Dear Brothers and Sisters,

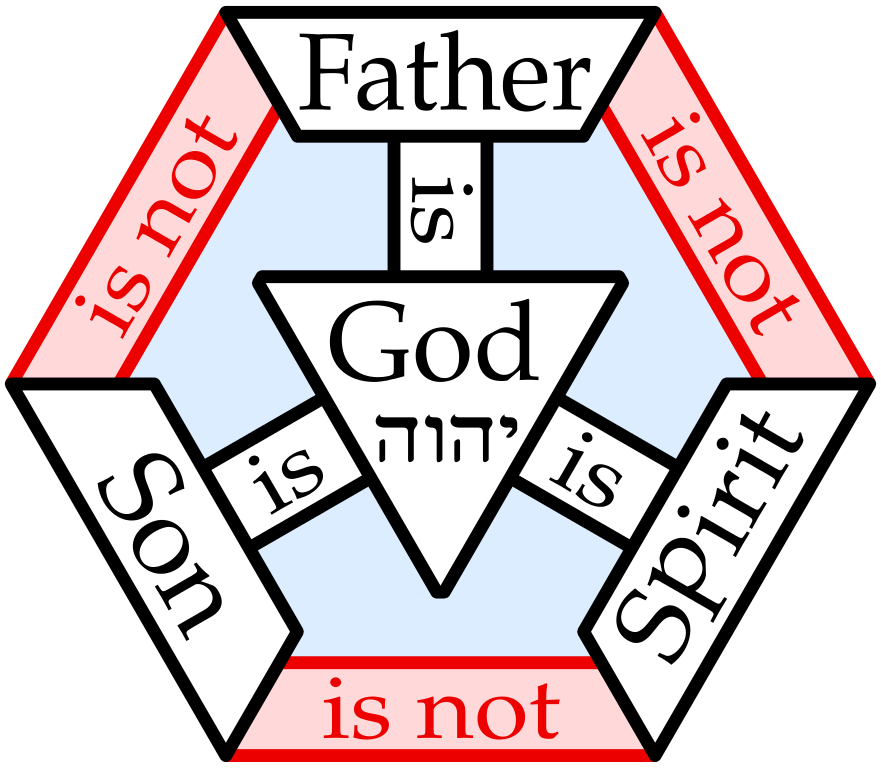

A common misunderstanding of the doctrine of the Trinity is to think that it teaches three gods (tritheism). But that is not the case. The historic, orthodox doctrine of the Trinity upholds one God (monotheism) while teaching that God is Father, Son and Holy Spirit. How can God be one and three? The answer is important to understand, not merely as a point of doctrine, but as a way for us to understand and thus relate to the one, tri-Personal God.

Three Persons, one being

To be faithful to the biblical revelation, early church teachers declared that God is one in being and three in Persons. In indicating what each of the three are, they utilized the Greek New Testament word hypostasis (ὑπόστασις), which in ancient Greek has a range of meanings: nature, substance, image, essence. This range is reflected in the various translations of Hebrews 1:3 where the Son of God is declared to be “the express image of [God’s] person [hypostasis]” (KJV translation). The NASB and ESV translate hypostasis as “nature,” the ASV as “substance,” and the NRSV and NIV as “being.” Down through the ages (including in the ancient creeds of the church), when referring to the Trinity, hypostasis was most often translated into the Latin word persona (and thus person in English—I have more to say below about the limitations of this word).

Having chosen hypostasis to refer to the three personal distinctions of God, these same teachers chose the Greek word ousia (meaning being) to refer to God’s oneness. Put together, hypostasis and ousia convey the reality revealed in Scripture that God is one in being (ousia) and three in Persons (hypostases). Thus the early church theological consensus used hypostasis (person) to refer to the three personal and eternal realities that stand forth in distinction and in relationship to each other in God’s one ousia (being).

The personal names of the three Persons that constitute the one God (the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit) were, of course, given to us by revelation. And with that revelation came the fact that there are three Persons, not two or four or an infinite number. Note that these teachers did not say that God is one being and also three beings, or one person and also three persons. How God is one is different from how God is three. Therefore, speaking precisely, we would say that there are “three real and eternal distinct Persons in the one God.”

(public domain via Wikimedia Commons)

Limitations of language

Theologians realize that the word “person” in English is not perfectly adequate to use in speaking of God’s three personal distinctions (hypostases) in relationship. This is because the way we understand persons in our creaturely experience carries with it the idea of separate individuals or different beings—an idea that does not apply in reference to God. As Athanasius noted, we must think of God theologically, not mythologically whereby we would project human, creaturely concepts onto God, as if God were a created thing.

