Dear Brothers and Sisters,

Through his incessant trashing of Christian beliefs, German philosopher Frederick Nietzsche (d. 1900) became known as the “ultimate atheist.” He claimed that the Christian narrative, particularly with its emphasis on love, is the byproduct of decadence, corruption and vengeance. Rather than admitting the existence of God, his now famous statement, “God is dead,” proclaimed the death of the very idea of God. His goal was to see traditional Christian belief (he called it “old, dead belief”) replaced with something radically new. He said that upon “hearing the news that ‘the old god is dead,’ we philosophers and free spirits feel illuminated by a new dawn.” For Nietzsche, the new dawn was a society of “joyous wisdom”—a place free of repressive beliefs that set narrow limits on people’s joy.

How should we relate with atheists?

Nietzsche’s philosophy has motivated many people to embrace atheism. Even some Christians endorse his teachings, thinking they condemn a form of Christianity that operates as though God were dead. What they fail to realize is that Nietzsche found the idea of any god absurd and any form of faith foolish and hurtful. His philosophy is thus contrary to biblical Christianity, though that does not mean we mock him or any other atheists. Our calling is to help people (atheists included) understand that God is for them. We fulfill this calling by living in a way that exemplifies for others a joy-filled relationship with God—or as we say in GCI, we live and share the gospel.

You’ve likely seen posters or bumper stickers that mock Nietzsche (like the one above). What these fail to account for is that during the year before he lost his sanity, Nietzsche wrote several poems that seem to indicate a change in his perspective on God. Here is one of those poems:

No, come back, with all your torments!

All the streams of my tears run their course to you.

And the last frame of my heart – it burns up to you!

Oh come back, my unknown God! My pain! My last happiness.

Misunderstanding God and the Christian life

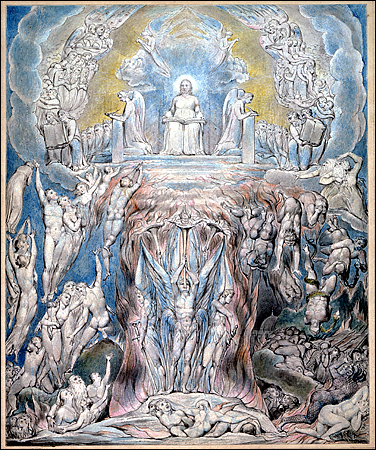

It seems there is no end to the false representations of God that fuel the fires of atheism. God is falsely represented as vindictive, restrictive and punitive, rather than the God of love, mercy and justice revealed in Jesus Christ, the Savior who invites us to abandon the life that leads to death to embrace the new life of faith in him. Rather than one of condemnation and repression, the Christian life is one of joy-filled participation in the ongoing ministry of Jesus, the one who said he came not to condemn the world, but to save it (John 3:16-17).

To understand God and the Christian life rightly, it’s important to understand the distinction between God’s judgments and condemnation. God makes judgments not because he is against us, but because he is for us. Through his judgments, God is pointing out the ways that lead to eternal death—ways that block fellowship with him by which we receive, by grace, his many benefits and blessings. Because God is love, in judgment he stands against all that is against us, his beloved.

While human judgment is often meant to condemn, God’s judgments show us what leads to life compared to what leads to death. His judgments enable us to avoid the condemnation due to sin or evil. God sent his Son into the world to conquer the power of sin and to rescue us from its bondage and its ultimate result, eternal death. The triune God wants us to know the only real freedom there is: knowing Jesus Christ, the Living Truth who sets us free.

Contrary to Nietzsche’s misconceptions, the Christian life is not a narrow one of repression. Instead, it is a joy-filled life of living in and with Christ, by the Spirit. It involves participating with Jesus in what he is doing. I personally like the explanation that some give using a sports analogy: Christianity is not a spectator sport. Of course, some even misinterpret this to push people toward working for their salvation. There is a big difference between working for salvation (which puts the emphasis on us) and participating with Jesus, who is our salvation (which puts the emphasis on him).

Christian atheists?

Perhaps you’ve heard the term “Christian atheist.” It speaks of those who profess belief in God but, not knowing much about him, live as though God does not exist. A sincere believer can become a Christian atheist by ceasing to be a fully-devoted follower of Jesus. They can become so consumed with activity (even activity labeled as Christian) that they become part-time followers of Jesus—more focused on activity than on Christ.

Then there are those who, believing that God loves them and that they have a relationship with God, see no need to participate in the life of the church. In holding that view, they (perhaps unwittingly) reject being incorporated into and living as a member of the body of Christ. While they may trust God for occasional guidance, they don’t want God taking charge of their lives. Like the poster at right, they want God to be their co-pilot. Some even prefer that God be their flight attendant—merely providing what is asked for from time to time. But God is no co-pilot, and certainly no flight attendant. God is our pilot—he gives the directions that lead to real life. In fact, he is the life, the truth and the way.

Participate with God in the fellowship of the church

God calls believers to join with him in what he is doing to bring many sons and daughters to glory (Heb. 2:10). He invites us to participate in his mission to the world by living and sharing the gospel. We do that together as members of Christ’s body, the church (ministry is a team sport!). No one person has all the Spirit’s giftings, so all are needed. Within the fellowship of the church, we give and receive from one another—we build each other up and strengthen one another. As the author of Hebrews admonishes, we do not neglect coming together in community (Heb. 10:25), we join with others in doing the work to which God has called us as a community of believers.

Enjoying real, eternal life with Christ

Jesus, the Son of God incarnate, sacrificed his life that we might have “real and eternal life” (John 10:9-11, The Message). This life is not about guaranteed riches or good health. It’s not about always being free of pain. Instead, it’s about knowing that God loves us, and having forgiven and accepted us, has adopted us as his child. Rather than a restricted, narrow life, it is a life filled with hope, joy and assurance. It is a life of becoming what God intends for us to become, through the Spirit, as followers of Jesus Christ.

God, having judged evil, condemned it at the cross of Christ. Therefore evil has no future, and all history has been set on a new direction in which we, by faith, can share. God has not allowed anything to happen that he cannot redeem. Indeed, “every tear will be wiped away,” for God, in Christ and by the Holy Spirit, is “making everything new” (Rev. 21:4-5).

That, dear friends, is the gospel, and it is very good news! It tells us that God does not give up on anyone, even when they give up on him. As the apostle John explains, God is love (1 John 4:8)—love is the nature of his being. God never stops loving us, for to do so, he would be contradicting the essence of who he is. Therefore we can be encouraged to know that God’s love includes everyone who has ever lived or will yet live, and that includes Frederick Nietzsche and all other atheists. We can hope that as God’s love reached out to Nietzsche, near the end of his life he experienced the repentance and faith God intends and provides for all. Indeed, “everyone who calls on the name of the Lord will be saved” (Rom. 10:13).

Loving that God never stops loving any of us,

Joseph Tkach

Perhaps you remember

Perhaps you remember