Dear Brothers and Sisters,

People turn away from belief in God for many reasons, but one of the most prevalent is “the problem of evil”—what theologian Peter Kreeft calls “the greatest test of faith, the greatest temptation to unbelief.”

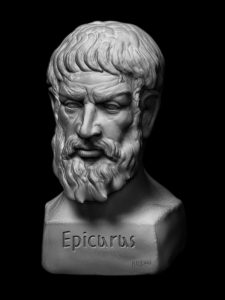

Agnostics and atheists often use the problem of evil as their go-to argument to either doubt or deny the existence of God. Their claim is that the co-existence of evil and God is either unlikely (agnostics) or impossible (atheists). This line of reasoning goes back as far as the Greek philosopher Epicurus (c. 300 BC), who made the following statement that, in the late 1700s, was picked up and popularized by Scottish philosopher David Hume:

Is God willing to prevent evil, but not able? Then he is not omnipotent. Is he able but not willing? Then he is malevolent. Is he both able and willing? Then whence cometh evil? Is he neither able nor willing? Then why call him God?

(public domain)

(public domain)

Epicurus, and Hume after him, were painting a less-than-godly picture of God. I don’t have room here for a comprehensive reply (what theologians call a theodicy), but I do want to point out that this line of reasoning doesn’t come close to being a knock-down argument against the existence of a good God. As pointed out by many Christian apologists, the existence of evil in the world, rather than disproving God’s existence, proves just the opposite, as I’ll now explain.

Evil necessitates goodness

The observation that evil is an objective feature within our world is a double-edged sword that cuts agnostics and atheists much more deeply than it cuts theists. To argue that the presence of evil in the world disproves the existence of God, one must affirm that evil actually exists. It follows that there must be an absolute standard of goodness that defines evil as being evil. One simply cannot form a logical concept of evil without appealing to an ultimate standard of goodness. This leads to a huge dilemma in that it raises the question of the source of this standard. Said another way, if evil is the opposite of good, how do we determine what is good? And where does that understanding come from?

We are told in the book of Genesis that the world was created good, not evil. Yet, Genesis also tells of the fall of humankind—a fall caused by evil and resulting in evil. Because of evil, this world is not the best it can be. Thus the problem of evil points to a departure from the way things ought to be. If things are not the way they ought to be, then there must be a way they should be. If there is a way they should be, there must be a transcendent design, plan, and purpose for the way it should be, and if so, there must be a transcendent being (God) who authored that plan. If there is no God, then there is no way things ought to be, and hence there is no evil. All this might sound a bit confusing, but it’s not. It’s a carefully constructed line of logic.

Injustice necessitates justice

C.S. Lewis championed this logic. In Mere Christianity, he shares how he had been an atheist, due largely to the presence of evil, cruelty and injustice in the world. However, the more he pondered his atheism, the more he saw clearly that the concept of injustice was dependent on an absolute concept of justice. Justice necessitates a just Someone who is beyond humanity and has the authority to shape created reality and promulgate the rules that define justice within that reality. Moreover, he came to see that the origin of evil is not God the Creator, but the creatures, who falling into the temptation to distrust God, chose to sin.

Lewis came to see that if humans were the source of what is good and evil, they could not be objective since they were subject to change. Further, he deduced that one group of humans may pronounce verdicts on others as to what is right and wrong, but then the other group would impose their own version of right and wrong. Then the question would have to be asked as to what authority stands behind these competing versions of right and wrong? Where is the objective standard when what is unacceptable in one culture is deemed permissible in another? We see this dilemma at work throughout the world, often (unfortunately) in the name of religion and other ideologies.

The bottom line is this: if no ultimate creator and moral lawgiver exists, there can be no objective standard of goodness. And if there is no objective standard of goodness, how can anyone discover this to be the case? Lewis made this point with an illustration: “If there were no light in the universe, and therefore no creatures with eyes, we should never have known that it was dark. Dark would be a word without meaning.”

Our personal and good God overcomes evil

Only if there is a personal and good God who is opposed to evil does it make sense to lodge a complaint against evil or make an appeal to have something done about it. Were there no such God, there would be no one to appeal to and no basis for thinking that what we call good and evil is anything more than our personal preference (which we would label “good”) being in conflict with someone else’s personal preference (which we would label “evil”). In that case, there would be no such thing as objective evil, and thus nothing really to complain about, and certainly no one to complain to. Things would simply be the way they are, call them what you like.

Only by believing in a personal and good God do we have grounds to object to evil, and Someone to appeal to for its eradication. Having the conviction that there is a real problem of evil and hoping that evil will, one day, be undone and everything put right, serves as a good reason to believe that a personal and good God exists.

Though evil lingers, God is with us and we have hope

Evil exists—the evidence is all over the news. We’ve experienced evil and know its destruction. But we also know that God did not leave us in our fallen state. As I pointed out in a Weekly Update article a couple of weeks ago, God was not surprised by the fall. He did not need to revert to a plan B, for he had already set in motion his one plan to overcome evil, and that plan is Jesus Christ and the atonement. Through Christ, God overcame evil by his authentic love, and he had his plan in place from the foundation of the world. In the cross and resurrection of Jesus we see that evil will not have the last word. Evil has no future because of what God, in Christ, has done.

Do you yearn for a God who confirms that there is evil, who graciously takes responsibility for it, who is committed to doing something about it, and who will make everything right in the end? If so, I’ve got good news for you—that’s exactly who the God revealed in Jesus Christ is.

Though we live in a time Paul calls “the present evil age” (Galatians 1:4), God has not abandoned you, nor left you without hope. [1] God reassures us all that he is with us, having broken through to us in the here-and-now, and therefore giving us the blessing of experiencing the “firstfruits” (Romans 8:23) of the “age to come” (Luke 18:30)—a “deposit” (Ephesians 1:13-14) of the goodness of God’s rule and reign as it will be in the fullness of his kingdom.

Today, by God’s grace, we embody through our life together in the church, the signs of God’s kingdom. The triune God, living in us, enables us to taste, even now, the relationships he originally designed for us to enjoy in communion with God and one another—true life never-ending and without evil. Yes, we have our struggles on this side of glory, yet we are comforted knowing that God is with us—his love lives in us at all times through Christ—by his Word and Spirit. As Scripture assures, “The one who is in you is greater than the one who is in the world” (1 John 4:4).

Grateful to our good God who has overcome evil,

Joseph Tkach

[1] For another Weekly Update letter on the hope that is ours despite the presence of evil in the world, click here.