It’s important to understand that theological language about God is necessarily analogical wherein there can only be partial overlap of meaning of the two things being compared—a prime example being the use of the word “persons” in speaking of the hypostases (the three distinct Persons) of the one God. There are points of overlapping meaning between the Persons of the Godhead and human persons that we can affirm, but there are then points that do not overlap—things that apply only to creatures and not to God and vice versa. When it comes to humans, persons remain distinct in being—they remain individuals, no matter how close (“one”) they might be relationally. But when it comes to God, the distinctions of the divine Persons (hypostases) occur within the one being (ousia) of God.

Because God is not a creature (a created being), we do not use the word Persons when speaking of God in the exact same way we use persons when speaking of human relationships, including relationships within the human family. While there are real relationships within God’s one being, those relationships are not between separate beings. The three Persons of the Trinity, through their absolutely unique relationships with one another, constitute the one being (ousia) of God in a way that is quite unlike the oneness within a human family. The relations between the Persons of God are very different from the relations that we creatures experience. In God, the relationships constitute them one in being. That is not the case for human beings. Recognizing that we are thinking analogically, we must keep in mind that the uncreated God cannot be explained in terms of the relationships within a created human family. Trying to do so would lead us into mythology and even idolatry. Recall that some pagans taught and believed that the gods are family. They also believed that the gods were sexual beings!

God is tri-personal

The relationships that occur between the three Persons within the one eternal being (ousia) of God are neither external to the Persons or to the being of God. The Father, Son and Holy Spirit can and do communicate with one another. Within the one being of God there is communion (fellowship) from all eternity, even before creation (John 17:1-26; Hebrews 1:8-9). The tri-personal God was never lonely.

When the Bible speaks of the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit, each are called God, each speak and, as Jesus tells us, each act and exhibit attributes of personhood such as knowing, loving and glorifying one another. Capitalizing the word Person is one way we indicate that the word is being used in a special way in referring to the personal distinctions within the Godhead. The word Person, understood rightly, gives us a word that emphasizes God’s personal-ness in his own being (nature), and in relationship to us as human creatures.

Grounded in the biblical revelation, early church teachers found various ways to speak of God as one in being and three in Person. Following Jesus’ teaching concerning his being “in” the Father and the Father being “in” him (John 10:38; 14:10), they spoke of the Persons “in-existing” one another (enousios in Greek). They also coined the theological term perichoresis to signify that the divine Persons “mutually indwell” or “envelope” one another, making room or space for one another. Other ways perichoresis has been translated is that the divine Persons “co-inhere” or “interpenetrate” or are “convoluted” or “involuted” with one another. The idea being conveyed is that the whole of God is present in each of the divine Persons and that all the works of the Triune God are indivisible—the three Persons always work jointly, each contributing uniquely to that work. Such a perichoretic relationship only pertains to God and to no creature or creaturely reality. God is God alone; there is none other like him.

Upholding God’s oneness, distinction and equality

The framers of the Trinity doctrine understood it to be vital to uphold simultaneously three things about God: the eternal oneness or unity of being, the eternal distinction or differentiation of the three divine Persons, and the eternal equality of divinity of the three Persons. Thus, the historic, orthodox doctrine of the Trinity preserves for us both the biblical revelation that there is but one God and no other, as well as the biblical testimony that the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit are equally divine and true God of true God. It should also be noted that the doctrine of the Trinity was never meant to explain all of what God was or how exactly God exists in a triune way. It was meant to protect the mystery of God while affirming the most faithful way to understand, as far as we can, the revelation of God in Christ and according to Scripture. It was meant to lead us to faithful worship!

