Dear Brothers and Sisters,

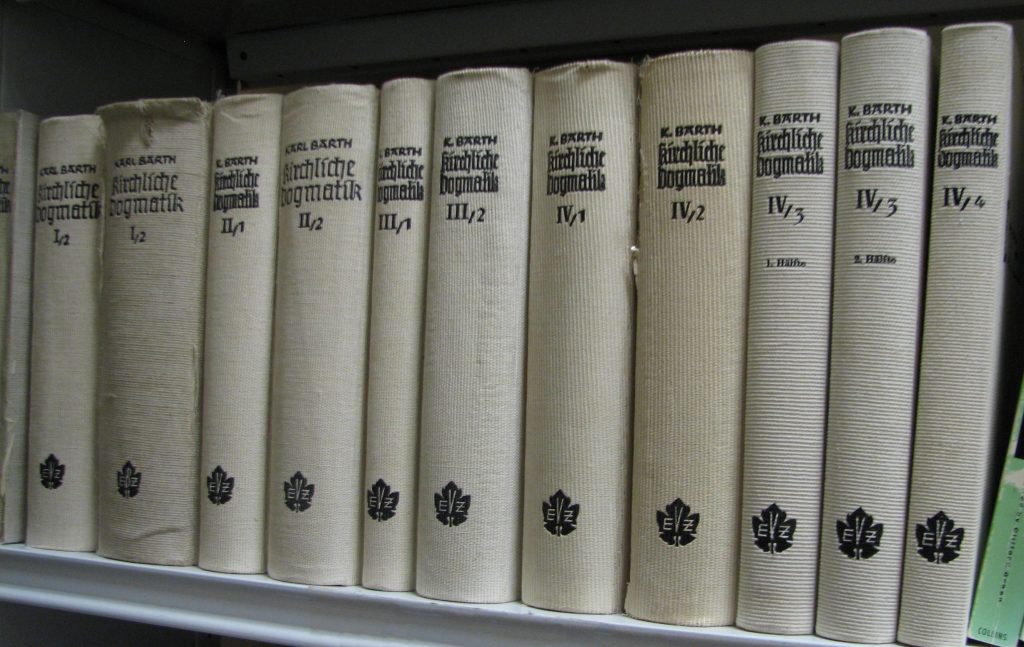

Of all the resources I’ve used in studying theology, the most complex one, no doubt, is Church Dogmatics (CD)—Karl Barth’s opus magnum, which takes up nearly two feet of my bookshelf. A few have joked with me that they are waiting for the Reader’s Digest version!

Reading CD is a rather daunting undertaking. Barth’s sentences are long, complex and densely-packed. Moreover, to understand what he says on a given topic, you must recall related concepts that he has addressed in the earlier volumes, and then recognize that he is qualifying and clarifying as he proceeds from one volume of CD to the next. As a result, Barth is often misunderstood.

Despite these challenges, I find many of Barth’s insights in CD (and in his other writings) to be truly astounding. I’m particularly fascinated with his perspective on evil, which, as I will explain in this letter, he views as a paradox. By doing so, Barth avoids the unfortunate dualistic approach to evil that is characteristic of many books on theology.

Barth’s dialectical method

In CD and his other writings, Barth approached theology knowing that God is not a creature, and thus cannot be understood in terms of creaturely experience and created realities. Nevertheless, God wanting us to know him, revealed himself to us in human form, and spoke to us with human language. But because human language has limits, speaking faithfully about God will sometimes require that we say two different (even opposing) things at the same time in order to accurately account for God’s transcendent reality. This is so because neither statement alone would be sufficient to convey the full truth. Pointing to the truth of God would, in such instances, require holding two distinct claims despite the tension between them. This approach to theology, for which Barth is well known, is called the “dialectical method.”

Examples of seemingly irreconcilable statements held together (in tension) by the dialectical method include the statements “humans are in God’s image” alongside “all humanity fell from its created state of glory.” Another pair of statements is that, in Jesus, “we are masters of all things,” yet, as fallen creatures, “we are slaves to all things.” Barth understood that there is no way to perfectly resolve these rational tensions without turning God into a creature and thus distorting the biblical witness to the God who is revealed in Jesus Christ. Therefore, Barth uses the dialectical method to uphold both statements (affirmations) despite the apparent tensions between them.

Evil—much ado about nothing

Using the dialectical method to examine the topic of evil, Barth finds that evil must be understood as both not something and not nothing. Accordingly, he refers to evil as “nothingness” (Das Nichtige in German). He goes on to describe evil as a force that threatens to corrupt and destroy God’s good creation. Nevertheless, he also sees concern about evil as (to borrow a phrase from Shakespeare) “much ado about nothing.” On the one hand, evil (nothingness) is “that which God does not will,” but on the other hand (and here comes the dialectical tension) Jesus Christ overcame evil as something that truly needed to be undone. Therefore, what Jesus overcame must have real existence of some sort, though its existence, when compared to the will of God, is a bare (shadowy, ephemeral) one, so that, in the end, evil cannot and will not exist at all.

