Dear Brothers and Sisters,

Knowing that God forbids the worship of any created thing, the apostle Paul was deeply distressed seeing the idolatry on display in Athens (Acts 17:16). But rather than fleeing the city, Paul spent considerable time in its marketplace (the Agora), “preaching the good news about Jesus and the resurrection” (Acts 17:18). His goal was to proclaim the true, living God who is Lord over all creation and victor over death, creation’s seemingly undefeatable enemy.

Some who heard Paul preach in the Agora invited him to present his ideas at the nearby Areopagus (Mars Hill). It was there that Paul spoke these now-familiar words concerning God: “For in him we live and move and have our being” (Acts 17:28). In our day, some mistakenly interpret “in him” as meaning that all people are somehow inside God. But taking Paul’s statement that way is mistaken in two ways:

First, God is not subject to the physics of creation—he has neither an “inside” nor an “outside” like an object extended in space. Distinct from all he created, God is “wholly other,” a phrase used in theology to describe the absolute difference in being between God and everything else. God exists in a completely different way than all other things that have existence. As God told Moses, he is the great “I am that I am.” God’s being can neither be known nor explained by anything else, for God is incomparable—everything else that exists is created and, at one time, did not exist.

Second, in his statement at the Areopagus, Paul was quoting non-Christian poets known to his audience. “In him we live and move and have our being” quotes Epimenides the Cretan. Paul then went on to say that “for we are his [God’s] offspring,” which quotes Aratus the Cilician. In sharing these quotes, rather than affirming what the poets wrote about their god (called the “unknown God” by the Athenians, Acts 17:23), Paul was offering a simple basis to relate to the true God revealed in Jesus Christ. According to Paul, the one, true God is near enough to all people that he may be found and thus known (Acts 17:27). Paul then called on his audience to repent—to turn from their idolatry to the true God (Acts 17:29-31) who, though transcendent over creation, makes himself able to be interacted with. Indeed, the so-called “unknown” God can be known intimately, for he has both the will and the power to reveal himself to us.

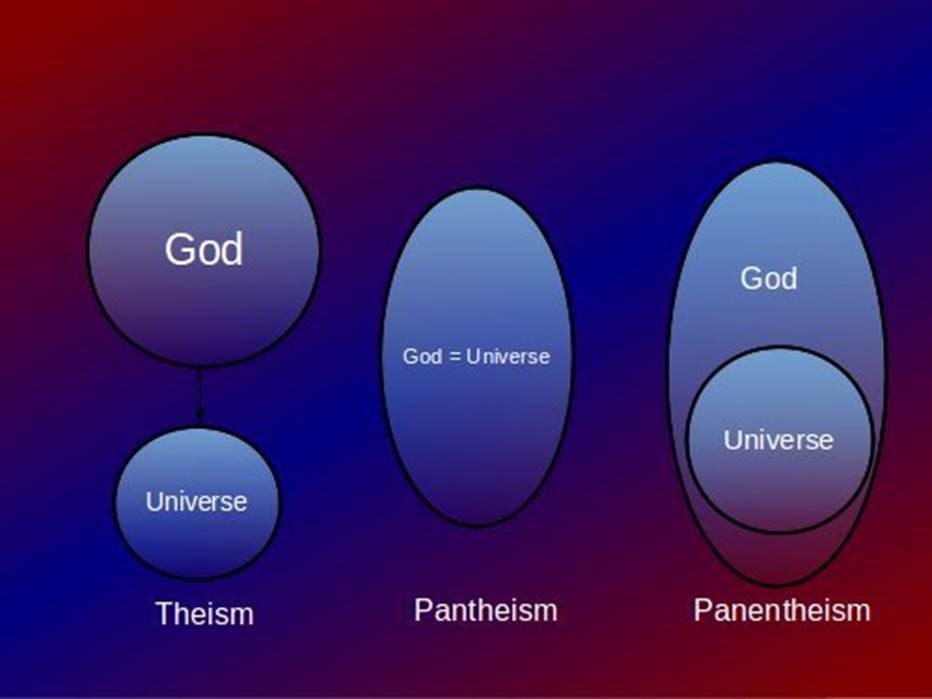

Contrary to the claims of some in our day, Paul taught neither pantheism nor panentheism. As shown in the diagram below, pantheism teaches that God and nature are one and the same, and thus cannot be distinguished. Panentheism, which is closely akin to pantheism, teaches that though there is more to God than creation, all of creation is part of God’s being (and thus divine), or somehow is an extension of God’s being. Paul’s teaching concerning the nature of God (theism) was markedly different than either of these non-biblical teachings. Let’s now take a closer look at panentheism.

Panentheism’s history and flaws

Panentheism arose out of philosophical speculations that regarded good and evil as eternal and equal—a cosmological dualism. Added to this was the idea that good and evil are eternally in competition. Around 500 B.C., Heraclitus’s “flux philosophy” asserted that the world is a constantly changing process. In following years, Plato (428-348 B.C.) often referred to the Demiurge, an entity that fashioned and shaped the material world, struggling to try to form the cosmos out of chaos.