Those who claim that the doctrine of the Trinity teaches three gods demonstrate a lack of understanding of the doctrine, which as I’ve already noted is monotheistic, not tritheistic. There is only one being that is God, and this one being is tri-personal, with each of the three divine Persons having full possession of the divine nature. All three Persons of the one triune God possess all the attributes of deity. British theologian Colin Gunton explained it this way:

The Father, Son and Spirit are persons because they enable each other to be truly what the other is: they neither assert at the expense of nor lose themselves in the being of the others. Being in communion is being that realizes the reality of the particular person within a structure of being together. There are not three gods, but one, because in the divine being a person is one whose being is so bound up with the being of the other two that together they make up the one God. (The Forgotten Trinity, page 56)

The three-in-one God at work

As we approach Holy Week followed by Ascension Sunday and Pentecost, keeping in mind what these days remind us of, let’s be inspired and comforted knowing that the one God who is three in Person brought about our salvation. Our Redemption was accomplished by the whole God: Father, Son and Holy Spirit. Our Triune God is actively at work in our world—in our lives! In that regard, note this from Colin Gunton:

If you were to ask him how God works in the world, what are the means by which he creates and redeems it? Irenaeus would answer: “God the Father achieves his creating and redeeming work through his two hands, the Son and the Holy Spirit.” Now this is an apparently crude image, but is actually extremely subtle. Our hands are ourselves in action; so that when we paint a picture or extend the hand of friendship to another, it is we who are doing it. According to this image, the Son and the Spirit are God in action, his personal way of being and acting in his world—God, we might say, extending the hand of salvation, of his love to his lost and perishing creation, to the extent of his only Son’s dying on the cross. Notice how close this is to the way in which we noticed John speaking in his Gospel. The Son of God, who is one with God the Father, becomes flesh and lives among us. This movement of God into the world he loves but that has made itself his enemy is the way by which we may return to him. The result of Jesus’ lifting up—his movement to cross, resurrection and ascension—is the sending of the Holy Spirit—another paraclete, or second hand of God the Father. The Spirit is the one sent by the Father at Jesus’ request to relate us to the Father through him. (The Triune God of Christian Confession, p. 10)

The next time you hear someone object to the doctrine of the Trinity, claiming it teaches three gods, I hope you’ll be able to explain to them the difference between tritheism and the actual doctrine of the Trinity. Perhaps you’ll also be able to share with them the wonderful truth of the mystery and glory of the tri-personal God revealed to us in Jesus Christ.

I wish you all a blessed Holy Week,

Joseph Tkach

PS: To learn more about the doctrine of the Trinity, I recommend that you read Delighting in the Trinity by Michael Reeves (IVP). Note also that we have a wonderful course at Grace Communion Seminary titled “The Doctrine of the Trinity.”

Thank you, Joe Tkach! This is the best explanation of our wonderful God that I have read!

I appreciate your section on The Limitations of Language. We know that God is somehow one. We also know that he is somehow three. Just because we can develop an extensive nomenclature surrounding these facts does not mean that we really understand anything about this. We are unary beings and the nature of a triune being is as inaccessible to us as the concept of timelessness. This puts us in our places and this is probably not a bad thing.

Thomas Aquinas persuasively stated that God is simple in nature and not a composite. God has no parts that have the potential to be configured into different states. God is rather always perfectly the same. I am not sure how theologians have squared this with the Trinity which is based on a composite idea.

And a word on behalf of Judaism. Followers of Judaism believe that the Trinity is a polytheistic concept – hence, a pagan concept. I do not judge Jews harshly on this. They were surrounded by pagan pantheons and had been taught strict monotheism. And the Triune nature of God had no prominence in the OT -it was rather a nuance. (The use of the word Elohim in Genesis has different interpretations lest one think that this can all be settled in one stroke with a simple exegesis.) The Jews were being asked to replace the much cherished concept of one God with the idea of a class of beings as God who were yet somehow one. Not an easy leap. My guess is that in early Christianity, pagans were much more receptive to the idea of the multiplicity of a triune God than strict Jews.

In broad strokes, a beautiful portrait of our triune God.

A beautiful vision of the love community that God has included us in.

We are bound up with God, in Christ and by the Spirit, we are bound up with one another.

We belong to God, in Christ and by the Spirit, we belong to one another.

And what can we do, but faithfully worship this beautiful God who, in Love, has given all of Himself – Father, Son, and Holy Spirit – to us, in Christ?

Thank you for this beautiful reflection for this season, Ptr Joe!

In early Judaism, as Alan F. Segal points out in his thought provoking book “The Two Powers In Heaven”, the concept of some sort of divine plurality was not unknown and indeed widespread by the first century. The concept was eventually rejected as a heresy.

Michael S. Heiser, in his provocative book “The Unseen Realm”, takes a closer look at the term Elohim while dealing with the notion of an existing divine council.

And, for those interested in exploring possible alternative views, Yoel Nathan’s “The Jewish Trinity” might provide a primer for further discussion.