Barth is thus proclaiming that to think biblically about evil, we must understand that because it exists in a way that is wholly in contradiction to God’s eternal, set will, and because it has been decisively conquered by Jesus, it is correctly understood only as “nothingness.” Barth is not playing word-games here—he’s saying that evil is almost nothing and can only lead to being absolutely nothing. To make his point, he must stretch human language to its limits. In doing so, he helps us understand evil, in the light of Christ, for what it actually is—“nothingness” (that which is next to nothing).

Barth explains that this nothingness is utterly distinct from both Creator and creation, representing the inexplicable work of the adversary with whom no compromise is possible. So (and stay with me now to the end of a long sentence), we are left with the nothingness being something that is all but absolutely nothing, and, for a time, this nothingness brings corruption and chaos to the good order of creation, resisting as it does the coming kingdom of God. Wait a minute—nothingness bringing corruption and chaos to something? Yes, though hard to grasp, let this statement sink in. God, who created something out of nothing (creatio ex nihilo) did not create the nothingness. Therefore, he is not the creator of evil. However, he is evil’s conqueror.

Evil (nothingness) moves the something of God’s good creation in the opposite direction to what God wills for it. Barth comments:

Any roads leading away from it (the Glory of God’s Eternity) can lead only to utter nothingness, and therefore cannot be roads at all. Since movement away from it is movement into the utter (or absolute) nothingness, there can be no such movement. (CD II.1, p. 629)

Nothingness, Barth continues, is “irrational” and thus “inexplicable” because it is “absolutely without norm or standard.” Evil cannot be explained (rationalized)—there is no good reason for it. There is no “why” to it that can be answered by giving it a good reason or purpose. If a good answer could be provided as to why evil exists, then we would have made evil far less evil and in fact a contributor to some good. We would, with such an answer, be justifying evil.

But evil has no justification. And were it justifiable, because it was needed to contribute to some greater good (i.e. if evil were somehow necessary), then there would be no need for Jesus Christ, because evil would simply justify itself as being needed to contribute to what is good. But that cannot be, for evil itself is completely unjustified—it is what ought not be, and, indeed, has no good reason to be. Evil is what Jesus Christ has overcome.

Jesus—the way out of nothingness

In understanding evil this way, Barth affirms the biblical claim that all people (sinners all) “have become the victims and servants of nothingness, sharing its nature and producing and extending it.” While we all experience evil (nothingness) in our temporal lives, the good news is that we don’t have to suffer forever since God is sovereign over eternity. God has provided a way for us out of the bonds of nothingness, and that way is Jesus Christ, whose humanity begins the new creation.

In Jesus, evil, sin and death are overcome. In Jesus, nothingness meets its reality, and so becomes absolutely nothing. God, in Christ and by the Spirit, limits and conquers the negative aspects of this nothingness that can and have threatened the significance of the existence of the world and the human race within it. Again, to borrow a phrase from Shakespeare (here words spoken by King Lear), “Nothing will come of nothing.”

In Christ, God has given an absolute and uncompromising “No!” to nothingness as an uninvited, unwanted intruder into his good creation. While God did not create nothingness (which was at work in the chaos from the beginning), he will vanquish and conquer it completely. That is a big reason the gospel is good news.

In spite of the difficulty and complexity involved in reading CD, it is rewarding to do so when persistently pursued. I illustrate this by relating a comment from my dear friend, Grace Communion Seminary Professor Dr. John McKenna. He once told me that when he read and understood Barth’s picture of redemption, for the first time in his life (through all the pain, sin and heartache of his past) he felt that God truly loved him—he no longer feared the nothingness. He said it was as if someone had laid hands upon him and healed him. I love that illustration, because I believe the true and miraculous path to our healing comes from realizing that Jesus Christ is the only means of freeing humanity from evil—from the grip of nothingness.

We are reminded daily that we live in a world of injustice, cruelty, pain and suffering—the picture of this present world presented in Scripture. However, the reality is that Jesus has promised to take all this pain and suffering away, leading to a new heaven and new earth at his return. In our modern times, the only philosophical problem of evil that could ever trouble a thinking Christian is some kind of confirmation of a total absence of sin and evil in the world. This is because, paradoxically, the presence of evil in the world proves the validity of Christianity’s claim that there is evil (things that simply ought not to be but somehow do exist), and Christianity’s affirmation that we all need to be rescued from evil but cannot do so ourselves. However, there is real hope because evil has been conquered and a time is coming when God (as he has promised) will wipe away all tears, and there shall be no more death, sorrow, crying, or pain. That which ought not be, will, in the end, not be. In short, evil has no future!

Loving Jesus and his promises,

Joseph Tkach

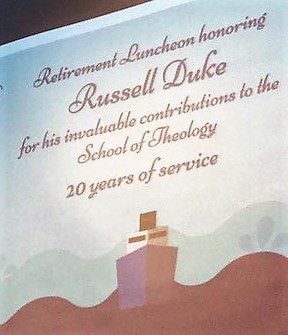

Azusa Pacific University (APU) in Azusa, CA, recently honored Dr. Russell Duke with a luncheon marking his retirement (effective May 31) from employment with APU. Russell is pictured at right, addressing the gathering.

Azusa Pacific University (APU) in Azusa, CA, recently honored Dr. Russell Duke with a luncheon marking his retirement (effective May 31) from employment with APU. Russell is pictured at right, addressing the gathering.