These pagan Greek beliefs gave rise to the dualistic claims that the transcendent source of material things (god) has two poles in its being: good and evil (with the material aspect prone to evil). This understanding is flawed because God cannot be pure goodness (nor the standard of goodness) if ontologically he also contains evil. What “side” of God is called good and what “side” is called evil would be arbitrary, since they both would be ultimate, even if in their opposition. Though there are various panentheistic views in our day, they all teach that God and the world are essentially interdependent, even if the world does not contribute anything to God’s essence.

Many theologians (ancient and modern) teach that these features of panentheism are in clear conflict with Christianity and its Hebrew roots. We can identify this conflict on several levels. Here are five:

- The God revealed in Scripture does not contain within his being a polar mixture of good and evil. He cannot be joined in being with a creation that has evil within it—evil that must be eradicated.

- God is neither dependent upon nor is he interdependent with creation. That would negate God’s sovereignty over his creation and thereby eliminate the guarantee of him being its Redeemer and Savior.

- Panentheism teaches that God created the universe from pre-existing material (ex materia) that has always existed along with God since it is joined to his eternal being. Such a claim denies a foundational Christian belief in creation ex nihilo—that God created everything from nothing. Scripture teaches that creation is not eternal like God is—it is not self-existent.

- Panentheism often claims that God’s actual existence and nature are in the process of changing (though God’s potential—all that he could become—does not change). Theologian Norman Geisler addresses this false idea in the Baker Encyclopedia of Christian Apologetics: “Panentheists think of God as a finite, changing, director of world affairs who works in cooperation with the world in order to achieve greater perfection in his nature…. They believe the world is God’s body” (p. 576). As Geisler notes, one fatal flaw of panentheism is that it implies that God is not a maximally great being worthy of worship. A panentheistic “god” is on the way, and how far this god actually progresses depends upon what takes place in the history of the world, since the world is an extension of this god’s being.

- The notion inherent to panentheism that God has evil existing within himself, conflicts with the Christian view of God as holy, pure, good, just, immutable, opposed to evil, perfectly loving, true and righteous. As the apostle John declared: “This is the message we have heard from him and proclaim to you, that God is light, and in him is no darkness at all” (1 John 1:5). The apostle James put it this way: “When tempted, no one should say, “God is tempting me.” For God cannot be tempted by evil, nor does he tempt anyone…. Every good and perfect gift is from above, coming down from the Father of the heavenly lights, who does not change like shifting shadows” (James 1:13, 17).

A Christian panentheism?

Some who self-identify as Christians use the word panentheism in describing their beliefs. Perhaps they do not realize the serious problems in doing so, since the word and concept, as nearly universally used (in the ways noted above), contradict the historic, orthodox Christian faith.

That being said, I want to note that Eastern Orthodox theologians sometimes use the word panentheism to describe the personal activity of God in the world. It is important to note, however, that in doing so, they unreservedly affirm creation out of nothing (ex nihilo) and use the term panentheism to mean God (theos) can act everywhere (pan) in (en) the world that he created. Eastern Orthodoxy, which correctly teaches that the universe is contingent, distinct from God, and wholly dependent on God for its existence, also teaches that the universe is not a part of God’s essence. Instead, it teaches that the universe emerges from God’s divine energies, which emanate from God, permeating the universe and maintaining God’s presence within it, with no fusion or confusion of being with the universe.

One Orthodox writer expressed this idea by hyphenating the word as pan-entheism, stressing all things (pan) dwelling in God (entheism), rather than panen-theism, stressing God dwelling in all things. The latter conveys the mistaken idea that all things are a part of God, whereas the former conveys the correct idea that God is present to and upholds all things (though God is not the sum of all things). This is how Eastern Orthodoxy makes use of the term panentheism, though their usage with its myriad Christian qualifications hardly resembles the word in its more common usage.

As Christians, we know and teach that in Christ we “live and move and have our being,” However, that does not mean that we are somehow inside of God, or that our beings are somehow fused with God’s being. Being “in God” is about being in relationship with him—in communion with him, in sync with him, realizing that all we are is because of him, that all we do is for him, and our identity is in him. That is our hope—this is our reality.

If you have not yet read Gary Deddo’s article, “Avoiding the Pitfalls of Panentheism” published in an earlier issue of GCI Weekly Update, I highly recommend you do so (click here to read it online). Gary identifies at least a dozen ways panentheism contradicts classic Christian doctrine.

Celebrating that God is wholly other and unique,

Joseph Tkach

PS: I am deeply saddened by the mass shooting that occurred recently in Las Vegas. Let us unite in prayer for those who lost loved ones, and for the wounded who continue to fight to survive. Let us also pray for the Las Vegas civic leaders, churches and citizens as they join together in recovering from a terrible, senseless tragedy.

I readily admit that certain trends in Christian circles make me very cautious and skeptical as these developments often unfortunately take on characteristics and elements that could well be associated with New Age concepts. More specifically, while not being per se against the “spiritual formation movement”, it seems to me that this “practice” focuses all too frequently, and sometimes quite subtly, on the self rather than on God. Kind of reminds me of Gnosticism and/or of the popular ideas in the field of psychology involving various forms of “self actualization”. Orthodox theology can be rather mystic and contemplative. As always, we must learn to exercise discernment. Even “fruits” that look healthy on the outside may turn out to be upon closer inspection rotten in the core.