

God has solely determined and established the blessing of his grace upon us in order for us to experience true freedom. Further, while his freedom is not dependent on anything (our response or behavior included), we experience that freedom when or as we respond to Christ in repentance with faith, hope and love. Our freedom is a gift freely given and so to be freely received as we are moved and set free by the Holy Spirit who ministers on the basis of the completed work of Jesus Christ. Thus we experience freedom because Jesus, by his Word and Spirit, has set us free (John 8:36)—first in relationship to him, and then to live out that freedom in community with other people.

As we respond to Christ, we find increasing freedom to live untethered by the whims of this world’s ever-changing culture with its capricious demands and arbitrary conditions. In freedom, we live in joyful proclamation that the reign (kingdom) of God currently exists, all the while expectantly awaiting its coming fullness. As we participate here and now in what God is doing, we are sent into the world to make a difference, helping others know and experience the true human freedom that is found in relationship to God as Lord and Savior. Oh, and as we go, let’s not forget to take our cell-phones! But remember, your phone (as amazing as it is) is not your freedom, though, perhaps, it will now remind you of what true freedom actually is.

Living in the wonderful freedom given us by God our creator, reconciler and redeemer,

Joseph Tkach

As I read this essay, I began to realize that the discussion was not about the essence and nature of freedom but about the object of freedom or the way that freedom is used. Either a Calvinist or Arminian could have agreed with this essay about the outcome of freedom even though their definitions of freedom are starkly different. I believe that GCI falls into the Arminian camp with regard to free will. That is, we humans have some semblance of free will and may actually choose between good and evil. Calvinists believe that free will, in the way most people understand it, does not exist. And all human choosing, for good or evil, is pre-determined and fixed by God for all time. Karl Barth, since he is in the Reformed Tradition, may in fact hold to Calvin’s all-is-predetermined view. I appreciate the essay but must confess that I read it from an Arminian or Wesleyan perspective.

Thanks for your comment David. By way of clarification, it’s important to note that GCI does not ascribe to either classic Calvinist and Armininan theolgy, but to a theology sometimes termed Incarnational Trinitarian Theology, which has a particular view of human freedom and related topics. That theology is helpfully defined in our booklet “The God Revealed in Jesus Christ.” You’ll find it at http://www.gci.org/god/revealed.